Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 4A, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

……………………

The poor people, that the price of the trip included a metro fare to the hotel. Well, you can imagine their reaction when I told them that, if four of them got together and took a taxi and I paid the cost of the metro fare, that it would be only marginally more. And we eventually got to the hotel. A horrible hotel, Hôtel des Balcons, near the Odéon, a small street near the Odéon. And the people found themselves assigned to rooms where two strangers, people who didn’t know each other 36 hours before had to sleep in the same bed – you know, French beds. In Vienna there were twin beds, in Paris a single bed. And there was absolute pandemonium. People objected, yelled and screamed at me. I screamed back at them. It was an atmosphere of pure hostility until I hit upon the idea of telling them, “Look you can either adjust to the situation and enjoy a week in Paris, which is a wonderful city, or you can stay mad and spoil your stay.” Somehow, I calmed them down and told them that I had arranged for a bus with a guide the next day for a first tour through Paris, and I had made such an arrangement. And the next day (incidentally, they also were entitled to a breakfast against coupons in one of the restaurants on Boulevard St.-Michel and I took them to that restaurant,) and then we started out on the tour which, incidentally, all the people booked for.

This tour business had been my own addition. The people in Vienna had no objection. It was my own affair, so we set out on the tour. At the time there were no loudspeakers. There was sort of a megaphone into which the guide spoke and he one of those totally uninteresting, impersonal guides, strong accent, and he got on my nerves very quickly, and I told him, “Look, I’ll see to it that you get the tips, but give me that megaphone — let me do the guiding.” And with that I started to tell the people, “Look, this is a city I love and if you want to know why, and if on a strictly subjective basis, you allow me to tell you, perhaps you can possibly share my enthusiasm.” Well, this was a novel approach for guides and apparently it was successful because the people immediately signed up for a second tour where I no longer had a guide.

I just hired a bus and they signed up for a “Paris at Night” tour where we went to five nightclubs. All this I copied from the tours which the American Express or the Cook’s Tours made. In fact, I don’t remember if there was an American Express, but Cook’s was there, and others, and I only charged about half of what they charged, but the total cost for me was the cost of the bus. The rest was pure profit for my work, and this was rather a joyful experience because it is fun to tell people about something you love and to arouse their enthusiasm. I must have managed that rather successfully because, as the people got back to Vienna and other tours came (there came one tour every week,) they started singing my praises in Vienna, with the result that I was approached by other Viennese travel agencies and ended up representing thirteen of them, got all their groups, which I then bunched together. Thank God only the one group had to be stuffed in that impossible hotel. The others had hotel arrangements of their own.

And throughout the World’s Fair, I guided people through the World’s Fair, through Paris, and I had invented a number of tricks which worked out very well. I would take people by metro to the Place de la Concorde in the evening, when the lights were on, and told them to walk up the exit with their eyes closed and only open their eyes when I tell them. I told them how many steps there were and open their eyes only when they were standing on the Place de la Concorde, because I did remember my reaction when I saw it for the first time. It was quite a theatrical success. Now there were also numerous agreeable experiences in connection with that.

At one time there came a group from the Friends of the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna. They were guided by a professor of art who was going to guide them through the Louvre. I asked permission to come along, and the man took them into the Louvre, told them, “To the left, downstairs, the Romans and the Egyptians. Upstairs, the Picture Gallery. I meet you again in three hours,” and off he went. Well, the people were standing there. I don’t know whether you know how tourists are, inexperienced tourists. They are like a herd of sheep, they are totally lost unless you take them by the hand and lead them, and there were dozens of people standing around, not knowing what to do next, grumbling about the fact that this wasn’t what they had bargained for. So, I told them, “Look, I know something about the Louvre.” So, I ended up guiding them through the Louvre.

Guiding through the Louvre or through Versailles at the time of the World’s Fair was murder because there were such masses of people, when you went in with a group you had to somehow make some arrangement so that you wouldn’t lose them. There was one lady who had invented holding a rose up in the air; the guide of that group had a rose. Well, I held a newspaper high and made myself known that way.

That was also during that particular tour, in one room we saw frescoes by Fra Angelico and, as I looked around, I saw Marlene Dietrich with black eyeglasses, with Rémarque, Erich Maria Rémarque, who was then her boyfriend, and they were looking at the picture. I had recognized her truly by her legs. She had fantastic legs. Well, I made my spiel in front of Fra Angelico and said, “This is a masterpiece of the Renaissance, and over there you have a masterpiece of our time,” and identified Marlene Dietrich, which earned me a smile from her and a great sigh of astonishment on the part of my tourists.

I also invented another thing which always came off. When we came to the Mona Lisa, I invited people to look before I tell them anything and then told them that I will “…first of all, tell you the questions you are going to ask me. Number one – you imagined it much bigger. Number two – am I sure that it is the real one and not a copy? Number three – you had imagined her more beautiful. Well, to answer your questions, you are thinking of a great picture; it is so famous that when you stand before it, it looks in comparison small. That has something to do with your expectations of greatness. As to her being the real thing, it is the real thing. All experts are agreed on it, notwithstanding that it had once been stolen and stayed in hiding for a while. It is considered to be the original. But what matter — it is, to you, the Mona Lisa. That is what matters. And why you expected her to be more beautiful is because she has no eyebrows. You see, during the Renaissance, women shaved their eyebrows, and they were painted that way. If you can imagine penciling in eyebrows, you would find her as beautiful as Leonardo found her.”

Well, these were the little tricks of the trade. When we went to the nightclubs, I had a small group. I was on my own and the only way I could get decent seats for my group was to bribe the head waiter at the Bal Tabarin and the Moulin Rouge and I had to be there before the big tours came, like Cook or American Express or whatever it was. And, since I had to be there early, we had to stand in line and during that time people get impatient, so I had to tell them stories, jokes. I acquired quite a fund of jokes for that purpose. And the people apparently had a good time. As a matter of fact, I too had a good time. First, I enjoyed what I was doing. I didn’t lack for private company because tour guides and ski instructors seem to have incredible magnetism for females, lonely females. There was no dearth in that field.

And eventually the season moved towards its end. And shortly before, Edmond Schlesinger, who by that time was in Paris, asked me whether I would mind guiding a tour of Sudetendeutsche Sozialdemokraten.

People who came from the Olympiade — I believe it was held in Belgium — Olympiade of the workers’ sport clubs. They were coming to Paris, all 500 of them. Could I organize sightseeing tours for them? This was sponsored by the socialist paper, the Populaire, and they didn’t have much money or didn’t want to spend very much money on it. So, I organized the following: I turned the people into ten groups of about 50 people a group, and I got myself ten friends — tour guides, sub-tour guides — each one of them taking in tow one of those groups and walking from the République to the Madeleine and such. And I took a taxi, went from group to group at intervals of a few minutes, and as I came to each one of the groups I held my little speech, and went on to the next one. It was a rather trying experience.

In the World’s Fair they were received in the syndicates’ pavilion, where they were addressed by the then-head of the CGT [ed: Confédération Général du Travail], Monsieur Jouault, one of the grand old men of French socialism, and I translated his speech. And then a door opened, and I realized — I heard a voice which I suddenly realized was my own because the speech and the translation came over the loudspeakers all over the World’s Fair. I completely froze up for several seconds or a minute but somehow, I muddled through.

On the last day before their departure, I offered the people to either be taken to the big department stores or to the Louvre and, to my great surprise (I must say I was moved by that,) they unanimously all voted for the Louvre. Well, they were leaving the next day on a special train. I took them to the Gare de l’Est and was going to make my goodbye speech but by then my voice had given out completely. I was absolutely unable to do anything above a whisper and I made my good-bye speech through one of my sub-guides. (Incidentally, one of the ten guides on this tour – perhaps there were more than ten – was Selig, whom you know and who, on this tour, met what later became his wife. They’ve blamed me for that marriage ever since — as a joke, I must add.) And well they gave me a big cheer and I got a personal rendering of the Internationale, which was a sign of great affection. It was an experience I am happy to remember.

I presume Mommy told you that she too had come to Paris during the World’s Fair and one of the people she knew pointed me out at the Gare de l’Est as “that guy” and said something probably positive and Mommy waved that off and said, “Oh, that’s a G’schaftelhuber.” A G’schaftelhuber is something like a busybody, which I was because I had to say goodbye to people distributed over various compartments and was indeed busy. Well, she remembered that later on; however, we never met at that time.

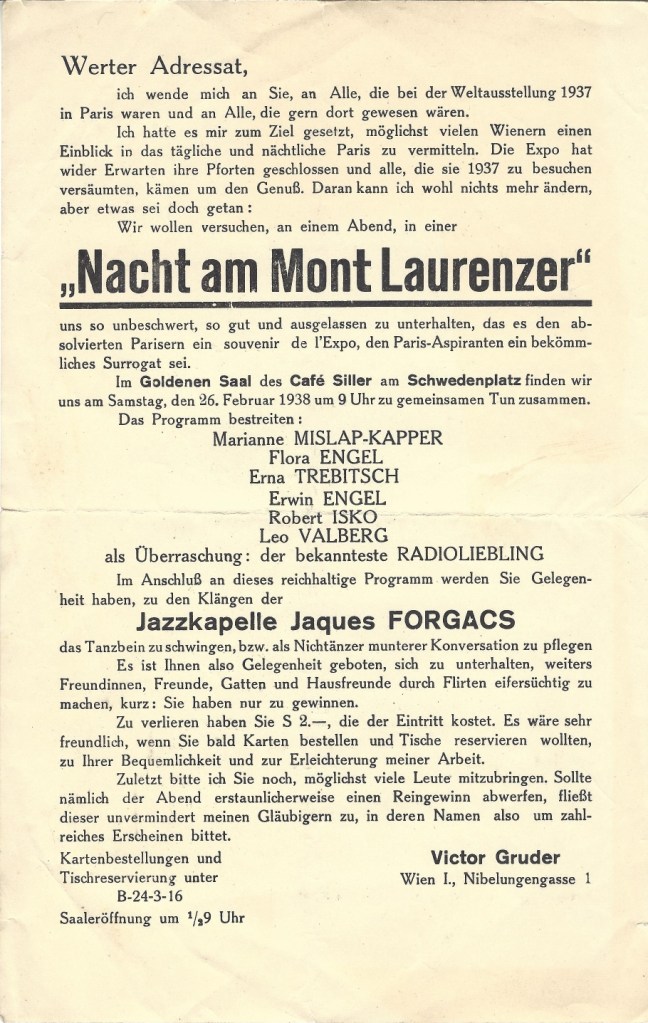

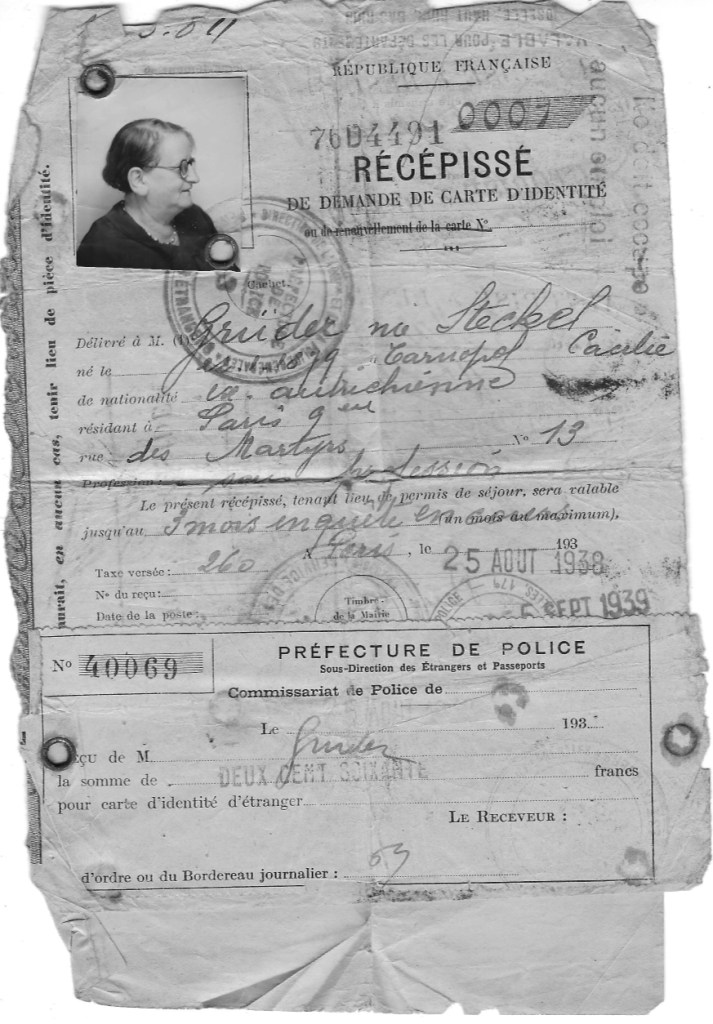

One fallout of being in Paris at the time was that I got myself a carte d’identité, or rather I got a récépissé [receipt, proof of application] for a carte d’identité because it took some time to get the real card. And when, this time armed with a little bit of money, I returned to Vienna and I don’t know what my plans were (besides the fact that I certainly didn’t want to stay in Vienna,) and I organized an evening, a benefit evening, and I made no bones about it: the benefit was to finance my own trip.

I cannot tell you to where, I didn’t know, probably back to France without knowing what I would do there. And I invited to it the people who for years had come to our musical evenings.

People bought tickets for it, and it was a successful evening, and shortly thereafter came the Anschluss [ed: 13 March, 1938]. In fact, something like a week [ed: 2 weeks] after. And there begins another story.

The Anschluss meant that Hitler had decided to annex Austria. He marched, with his troops, towards the border, one day after he had told Schuschnigg that he wouldn’t let him bargain with him. Schuschnigg, the Chancellor of Austria, resigned and everybody knew that this was the end of Austria. It would be annexed. We – “we” being Dicky, her brother, her fiancé [ed: Frieda Neumann, called “Dicky”; her brother Otto; and Ludwig Kalmus, called “Viggi”. Victor, for his part, was often called “Viki”. Thus Dicky, Otto, Viggi, and Viki,] and I – were sitting in her apartment and decided we had to leave. We had to leave before Hitler would come. They had marched and were approaching the Austrian border and we knew we had to get out the next day. We mapped it out and we made one resolution which stood us in good stead: we will make mistakes and we will not reproach ourselves the mistakes because at least we are trying to get out. We will not wait until we are slaughtered or what have you.

Having decided we would leave, we determined that it would be best to leave towards Italy because the borders of Czechoslovakia were already closed; Hungary was no choice; therefore, Italy. And we would leave with a certain train the next evening but, since it was already known that masses of delirious Austrian Nazis were roaming the streets on the evening of the day of which we decided this (they had decided on a torch parade) and we had to get to the railroad station with suitcases, doing this in a taxi was dangerous because they were attacking the taxis and turning them over. So, we agreed that we would bring our suitcase to the Sudbahnhof, during the day at a time when no trains were leaving, and doing that by trolley car, and would deposit it there and go by trolley in the evening to take the train — recover our suitcases and take the train. I needed my passport which was in our apartment, and we had to cross from Dicky (who lived in the Third District) to our place (which you know,) and that meant crossing the torch parade.

We decided to take the risk of taking a taxi where we could sit in the background, with Otto and me looking visibly Jewish, and we placed Viggi Kalmus, the blond, blue-eyed one, on the jump seat so that when people would stop the car and yell, “Heil Hitler!” we would all answer “Heil Hitler!” and he would look the part. We went, we took the taxi, we did get stopped, people did stick their hands in, and we never said, “Heil Hitler!” Although our lives depended — perhaps because — our lives depended on it, we didn’t. I think we couldn’t. Otto believes that if we didn’t, we knew that calling “Heil Hitler” and then being discovered being a Jew, would have been worse and perhaps it was fear that kept us. Whatever. We didn’t. We did get through, got my passport.

Georg Gollmann lent me the money for the train trip, and I went to the station the next morning, bringing my suitcase there, deposited it, found all the porters with brand new armbands with the swastika on it. And I asked one in Viennese dialect whether there were any special arrangements, any requirements for people to leave — passport, visum, exit permit or anything, here’s what I had in mind. And he told me he doesn’t know but I should go to Room Number 10, there I would be told. And I walked into Room Number 10 and found myself amongst something like twenty-five policemen, all with swastikas. I’m standing in the full light of the window, and they wanted to know what I wanted to know. So, I told them in Viennese dialect which, thanks to eight years in a school in the workers’ district, I spoke perfectly well, that I had to leave that evening with that and that train, and I wanted to know whether anything special was required. Are the trains going? Is that train leaving? And got the answer that “Uns ist offiziell nichts bekannt.” [“Officially, we don’t know. “] Well, that was fine. So, one guy volunteered that they do look at the people leaving, whether they take jewelry and money out, and I had the presence of mind to say, “Well, as far as I am concerned, they can look into my ass because I have nothing. I am going back to Paris to resume my work as a waiter there, and I have nothing to hide.” Whereupon I got the answer, “Well, that’s not for people like you. That’s for the goddamn Jews.” And with that I left.

The evening came. We arrived unscathed at the station and very calmly and quietly sat in a corner, waiting for the train, for the people — for the passengers on the train before us to pass through the examination by a bunch of people in swastikas who were sitting at desks and going through the suitcases. During a lull one of the men waved us over, he pointed with a finger to come over, and said, “You gentlemen are academics, aren’t you?” Academika is the German word; it means you are students. We said yes. “Where are you going?” “To Milano.” The man was a student. He was obviously embarrassed. But that’s not what we had imagined it would be like. And he made a point of saying, “Well, open any one of the suitcases.” “Which one?” “Whichever you want.” We did. He made a show of not looking through it, sent us on our way, and said good luck. That, too, existed.

We’re on the train. We sat in a compartment where two Poles were also sitting. They had had a lot to drink. They had come from Poland and were switched to the Sudbahnhof from another railroad station, had no idea of anything that had gone on, knew nothing about Anschluss, Hitler – nothing — and were making a terrible noise. Well, we had the instinct that this could be of help because of Viggi Kalmus’s Polish passport and that would make it three Polish passports. And, sure enough, about half hour out of Vienna, the train stopped, dead, in the middle of the night, still. Not a sound to be heard. In walk three youngsters with steel helmets, too big for them, swastika, guns — and wish to see our papers. Well, Viggi Kalmus was taken care of, we had sufficiently quieted down the two boisterous Poles (who by then realized that something unusual was going on,) and Otto was asked where he was going. “To Milano.” “Why?” “To my uncle.” That seemed to satisfy them. “Where are you going?” they asked me, “on a holiday?” Staringly, I said, “No, I’m going to resume my job in Paris.” “Can you prove that?” And I trundled out my récépissé,

and it was my good fortune that the guy who looked at it didn’t know a word of French but didn’t want to admit it.

[ed: this continues directly in Letter 4 “Self-Reinvention, Extract 1 “Out of Austria”]