Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 4B, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperllink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

………………………..

Extract 1 – Out of Austria, Nowhere to Go

[ed: this continues directly from the end of Letter 4 “The World’s Fair and Escape from Austria”]

They returned the papers and they left. The train was still standing. It was very quiet, and, after a little while, we heard a shot, a gunshot. You can imagine what that did to us. However, the train started to move, and we realized that the gunshot was a signal for the train to leave. We were so exhausted from the excitement from that moment that had passed, and all that had gone before, that all of us fell soundly asleep and we woke up with daylight, coming to the Austrian-Italian border. And as we approached and the train slowed down, we saw a group of SA, Nazis, marching to the border, apparently in order to take it over. Well, were we going to be caught just before we reached the border? Thanks to the Italian railroad men, that didn’t happen. They moved the train, contrary to all rules, to the Italian side without any customs examination. They just moved it ahead of the arrival of the Nazis. And we were in Italy.

Well, I don’t know how to describe the sense of relief but perhaps you can imagine it. We came to Milano, and we were — incidentally, it later turned out that this was the last train out of Vienna — and as we arrived in Milano and somehow were asking questions of people and they discovered we had just come from Vienna, we were immediately surrounded by what grew to a large crowd. And to say that the people were sympathetic isn’t enough. The Italians hated the guts of the Germans. The Italians were not fascists. It’s not in their character. Yes, there were many fascists who benefited from the regime. We didn’t meet any. All the people we met were warm, friendly, hospitable, helpful and we didn’t have any difficulty to eat, to sleep, and Otto decided to stay in Milano where he had been before, and he had friends and thought he can manage somehow to scrape up a living, and Viggi and I were going to go on to Paris.

Viggi, having a Polish passport – and it was a requirement for him to have a visum for France – he went to the French consulate and there, the French vice-consul in charge turned out to be the only fascist we met in Milano. He had no sympathy for refugees. He wasn’t going to give Viggi a visum. Well, I made quite a scandal and carried on and then I hit upon the idea of asking to be connected with a French socialist minister who, at that time, was Minister of Sports in France and I knew him through Edmond Schlesinger, and I wanted to be connected with him. Well, the French bureaucracy being what it is, my mere request was enough to get Viggi Kalmus his visum. However, it had taken 48 hours and during these 48 hours, the French government had decided that Austrians needed a visum and I needed one. I realized that I wasn’t exactly popular with the consul in Milano. He never would give me one.

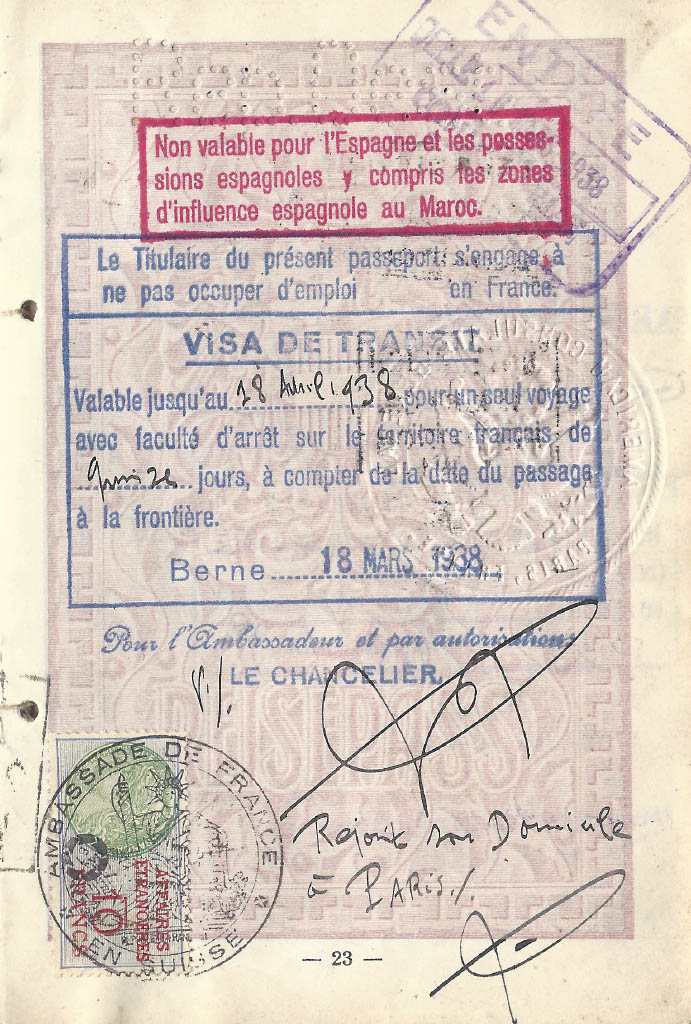

So, we went on to Berne, took a train and went to Berne and, at seven thirty in the morning, we were waiting at a little Swiss chalet which housed the French consulate. At about nine o’clock a man in a loden coat came, opened the door. “What is it you gentlemen want?” We told him we were from Vienna, and we came to ask for a visum. We wanted to see the consul. He said he was the consul. Come in. Very friendly, very nice, and immediately gave me a visum and he held us a little speech in which he said that he was a member of the Ligue des droits de l’homme [Human Rights League], that he was appalled at what had happened. We were the first people — the first refugees — he saw, and he proceeded to apologize to what had happened to us, as if it had been his fault. Now, through all our trials and tribulations, we were quite calm and kept our cool and when he told us, “I’m a consul here. I don’t know how long they’ll keep me in the job but, as long as they do, you can send me your friends, I will give them visums to France,” and then we broke down.

……………………..

Extract 2 – Egypt, Palestine, Hotel Work

[ed: this continues directly from the end of Letter 3 “Jail and Un-Employment”]

…. Yes, and there the corpse was loaded on a ship of the Lloyd Triestino [ed: the shipping line of that name], and I was taken on the side by one of the ship’s officers who told me that it’s considered bad luck to have a corpse on the boat (at least, superstitious passengers may think so,) and would I please not let on to the fact that there was a corpse there and I should have, in the meantime, a good time? Which I did.

We arrived in Alexandria where I was supposed to hand over the papers accompanying the coffin, which in turn was in a wooden box around which delicately they had fixed a black ribbon. And that was unloaded and put on the pier. And I was supposed to turn over these papers to the Egyptian transport man who would pick it up, and that was supposed to end my responsibilities. Well, the ship unloaded, all passengers left, and nowhere was there a truck or a car or a hearse or anything to be seen. I found myself mutterseelenallein [completely alone], with the defunct Felix, on the pier of Alexandria. The ship left and there I was. A policeman came and, somehow, I conveyed the idea of what was in there. He got quite excited about it. I think we spoke French (we must have because I didn’t speak any English at the time,) and he got quite excited and told me, “You can’t leave this here, I mean.” So, I said, “Well, take it away. What do you want me to do?” Well, after about a half hour of this, there showed up a fierce-looking Egyptian in a broken-down truck. He was the transporter.

I bargained somehow with him to take me to Cairo with him, figuring that since the family had paid my passage all the way to Alexandria, the least I could do was convey Felix to his house in Cairo. And we did this in the dead of the night. I crossed from Alexandria to Cairo. I had the feeling that where we drove, that no Occidental had ever set foot there. Every now and then, we were stopped by some police patrol who wanted to know what we carried, and the driver told him, “A corpse.” All hell broke loose. The officer had to be found. It was a memorable night. We eventually got to Cairo about four o’clock in the morning.

I rang the bell of the Leibowitz house, a rather substantial mansion, and announced to whoever opened the door that Felix was there. Whereupon something totally unexpected happened: a terrific howling and wailing began. I later found out that wailing women were hired for important funerals. These are professionals who professionally wail. They, for a slight fee, even tear their clothes, scratch their skin. It’s a quite impressive thing. The mere fact that he had died a year earlier didn’t deter from the decibel level of the wailing because after all, that’s what they got paid for.

Well, I stayed in Cairo for the funeral and stupidly wore a black suit in something like 110 degrees heat. Well, that too I survived. And then found a Viennese banker to whom I had been recommended, who took me into his villa, which was at the border of the desert in a very lovely suburb of Cairo, a very English type thing called Maadi, and I spent some time there, going into Cairo, trying to find a job in a hotel or restaurant business. Well, that turned out to be impossible. My recommendations to the Shepheard’s Hotel didn’t pan out and I went on to Palestine.

There comes now something which is somewhat a hole in my memory. I do know that I did land a job in Haifa in a hotel,

and since I had no idea about the hotel business, I didn’t do a very good job.

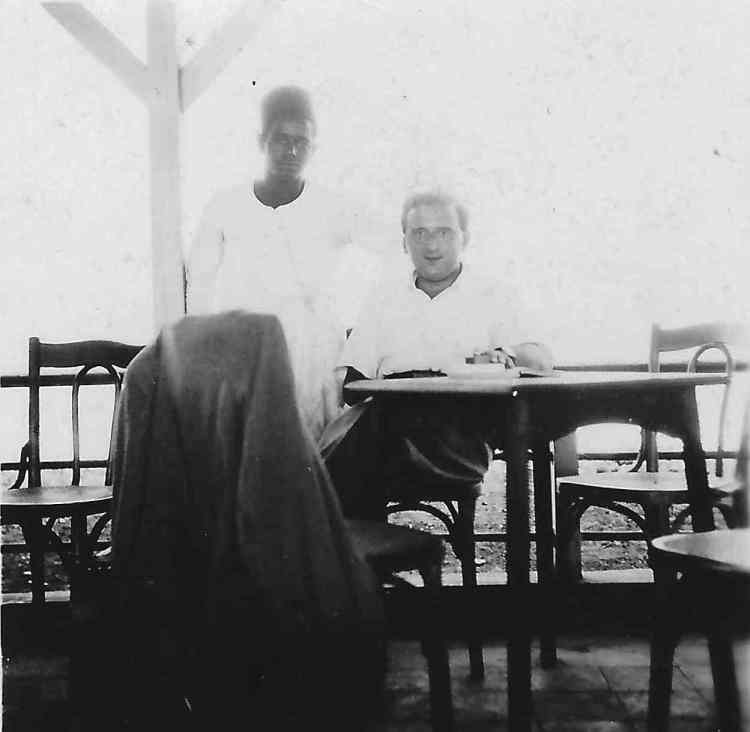

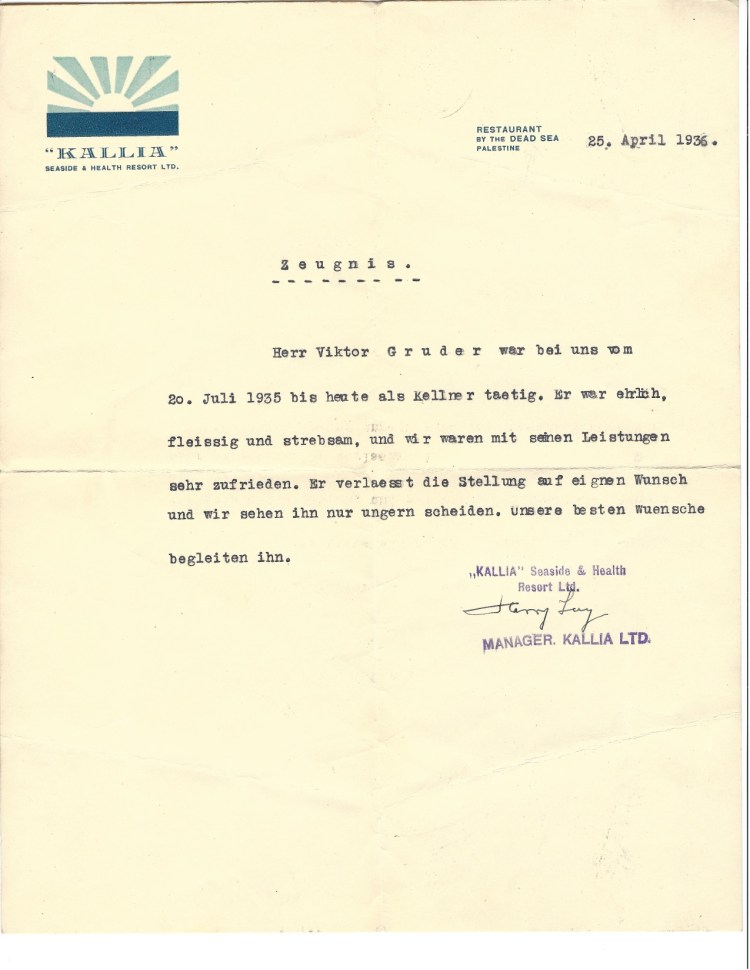

I went from there to a job at the Dead Sea where I was a waiter in an eating place which belonged to the same people who owned the King David Hotel and was licensed out to a very decent German Jew.

And I can’t tell you how long I was there because, to make a long story short, I contracted some very rare disease called Jericho Rose which is akin to some form of malaria, and apparently the high fever that came with it, and which hit me on the boat back to Europe (and I explain in a moment why back to Europe,) it must have done something to my memory bank because there are whole stretches of my experience in Palestine, which stretched over several months, which are blank in my memory while I have no such problem with other experiences.

I went back because I realized that I couldn’t live in Palestine. I call it Palestine because that’s what it was at the time, in late 1934. And I was no Zionist because I had as little use for nationalistic ambitions as I had for lofty ideals, whether they went under the name of communism or socialism. And the whole atmosphere in Palestine struck me as one that required the dedication and conviction of somebody like kibbutzniks, which I didn’t have. I didn’t at that time feel a necessity for a Jewish homeland, which, by no means was it that, at that time. It was a British protectorate, a protectorate where the British ruled with an iron hand and where the Arabs killed Jews from time to time. Quite a lot of them. There were two brothers owning a cigarette factory who paid people money for each Jewish head they could prove they had killed. And the British soldiers, at the time, were not the cream of the British crown. It was an undesirable assignment and undesirables were sent there. As a matter of fact, the Jews had a definition which Fredi Eylon [ed: an Israeli diplomat Victor met much later, in Europe] told me about. They said the British soldier of the Protectorate was a person married to a prostitute who eventually elevated him to her level.

When my tourist visum expired, I decided to return to Europe and not to make use of the immigration certificate which I had, because the number of those immigration visums (called certificates,) was limited, and I didn’t want to deprive somebody else of it. So, I cabled the number of it back to Prague, where it had been issued for me, as being unused and returned on a Lloyd Triestino steamer ship to Trieste. I was woozy and when eventually I asked for a doctor, I had a very high fever. The doctor was a typical ship’s doctor, that means a doctor that nobody else would employ and, being Italian, he treated me entirely with castor oil. Glassfuls of it. In order to make it go down, there was a little cognac on top. Now, it had the desired effect, that is, I spent most of my time in the toilet and, being young and healthy, I survived the doctor. I returned to Vienna.

It just dawned on me that I’m telling you this in the wrong sequence. I said that I was a night concierge in a hotel but, actually, this happened after I returned from Palestine. What happened after I came out of jail was that I realized that money had to be brought in. I wanted to learn the hotel business and I got myself a job at one of the resort towns, Bad Ischl, in Austria with a Jewish man who ran a hotel there and who ran it practically only with volunteers because he didn’t have to pay them. Well, that wasn’t the purpose of my going there so one day I talked myself into courage and walked up to the Hübner Hotel, which was the best hotel in town, and asked whether they had a job for me. It turned out that they did. It just happened to be two days — a day, a single day — after Dollfuss had been killed by the Nazis in Vienna. And, after having arrested the Nazis who did this, the police rounded up Nazis wherever they could find them, and the hotel had just lost their telephone operator who, I was told by the manager, had apparently been killed in one of the fights. So, they were short a telephone operator and, if I wanted the job, I could try it. I told the manager I had no idea how one operates a hotel switchboard and he answered me something which served as a lesson for the rest of my life. He said, “Look, when somebody asks you whether you can do it, you answer yes. Then you try. Anybody who can get a law degree can run a telephone switchboard.” Well, and so I did. I did for two days. It was a busy switchboard however somehow, I managed. And then one day, two days later, Mr. Hübner, the owner, came and told me that he had just fired the chief concierge because he had stolen, and would I want to do the job? “Can you do the job?” Well, I had learned my lesson. “Yes, I can.” And so, from one day to the next, I had a choice job.

Chief concierge in a fashionable hotel was a money-earning proposition and that was a rather memorable time because among the guests were people who knew me. It led to little events like this. One day a man came and asked me whether I had anybody who could type a letter. I said, “Yes, just tell me what.” And he said, “Well, I have a summons for a court appearance in Vienna, it’s a civil suit, and it doesn’t suit me now and I would like to ask for an adjournment.” I said, “Well, just give me the dates and the place and I’ll write it for you.” He said, “Well, how would you know what to write?” I said, “Look, I think I know what to write.” He looked dubious and I was able to tell him, “Look, see that gentleman over there?” (Doktor Pressburger was one of the Vienna’s most famous lawyers.) [ed: Pressburger would be the senior counsel of the defence team which included Ignaz Gruder, Viktor’s father, during the Schutzbund trials in April 1935, less than a year after this encounter. As Viktor had worked for his father throughout his legal training, it is not surprising that Pressburger was familiar with Viktor’s abilities. See “Austria From Habsburg to Hitler”, vol. II, Charles A Gulick, University of California Press, 1980, p. 1327.] “Ask him.” And he did go over, a little bit doubtful, apologized, and asked what this man had told him. Anyway, I could only see the gestures but later learned that Pressburger had answered, “you can rely on it. This gentleman is a colleague of mine.” Well, the man then gave me a tip which was about five times as much as my father could have charged for writing that simple letter.

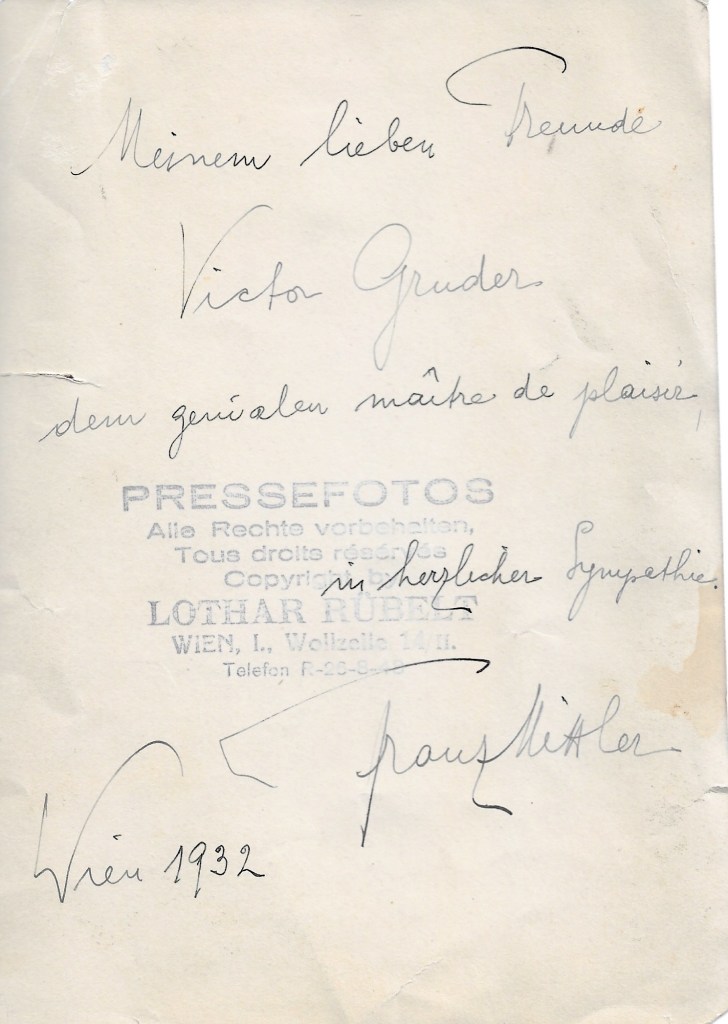

One other amusing experience. There was a concert in town. Joseph Schmidt, he was a little Jew with a golden voice, then very famous in German-speaking countries (no, all over Europe. I recently heard him on the French radio,) and he gave a concert accompanied by Franz Mittler, a good friend of ours. [ed: see Letter 6 “Viennese Refugees” for picture of Franz Mittler at a Gruder home concert.]

And Joseph Schmidt was also somebody who had been to our house. And a Viennese singer, who also was in town with her husband and Franz Mittler. This was sort of a threesome, and they came to visit me, and we chatted. They didn’t stay in the hotel. They chatted, and that evening when Schmidt gave his concert, I turned the pages for Franz Mittler and, in the first row of the concert hall were many of the guests from our hotel. You can imagine how they all wanted to know the next day “How come?” and “Who are you?” and so on. Anyway, I even had a newspaper woman, who also was a friend from Vienna, who wrote an article about me because a Viennese lawyer as a concierge was unheard of in the Austria of these days.

But, having set the record straight, after the season was over and I had made a bit of money during that season, then came – and only then came — the excursion to Palestine and my eventual return, and after that return my employment at the Hotel Münchnerhof as a night concierge. You know, as I go along, I can see how difficult it must be for somebody to write his memoirs because I constantly catch myself on lapses in time. I must correct again because I’ll be damned if I start re-recording this. The night concierge thing in the Hotel Münchnerhof again came much later because I realized that between 1934 and the Anschluss in 1938 some time had passed and during that time other things happened. As a matter of fact, after the experience in Bad Ischl and my experience in Palestine there was, on the horizon, the World’s Fair in Paris in 1937. Somehow, I had managed one way or another until then, and decided that this was my chance to get out of Austria and stay out.

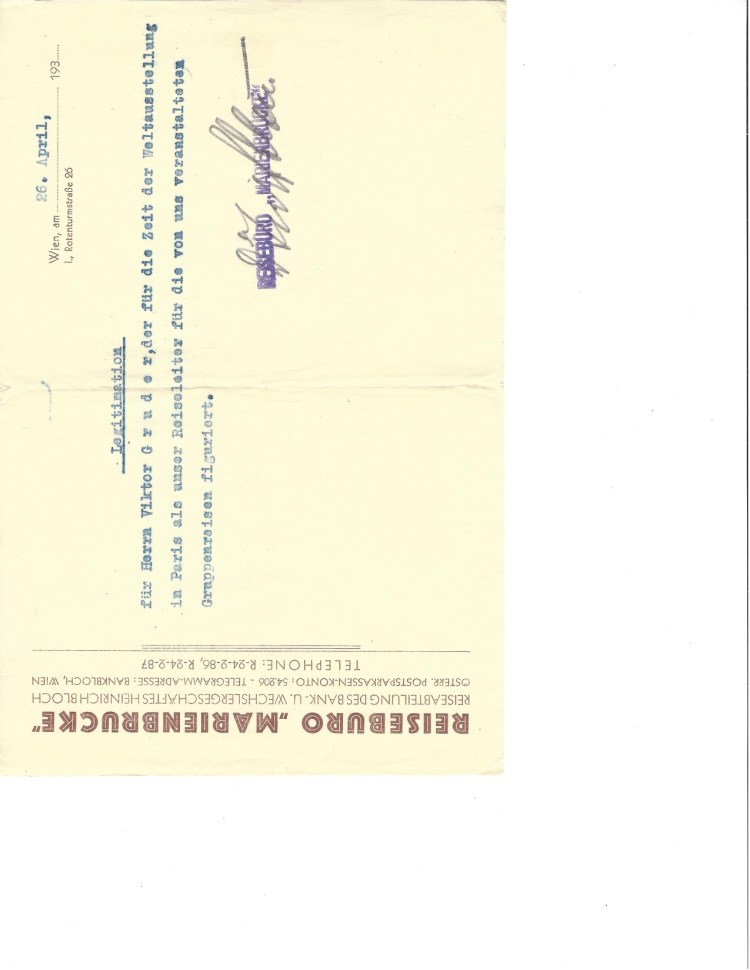

And I went to Paris with very, very little money – practically none – and was going to work at the World’s Fair. Then — I guess I had many instances of good luck in my life – a bunch of Viennese boys of about the same age as I was had created a travel agency and had hit upon the marvelous idea of a package tour to Paris.

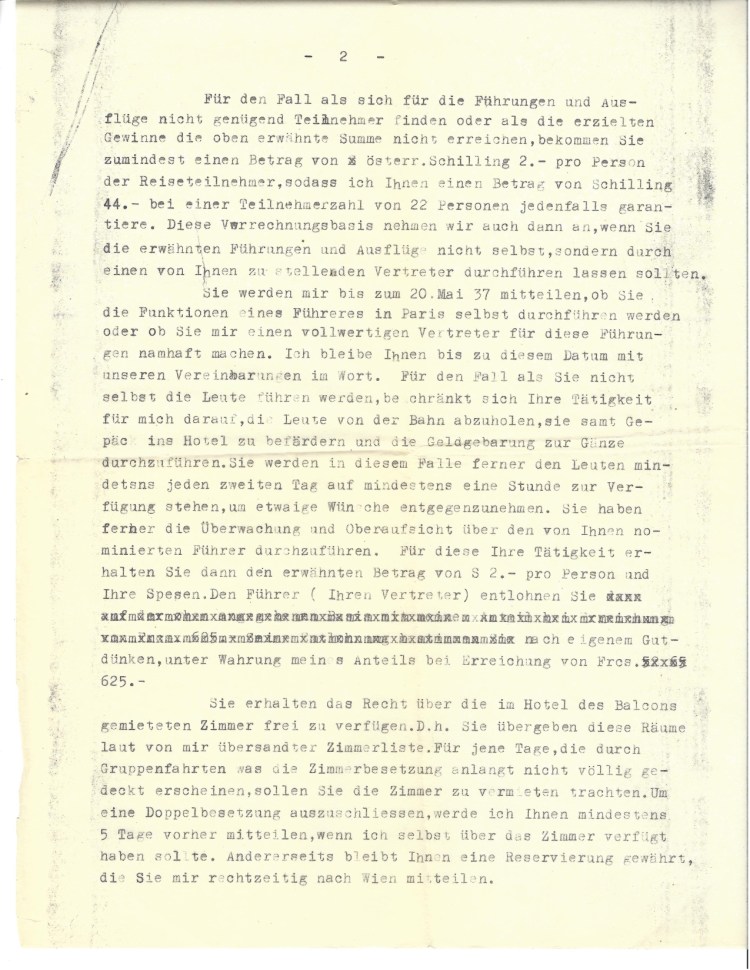

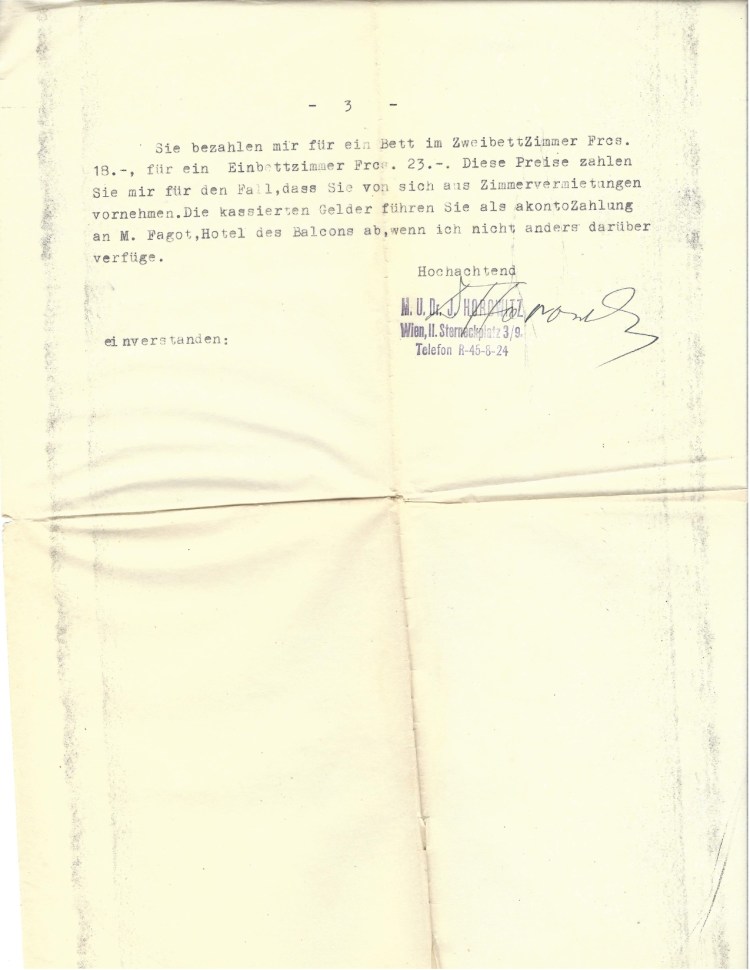

In fact, the man who had this idea was a cousin of Dicky and he went to Paris, rented a fourth-class hotel – or rather, he rented a fixed number of rooms in a fourth-class hotel, booked clients in Vienna and sent them by train to Paris to the World’s Fair. My job (and this was the basis of the agreement we made) was to pick them up in Paris, bring them to the hotel and, after a stay of a week, bring them back to the train where they either would go on to Italy for a week or go back to Vienna. And I was to get ten schillings, which was about two dollars, a head for this service. That was my savings because I couldn’t land a job at the World’s Fair. Unemployment in France was great, almost as great as Vienna and, besides, I had no work permit, so I fell back on this arrangement. Incidentally, this arrangement was interesting for the travel agency, because for every ten people they sent from the train, they got one free ticket for the guide and, sending no guide along but having me in Paris saved them the cost of a ticket, which they then cashed in. That was, I believe, the total margin of their profits.

Well, with that began a rather interesting experience. I had my first group arrive at the Gare de l’Est. It took something like close to 24 hours at the time to travel from Vienna by train to Paris. I received my group.