Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 3A, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

…………………

The preceding tape related last how my father had been rounded up together with others in what I believe was the Vél d’Hiver [ed: Vélodrome d’Hiver;] or perhaps the Stade de Colombes [ed: Stade Yves-du-Manoir in Colombes] (I don’t know which,) and my mother had received from the Austrian Socialist Committee permission to bring him a blanket. That was a mistake that the Committee had made because they could have obtained his release and that fact plays a role later on. At any rate my father was sent to one of the camps in the Finistère. And there was another infamous one called Gurs, from which people were later delivered to Nazi concentration camps, however he went to the Finistère and there, after only a few days, the camp was overrun by the German army. A company, under the leadership of a captain, took the camp. He arranged the — he ordered the prisoners to divide into two groups. One group were to be Germans who were to be liberated – Germans and Austrians. And the other group were Jewish refugees. Then he held a speech for the Jewish refugees and told them, “I am a soldier in the German Wehrmacht. I am not a butcher. I do know that in about two hours the SS will be here, and I am not going to play any part in delivering you to them. So, take off and run as far as you can.” Well, the people didn’t need to be told twice. They went to the wall – except my father, who found it below his dignity to run or to climb over a wall. But, at any rate, some fellow prisoners just took him by the arm and took him along and he eventually made his way back to Paris.

My parents lived somehow with the help of some organizations. You know, these were the early days of German occupation at which time the Germans made a big effort to impress the French with their correctness and politeness. This period didn’t last very long but, in the beginning, there were still such things as refugee organizations, and the big roundup of the Jews had not yet started. The famous Kristallnacht came much later. Dicky [ed: Dicky was able to relocate to Paris a few months after Viggi and Viktor] behaved marvelously at the time. She went to see my parents and behaved as if she had been their daughter.

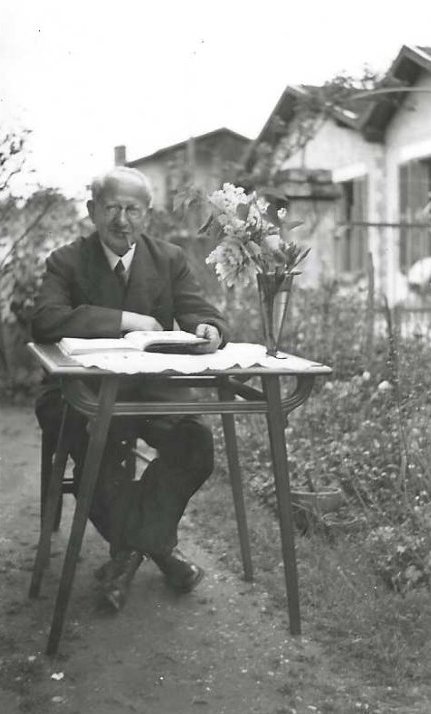

Well, on New Year’s Eve of 1939 my mother died and after that my father was, understandably felt pretty lost and, after a few weeks, he decided that he wanted to get to the unoccupied zone. You know, France was divided at that time into an occupied zone in the north, and south of the Loire was the Vichy regime and that was the zone libre. Well, in order to accomplish this, he needed a pass and he marched into an office of the Feld gendarmerie or perhaps it was an office of the outfit that was in charge that did something like being the mayor of — military mayor, the Stadtkommendatur, (and that office, incidentally, was in the Banque d’Escompte,) and he walked in there, found the appropriate office, marched in and told the man, “Ich bin der Doktor Gruder aus Wien. Ich bin ein Jude. Ich bin ein Sozialist. Ich bin seit eh und je Ihr Gegner gewesen. Sie haben für mich keine Gebrauch und ich für Sie nicht. Ich wünsche einen Pass, um in die freie Zone zu gehen, nach Montauban, wo ich auf das Visum warten will, das mein Sohn mir aus Amerika schicken wird.” [“I am Doctor Gruder from Vienna. I am a Jew. I am a Socialist. I have been your opponent since forever. You have no use for me and I have no use for you. I want a passport to go to the free zone, to Montauban, where I want to wait for the visa that my son will send me from America.”] The man just stared at my father, didn’t say a word. Let me add that my father looked rather impressive and, without any comment, he gave him the pass. That whole behavior was typical for my father. Don’t believe for a moment that this was a trick or chutzpah. My father was a man totally without guile and what he did there was his natural behavior. In this case, it miraculously worked.

He went to Montauban, where many refugees were assembled because the mayor of that town was a very decent chap. (Incidentally, the Frieds [ed: the parents of a childhood friend of Monica’s; see Letter 11 “Musings on Art”] lived in Montauban at the same time, but the Frieds and my father didn’t know each other.) And there he, at that time, was still able to write me letters because we were not yet at war, and I sent him sporadically checks of small amounts that I was able to scrape together and, with that and the help of some committees, he was able to survive, not very well. He was a very sick man, but he not once seemed to have lost the certainty that I would get him a visum to the United States.

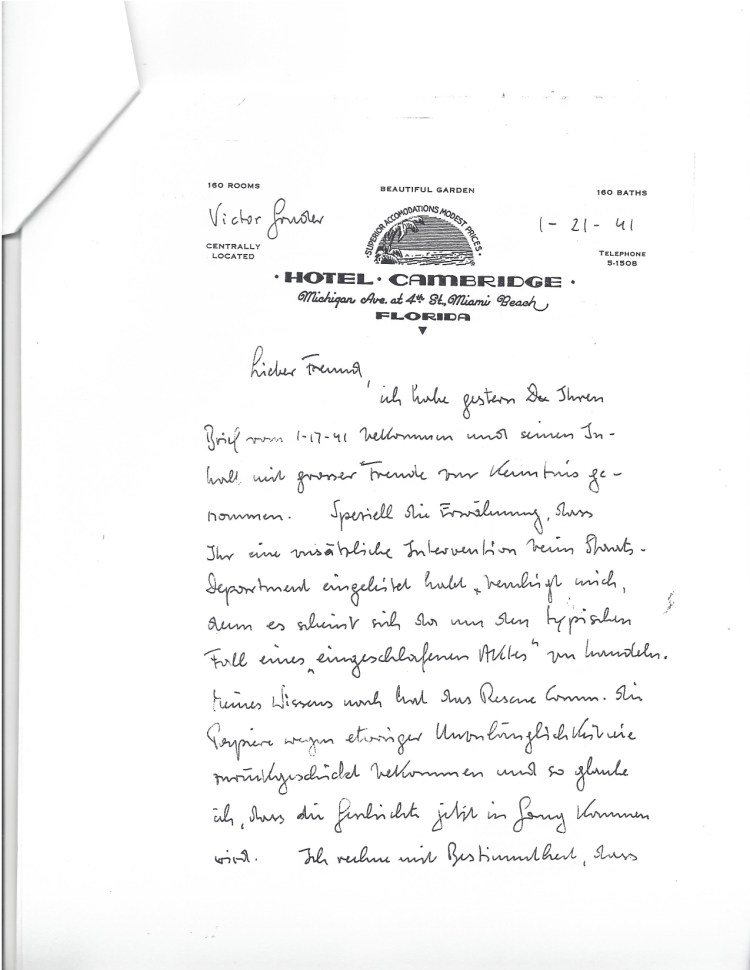

Well, once again he was correct; he was right in that expectation. It took two years, during which I had no hope of getting the visum, but in 1941, before we entered the war (we, the United States, entered the war) there was a committee created by Mrs. Roosevelt. It had a name something like Committee for the Rescue of Central European Intellectuals Threatened by an Immediate Danger, or some such thing. [ed: perhaps a conflation of the Emergency Rescue Committee and the Committee to Save the Jews of Europe or the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars.] And she arranged to get a block of visums outside the quota and my father was among those who got a visum.

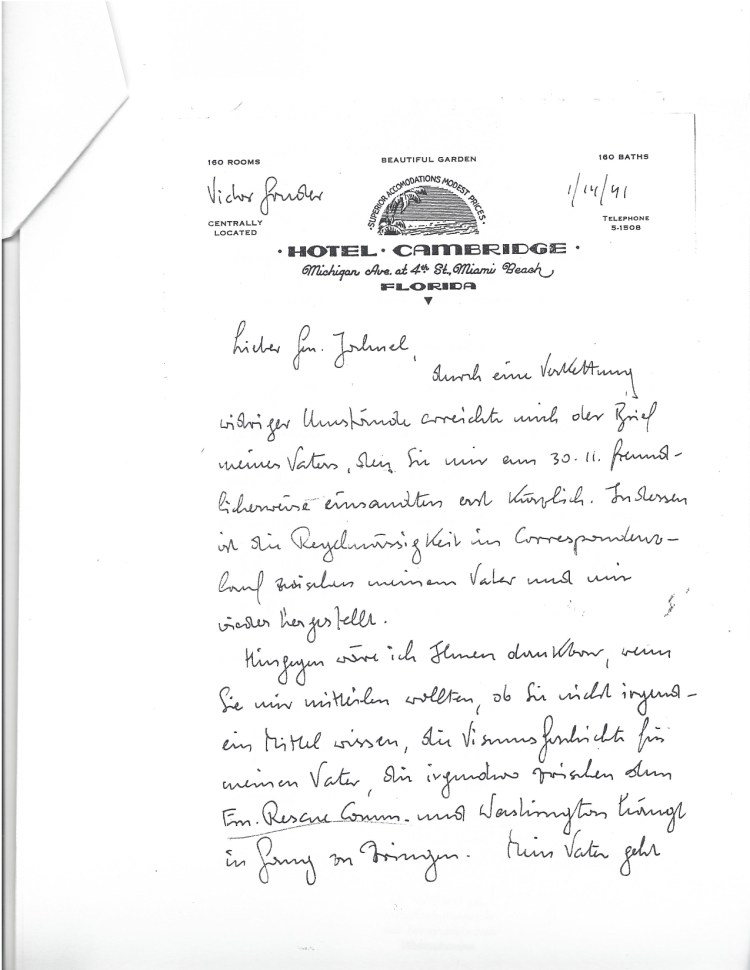

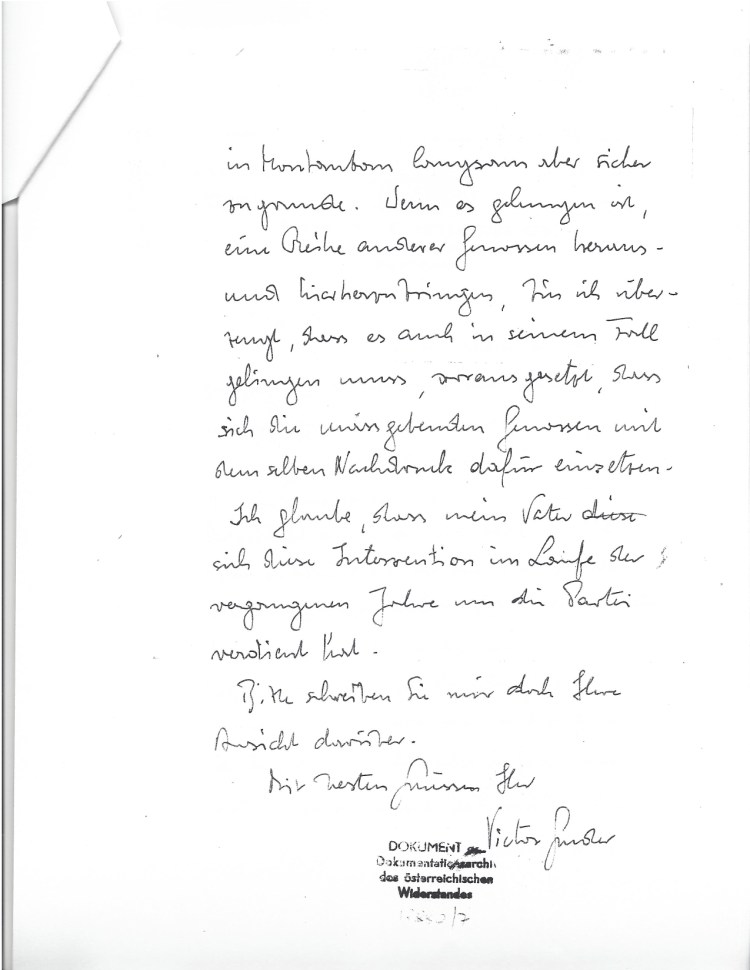

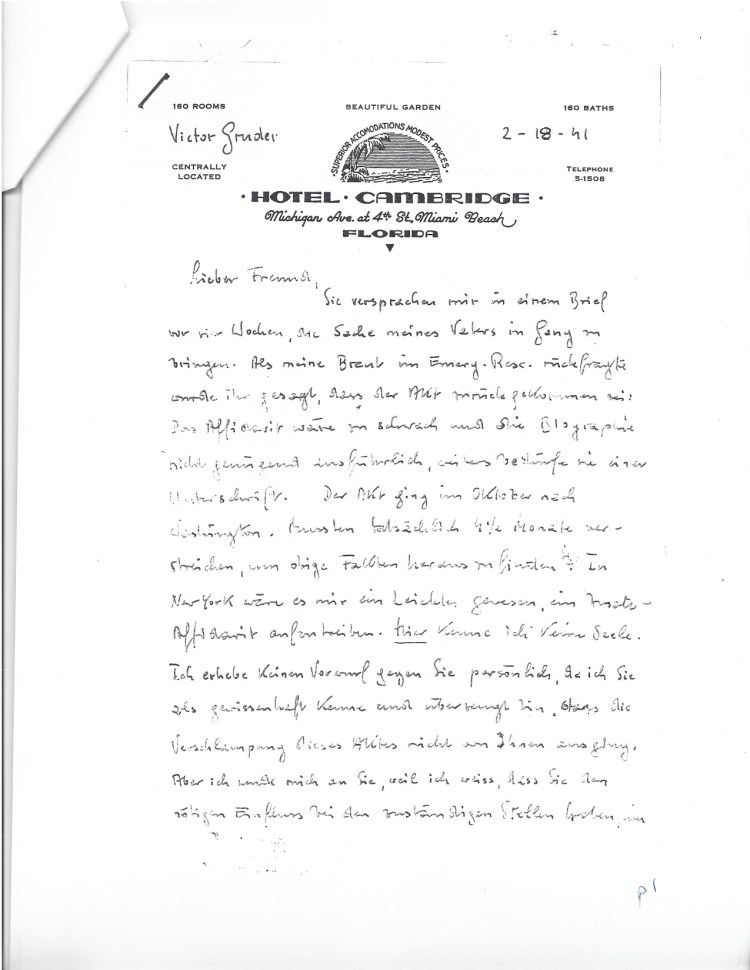

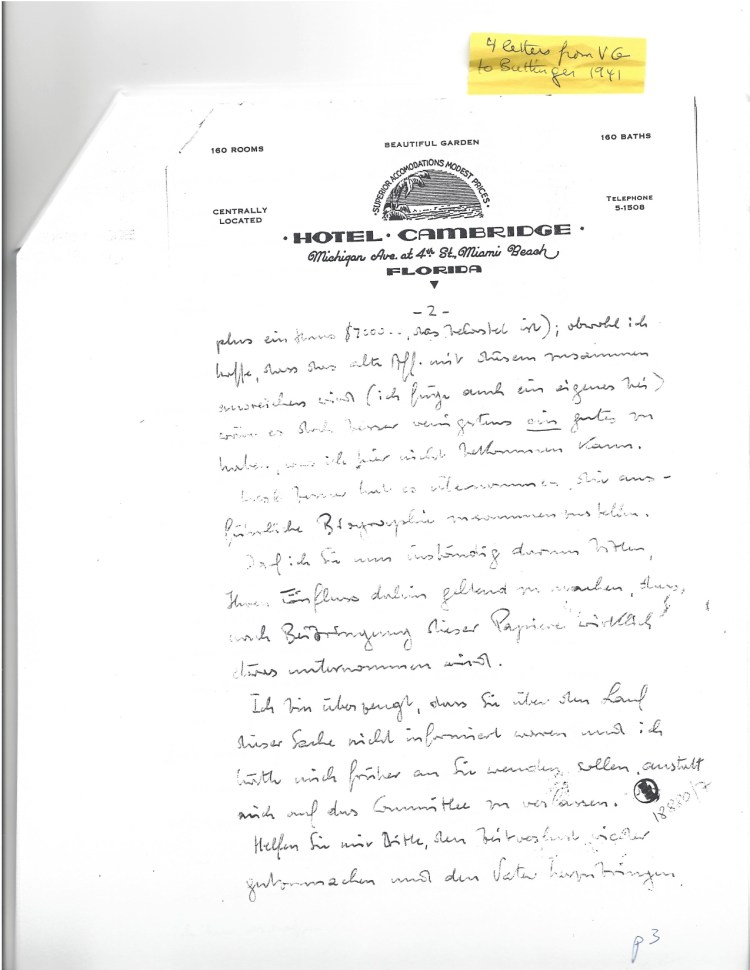

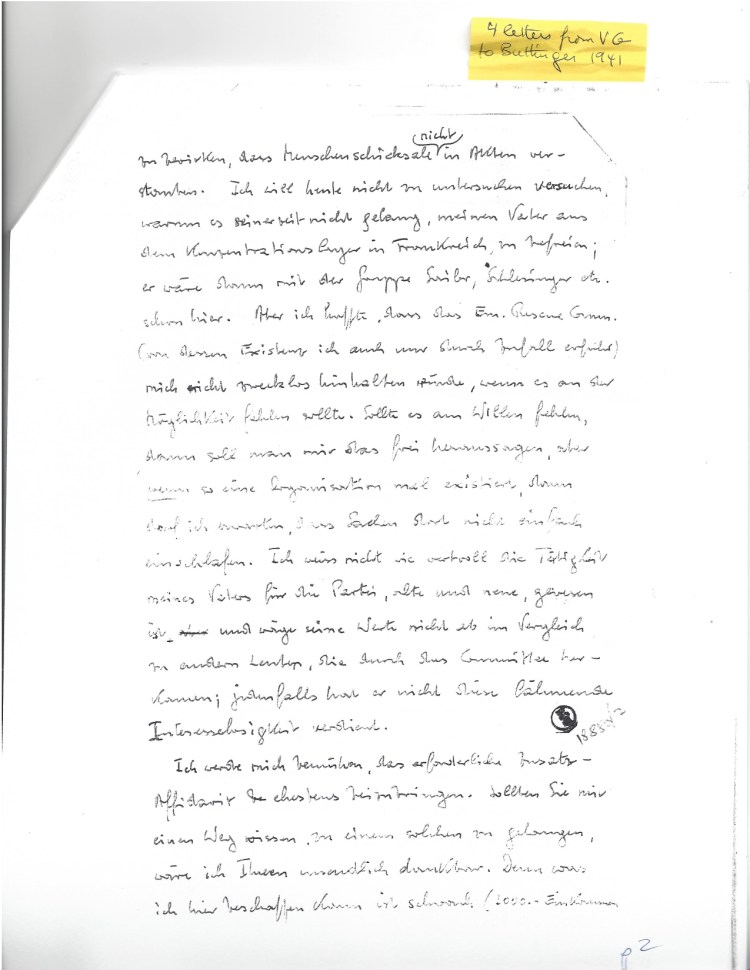

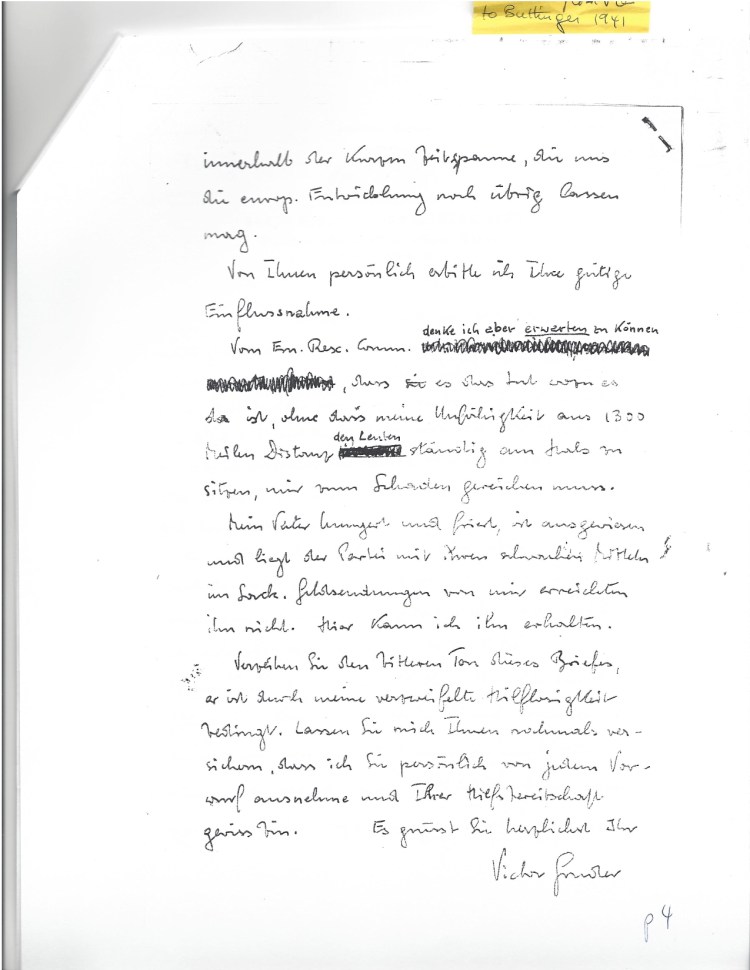

As a matter of fact, thereby hangs a story in which your mother played a great role. I was at the time a waiter in Florida (we were not married,) and I wrote Mommy frantic letters to implore the people in the Austrian Socialist Committee in New York to get my father one of the visums.

And you can imagine that there was a great demand, and I was exasperated because I had learned in the meantime of the fact that it was by their negligence that my father had remained in France while all of them managed to get themselves to the States. [ed: Victor is referring to the Austrian Socialist Committee getting Cicilia permission to bring Ignaz a blanket as described above, rather than getting Ignaz out of the camp and the country.] I learned this through Edmond Schlesinger, and, by some expression of a bad conscience, I knew that pressure had to be brought. I wrote all this to Mommy and asked her to go and make a scandal because things were moving too slowly, and visums were getting scarcer. And she went and saw Mr. Buttinger, the head of the Austrian socialists in exile, assisted by Julius Deutsch, who had been a general during the Civil War in Spain (he headed the Austrian contingent of volunteers from the Republican side. There also was Count Sforza, former Minister of Foreign Affairs in Italy,) and Mommy marched in there and she let them have it. She made a tremendous scandal, and they were taken aback but it was put on the agenda of the next meeting and my father got his visum. Mommy confessed later that she had no idea who the people were to whom she had talked there. She just let go of how she felt, and it was a good thing she didn’t know because, so she says, had she known, she might have felt intimidated in front of all that brass.

Your mother had a knack for that sort of thing. Let me give you a little aside. Many years later, after the war, when a distant relative turned up as a survivor of a concentration camp and tried to come to the States, she needed an affidavit which somebody with means had to give her.

And there was a rich aunt of Jeanette who did a lot of praying and did a lot for the temple but didn’t give an affidavit. So, (I was a witness to the telephone conversation in which) Mommy berated her and told her if she would pray a little bit less and send the affidavit, she could for once in her life have done something for another person. And, by God, it worked, and she sent an affidavit, and Mommy never spoke to that aunt again, which was just as well. I couldn’t stand her either.

Well, back to my father. He got a visum. And he got a passage on the Winnipeg, a French-chartered Canadian boat on which, incidentally, George Herald also traveled at the same time. And they set out for the United States, were stopped by a British warship which captured this Vichy ship and ordered it to Trinidad, where all the passengers were interned.

Now this was not a very severe internment. The British authorities in Trinidad behaved very decently, cables were sent to the States and, I believe after less than a week, perhaps only three days, my father was on another ship and arrived in New York, where we awaited him.

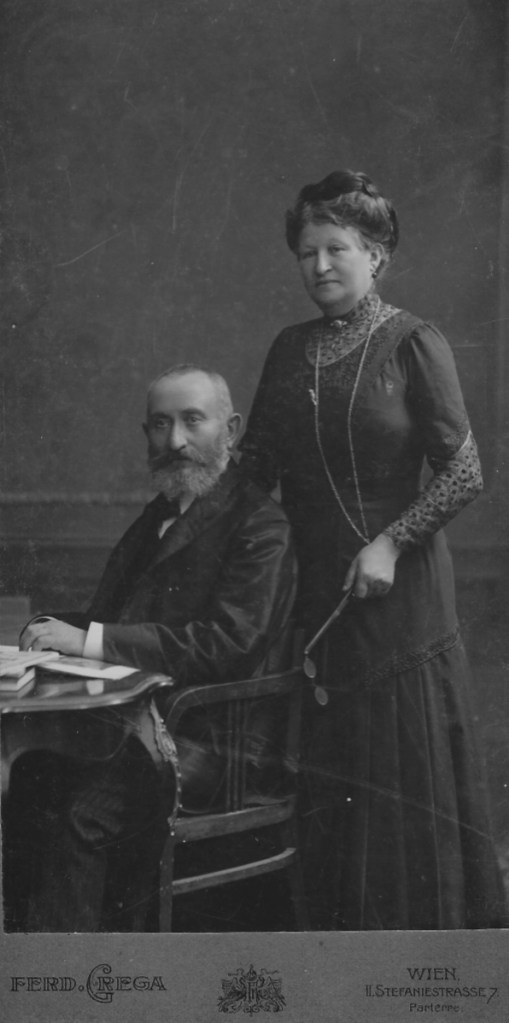

This is sometime in the middle of June 1941. He was a sad sight. I remembered my father always as slightly corpulent, as you can see on the portrait that we have, that we so recently rediscovered [ed: see oil portraits of Viktor and his parents in Letter 6 “Viennese Refugees”,] and when he walked off the ship, he was just a shadow of his former self.

He had long white hair. I knew him only when he was bald. And he was visibly a sick man. He had been a diabetic, something that had led to his deafness, but diabetes was no problem at this time because he had so little to eat in France and didn’t have any blood sugar when he arrived. At any rate, needless to say, there was great happiness and we lived together in an apartment we had rented in New York. Two weeks later we got married – something we had deliberately postponed until my father would be there.

When I was talking about my father, early about my mother, it occurred to me that you never knew your grandparents, neither on Mommy’s side nor mine. As a matter of fact, neither Mommy nor I knew our own grandparents. Perhaps Mommy has, during the time you now spent together, told you something about her own childhood and her parents. Let me try this for my parents.

Both were born in Galicia – my mother in a town called Tarnopol and my father in Brody. My father came to Vienna, I believe, at the age of two or three. My mother must have been older. I don’t exactly know when she came but she had already started to study to become a teacher. I don’t know exactly how far this went, at what age she moved to Vienna. My grandfather on my father’s side had been, I believe, a merchant. I do know that they did not live in a ghetto but apparently in a Jewish sector, however I know, through my father, that his father already was not a practicing Jew but a free thinker. And my father was educated in that faith, or non-creed. And his mother was a very beautiful woman. I can tell from pictures I’ve seen although I have no recollection of her or my grandfather, notwithstanding that I am on a picture with them, but I think I must have been two or three years old.

Now there were four Gruder brothers. One of them, Bernard Gruder, was the father of Herta Rose. [ed: Victor’s cousin. See “Origins, Childhood and Education” for a brief summary of Herta’s heroic life.] He was financially not very successful. A very sweet, good-hearted man who, I believe, was spending most of his life being a salesman and not doing too well at it.

Another brother was an engineer, lived in Innsbruck, built cable cars and was married to a non-Jewish woman by the name of Jenny. I disliked that woman so much that I retained an aversion against the name Jenny and could never accept it that Mommy was called by both her sister and her brother “Jenny.” I never did that and called her Jeanette from the first day we met. Uncle Julius [ed: see Letter 3 “Jail and Un-employment”] had four children, three sons and one daughter. We didn’t get along too well with each other, except for the youngest son who was the only intelligent one in the family. He was my age and perhaps he was the most intelligent. He committed suicide at the age of eighteen or something. The daughter was pretty but dumb, my cousin. And the two other boys were just incredible – stupid and useless. And one of them later married Francie, whom you know.

The fourth brother [ed: Moritz] was an actor, a very successful one, extremely good-looking (sort of in a Paul Newman sort of way)

and he played in the Burgtheater and was a real ham but successful. We didn’t see much of him. We did see a lot of Uncle Julius who, every time he came to Vienna, stayed with us. I’ll tell you more about that later.

My mother’s family must have come from rather modest circumstances. I don’t believe they lived in the ghetto but, again, in a Jewish schtetl. And my grandparents on my mother’s side had a little shop in Vienna. I remember my grandmother, my mother’s mother, best because she lived longest. But they were simple people, and I cannot say that I had any relation with them, very close relation. I was very young, I believe about five years old, when my grandmother, the last of the grandparents died, my mother’s mother.

My father studied law and when he made his law degree, he got married. One didn’t get married before one had one’s degree. And he was then already very engagé as a socialist and, while I don’t know too much about their life together before I came in this world — rather before I was old enough to observe anything — but when I was, I realized that my father was a rather domineering personality, my mother was a long suffering Jewish mother, and she was treated by my father in what I, retrospectively, consider to have been not a very kind way. There was no zärtlichkeit, there was no tenderness. Tenderness. All three of us never were capable of showing zärtlichkeit by gestures, by stroking, by embracing. I’m quite sure that my father loved my mother. He would have died for her if that would have been necessary. But I don’t think he ever would have gotten it over his lips to say, “I love you.”

Now, when I was a little boy, I aped everything my father did. When he pushed back a dish that my mother put in front of him, saying he found it burned or didn’t like it, I immediately imitated this, to the chagrin of my mother. When he declared that he doesn’t like bananas, I didn’t like bananas. And, even later, when I already was in my teens, a period I told you already something about, I just ignored my mother. I behaved like a bastard to her.

I’m saying this in retrospect with shame because it took a moment, and I know what that moment was, when my attitude to my mother changed and when my whole outlook changed. And that was at the time when we were arrested. The dignity and the self-control that she showed when both her husband and her son were arrested by people with guns in their hands and left, she was left alone and there was no tear in her eye. She didn’t want to cry in front of the people. And later she came and visited her husband, her son, in the police lockup and again, there was a police officer present, and she controlled her emotions superbly. And it was at that moment, at these two occasions, that I suddenly realized what a wonderful woman my mother was. I cannot even talk today about it without feeling emotion and shame because it shouldn’t have taken any outside event to show my love. I had no business taking her for granted but, at the time, until then, I was a playboy with no responsibilities and no sense of guilt for not assuming any. And that only changed when this rather traumatic experience of the arrest came.

It was in jail where I changed. It was the first time that I went hungry. I couldn’t send out for food because I didn’t have any money and there was none at home either because my — all this coincided with my father’s breakdown of health. He suddenly became deaf, which later meant the end of the office practice. It wasn’t a conscious change that I underwent but retrospectively I know that these four weeks in the police lockup made me mature and it reinforces my theory that adversity can be a stimulant and adversity it was, and with a bang! The séjour in the cell I shared with Dr. Eisler was a baffling experience. Nothing happened. Nobody came. We were not summoned anywhere. Yes, at one time, some police officer showed up (incidentally, I may have told you this before. At the risk of repeating it, I shall.)