Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 3B, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

…………………..

They asked first Eisler’s name, birthdate, and so on. And they knew who he was. And they asked me. And a police officer said, “Why are you here?”, probably referring to the fact that I didn’t fit into this illustrious company. I was nobody. But I answered him that I had hoped he would tell me, and, with that, he left. And then, nothing. One day, about four weeks after we had been arrested, we were – you know, I shouldn’t call this an arrest; an arrest is a legal concept where you are being told that you are under arrest. That means that there is some suspicion of a punishable act that you may have committed or are suspected of having committed, and that constitutes an arrest. We never were arrested. We were merely invited to follow this bunch of civilian hoodlums to the police and were locked up. That’s all.

So about, as I said, in the fourth week, I was summoned – oh yes, at one time I had the visit of my mother, but these were the only outside contacts. And I knew through her that my father was still there, and that Heinz had been released. When I was summoned, I was asked my name and birthdate and so on, and also my religion, and I answered the man I was Jewish. He told me, “It says here that you are confessionslos,” that means not belonging to any religion, and I said, “For you, I’m Jewish.” Well, he told me that I cannot make wrong statements, whereupon I asked for a postcard, which he was obliged to give me, because I declared that I wanted to re-enter the Jewish community. And he gave me the postcard and I did. Now, as much without reason as I had been arrested, I was let go, two days after, or one day after, this interrogatoire, and I went home.

My father had preceded me by two hours but, needless to say, there was great joy. At this time, I had no difficulty showing my love for my mother and — you’ll never guess what was an experience which I still remember as having been the greatest joy of being home again — it was the possibility to enter a toilet and be able to lock it. I mentioned it to my father, and he fully understood. One has to have been in jail to know what it means.

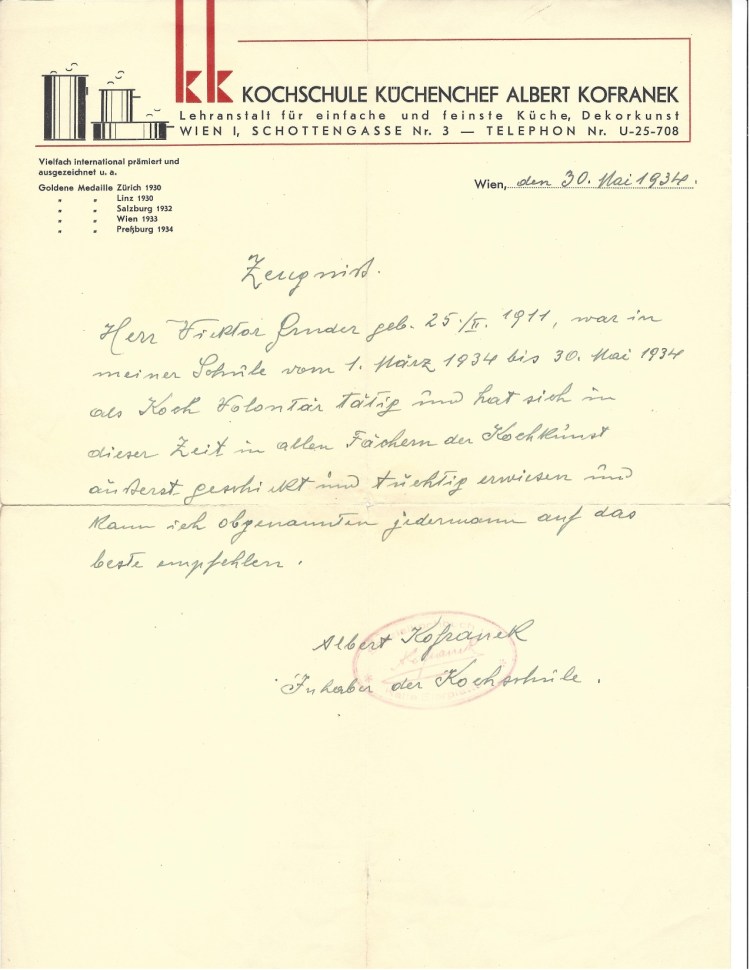

Well, with that a very tough period started. My father’s practice was shut because of his health, because of the event, and it was quite clear that I had to do something to keep the family going. My mother, in her quiet and efficient fashion, took over. She decided to rent some of the rooms in our apartment and — sub-let them — and I tried to get something going and I realized that I had to leave Vienna, soon, because it was quite clear that there was no future for me in Vienna. I figured out that perhaps the hotel business would be something for which an Austrian background might be a recommendation. I went to a cooking school, to Mr. Kopranek.

Yes, indeed, I learned cooking. I have since forgotten it and I am painfully aware of it now that Mommy was away. But then, I had learned something and eventually I went to hotel school. That was not a money-making proposition. I did a stage at the Hotel Imperial and finally decided to go to Bad Ischl.

Now here I have to interrupt….[ed: explanation of previous tape erasure]

It is psychologically interesting that I was recreating the situation so clear that I had to make money and help the family, that my memory played me a trick and I originally told you, and was quite truthful about it, that I became a nachtportier, a night concierge in the Hotel Münchnerhof, although this happened much later because that was a money-making proposition. But, to set the record straight, when I said my father’s practice was shot, it doesn’t mean that no money whatsoever came in. There were outstanding debts by clients. There was some paperwork still to be done. I was able to do some things for him in the office. And we still had my cousin, Arthur Brüller, who was a junior attorney and worked in my father’s office. (And it didn’t last very long. He left and took all my father’s clients along. Quite a gentleman, he.) But we somehow muddled through while I did these extra-curricular activities, training myself in a sellable skill. Also, my father was not completely unable to function. He was very hard of hearing; he was not entirely deaf. And he still operated in his office, but less and less.

In the lost tape I related a story which is worth repeating, although it happened actually much later, because it’s essential that I — it happened at the time when I already was earning money and was supporting the family to a very substantial degree. And that is necessary for the story. It has to do with a visit of my Uncle Julius, who came once more from Innsbruck and, as usual stayed with us, and it had always bothered me that his rather crude and stupid sense of humor entailed calling my mother “meine Cou…..sine,” which he wasn’t, but the emphasis was on “Cou…” [“kuh” meaning “cow” in German] and that was his level of sense of humor. And, generally, he always teased her, and he did it again when on this visit.

Now I had enough of this and told him that I had listened for years to his behavior vis-à-vis my mother, I was not taking this anymore. This was during dinner in the evening, and I asked him to leave, right there and then, leave our house. It was total bafflement on his part, my father’s part. I talked myself into a good deal of anger and threw him out that very evening. This act, when she learned about it, earned me the everlasting gratitude of Herta [ed: a paternal cousin of Victor] who hated his guts as much as I did. Many years later I learned that it hadn’t helped him, that he had been baptized a Catholic and had a Catholic family which denied him completely. His wife left him, his children denied him, and he eventually perished in a concentration camp. While I had disliked him, I never thought that he deserved that end. An end, incidentally, which was also that of Herta’s father [ed: another of Ignaz’s brothers] and mother. The last brother [ed: of Ignaz,] Moritz, had, I believe, died before — I don’t know how he ended up.

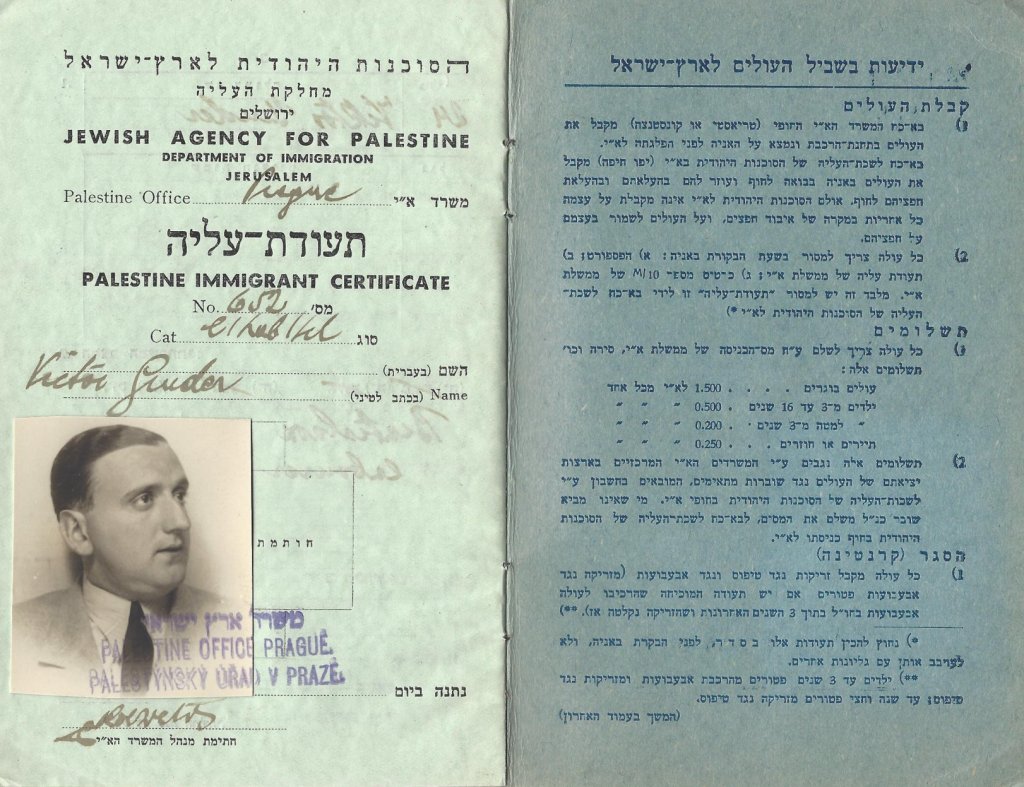

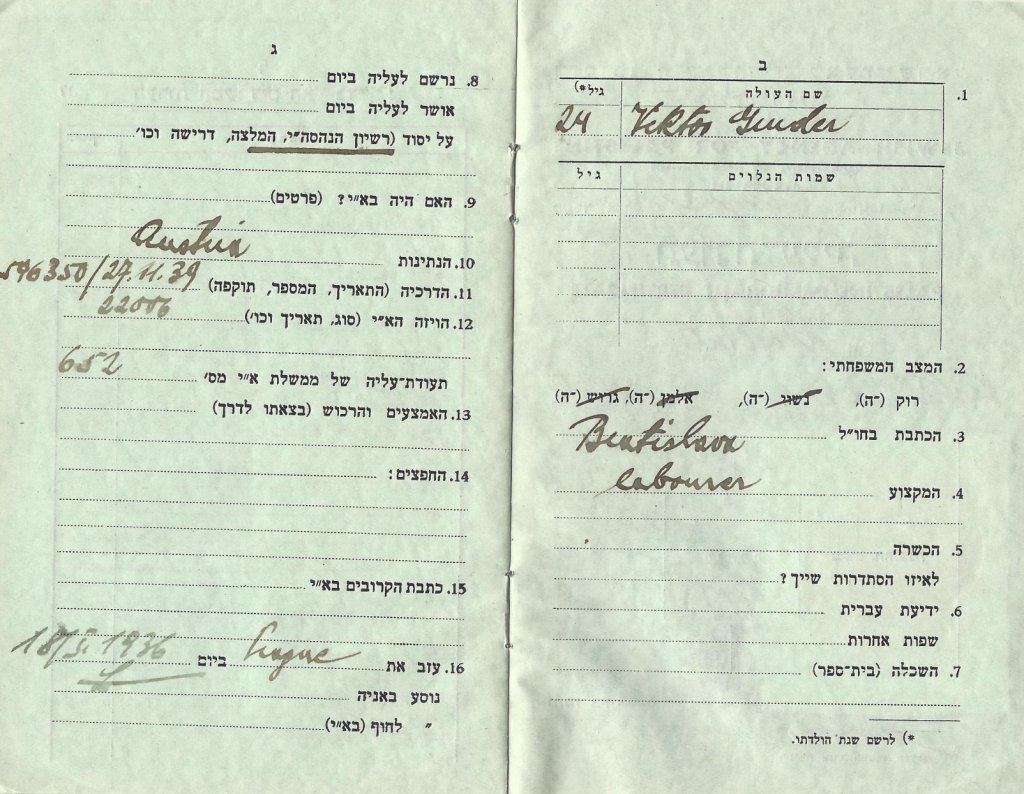

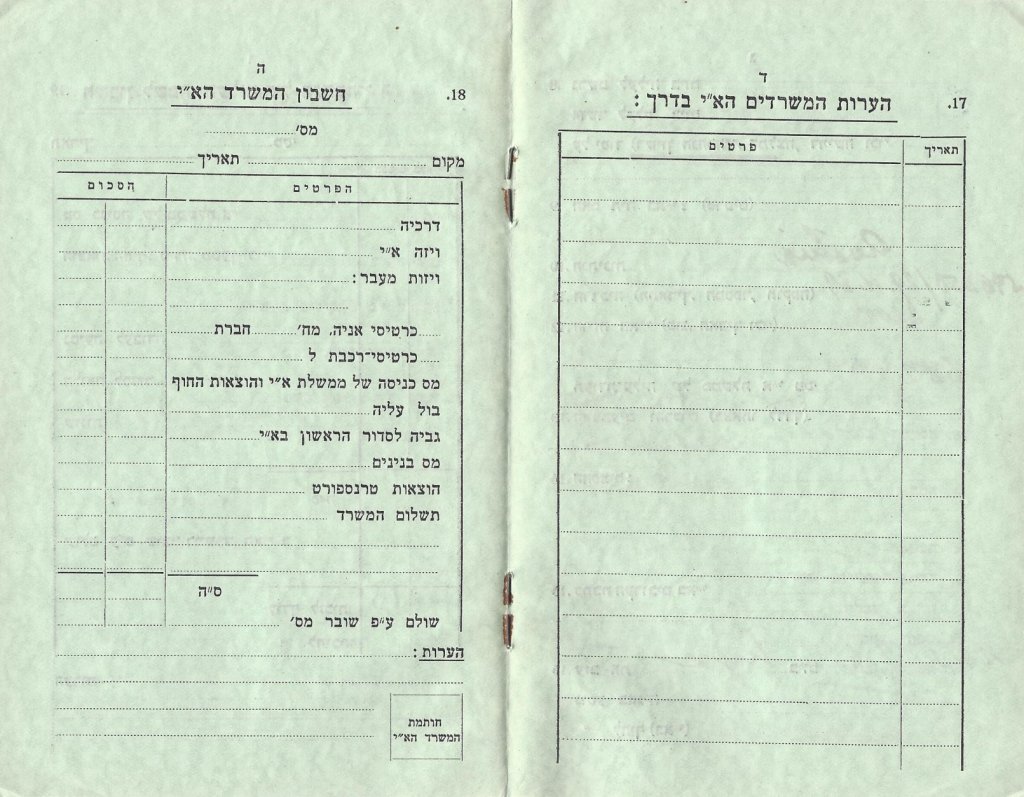

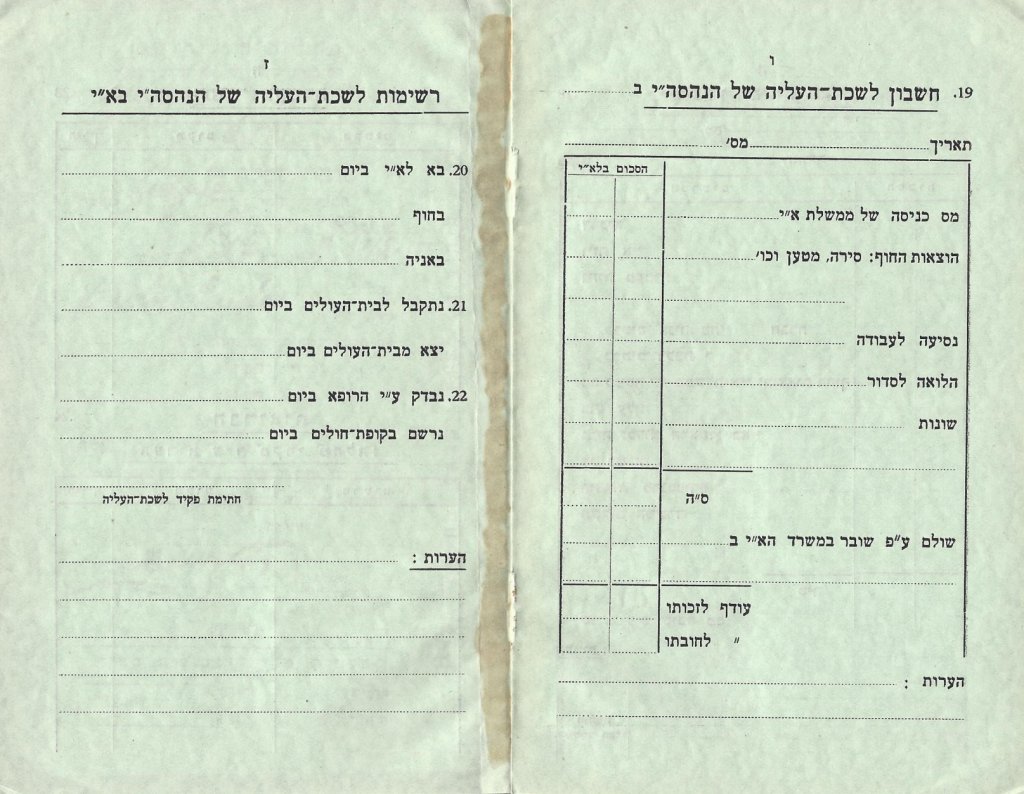

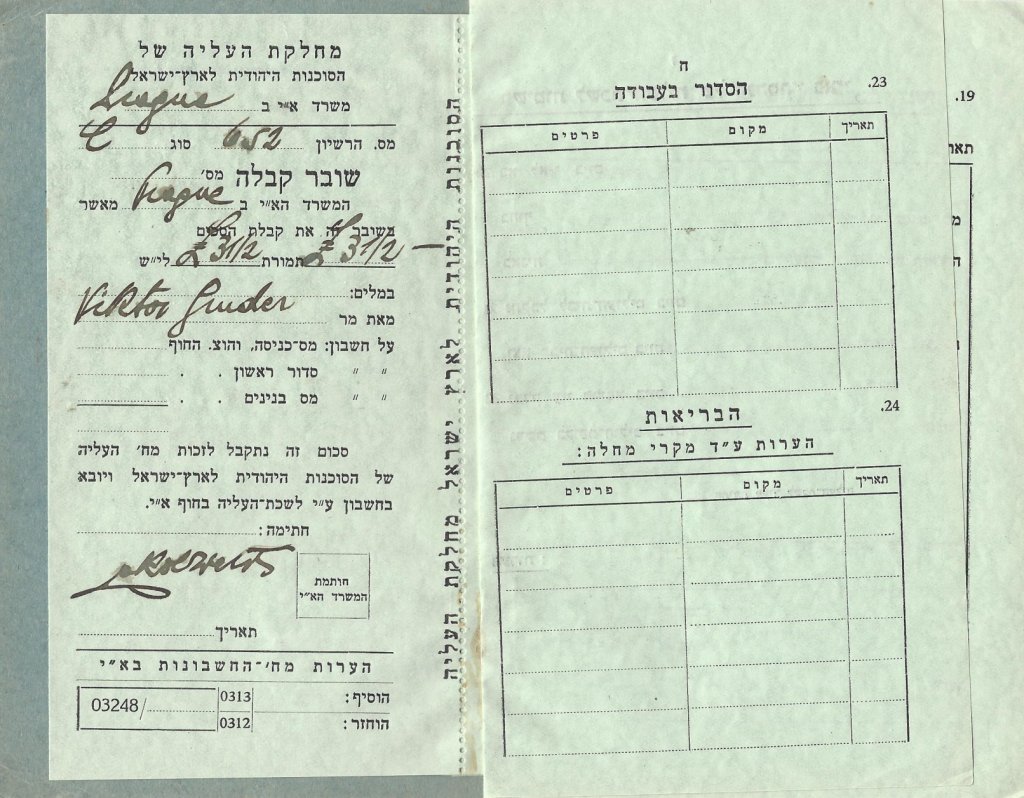

Well, back to my story. I knew I had to leave Vienna and somehow the idea came — it was a rather obvious idea to hit me — perhaps I should try my luck in Palestine and, through connections with the socialists in Prague where the Austrian underground socialists had their headquarters, in sort of a government in exile. And I went to Prague to get a certificate which was an entry visum into Palestine, but it took some time to get this.

And eventually I did, and now the question arose how to finance the trip to Palestine. There wasn’t enough money. And then a lucky thing happened. A friend of my father was the director of a transport company, a big moving firm, Shenker, a worldwide net of offices, and they had a rather strange request to satisfy. A rich Jew from Cairo had died in Vienna. He had been the owner of many department stores in Cairo. He died in Vienna, was interred in a lead coffin – that is, in a coffin and that was put into a lead coffin — and he was interred because the family wanted him eventually to be shipped back to Cairo. I say eventually because, according to Austrian law, he had to be a year buried before he could be moved out of the country. And Shenker was charged with that move. Well, it occurred to the friend of my father that since I wanted to go to Palestine, and the family of the Egyptian gentleman was willing to pay the trip for somebody going to Palestine, that I should accompany the corpse. Well, according to Austrian law, a corpse transported by train had to be placed in an otherwise empty freight car and somebody had to accompany that train. That doesn’t mean he had to sit in the freight car but somewhere in the train, just to be on hand if anything should happen to this car. God knows why the legal provision was as it was. But, at any rate, I went and eventually came to Trieste, where the coffin was put on the ship….

[ed: this continues on Letter 4 “Self-Reinvention” but you will need to advance through Extract 1 directly to Extract 2 “Egypt, Palestine, Hotel Work”]