Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 6A, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

…….

I don’t want to be overly ambitious in this project that you have asked me to undertake. You wanted to know things about our background – our background meaning Mommy’s, mine. Things about our life before you came aboard. I find it very difficult to do this in any coherent way. I’m not a writer. I don’t know where to begin. It will have to be somewhere in the middle. Let me try this: the other day the name of a fellow Viennese refugee came up. “Viennese” means a fellow with whom I shared growing up in Vienna. A “refugee” means that he, as did Mommy and I, fled Vienna in the wake of the advent of Hitler. And it occurred to me that, somehow, most of these Viennese whom I have known either in Vienna or later did amazingly well in their newfound homes. Most of them went to the United States, but some of them went to England, to other countries and, without exception — at least without exception I can think of — all of them did rather well.

Some examples. I think you have recently met Fred Praeger.

Mommy and I knew Praeger when we served in military government in Wiesbaden a few years before you were born. He was in public affairs; I was in the legal division. Fred Praeger is the son of a Viennese publisher who specialized in Judaica. Fred was not terribly popular in Wiesbaden. He is uncouth, robust and gives the impression of bullying through, overcoming odds, people, whatever stands in his way, but with a tremendous gift for success. When he left military government, he had saved, from his salary, something slightly in excess of two thousand dollars and he told us when he gets to New York he will try to start a publishing business. Well, I won’t go into the details of it. He did found a publishing business, one in which he invented two major trends. He specialized in books dealing with Iron Curtain countries, highly specialized books like the agrarian reforms in Albania or something, books of which he knew that every U.S. university library had to have a copy. Very limited editions, but those limited editions were sold when they were printed. Then he branched out and published art books – cheap art books printed on excellent paper with very good reproductions. I think he had the reproductions made in Holland. He linked up with an English publishing firm and parlayed this into a major business – so much so that a few years later, he sold Praeger Publications, his firm, to the people who owned the Encyclopedia Britannica for a price of one million dollars. I’m using this as a sort of illustration of the point I want to make – the oddity that people who came from a background similar to mine succeeded.

Now he is only one example. Let me think of others. There is Rudy Flesch, a fellow law student with whom I shared courses at Faulhaber’s. (That was an institution where most law students went for cram courses before exams, because we law students didn’t like to go to university listening to rather dull professors lecturing.) You went to cram courses and Rudy Flesch and I were in the same course. When I caught sight of him in the United States, he had become an expert on the English language. He wrote a bestseller, “Why Johnny Can’t Read”, and, in short, Rudy Flesch is the recognized authority in the United States on the effective use of the English language. He taught Americans how to write and speak English. He was hired by a newspaper association – I forget which – to teach reporters effective use of the English language. I find that extraordinary. This is a Viennese lawyer who, incidentally, when he speaks has the accent of a Katzenjammer Kid, and he’s teaching Americans the proper use of English.

I’ll give you a few other names and then we’ll eventually, I guess, come to the point. You know Bill Ebenstein’s history. He of course didn’t only become successful in the United States. He published his first book when he was twenty, still in Vienna — itself a rather extraordinary story because he wrote on fascism in Italy and used a simple device of going as a student to a representative of the Italian fascist government in Vienna and said that he wants to make a study of fascism and write a book about it. He didn’t bother to tell them that it was going to be critical of fascism. He just made it clear that he wants to study it. They were so flattered that they opened the archives for him. When he finally completed the book, he sent it to England to two publishers and both were willing to accept it. And, rather in a dilemma, he asked my advice: how is he going to tell his father, who is hoping that his son would become a successful lawyer, that he rather would write? Well, I managed to convince him that I couldn’t conceive of a Jewish father who wouldn’t be proud of a son who was a writer. And that turns out to be correct. He accepted publication by the lesser of the two publishers in England because, although they paid less, it carried with it a year at the university in London and an introduction by Laski. He became eventually Laski’s assistant and that was pretty helpful when he emigrated to the United States, where he first started at the University of Wisconsin, then Princeton, and in the end, Santa Barbara.

Another success story was Ossi Teller [ed: Oskar Teller; see 2 February 1932 Gruder home concert picture below,] a man who, in Vienna, had to earn a living and he sold products of shell, a shell company where his wife was the secretary of the president of the Austrian branch of the company, and on the side, he studied law — eventually got his law degree. But he never did too well in Vienna financially because he was too much interested in running the Jewish cultural center and doing cabaret, Jewish political cabaret in Vienna. When he came to the States, he eventually landed a job with the National Graphic [ed: perhaps Geographic] Society and invented a new domain – a packaged museum consisting of framed reproductions which were sold as little museums to libraries all over the country, to universities and libraries which then lent them out like books so that people could take them home and learn to live with pictures on their walls. This became a major business of the company and Teller got very much recognition for his contribution to the spreading of appreciation of art in the U.S. — so much so that somebody read a laudatory mention of it into the Congressional Record. Incidentally, he is doing this now in Israel.

But it’s happened not only in the United States. In Australia, where you just visited, Richard Goldner, who was a musician in Vienna [ed: see 2 February 1932 Gruder home concert picture below,] and had a bent of mind which enabled him to invent things. I don’t exactly know what he invented besides the first invention, he made still in Vienna, which was a sordine to be fixed on a violin or viola and which could be activated by a movement of the chin. Several famous soloists adopted it. I don’t think that this ever made him rich, however, he did invent various things which did make him a rich man in Australia where he had emigrated, and he used his money to make Australia music country. He has a concert hall built – rather, a concert hall that was built was called after him. He contributed mightily in money, but most of all, he contributed this tremendous knowledge of music. You are the one who told me that you learned that he is now, at present, teaching music at the University of Washington. And there is his sister-in-law, with whom you spoke on the telephone, Lizzy [Liesl] Schreiner, who was one of the first women architect graduates in Vienna and, as I understand it, became a very prominent architect in Sydney, Australia.

Paul Löwe went to London, or rather to England. He was a lawyer in Vienna (not practicing, he had just finished the university. ) And he invented a business in England: the buying and selling of obsolete radio tubes. “Obsolete” in a sense that they had been replaced by the transistor, therefore people in less fortunate countries who still operate with radios can’t find the tubes very readily on the market. He supplied that source and became a very rich man in doing that. I ran into a Viennese of the same background and in an American industry. Fred Adler is one of the vice presidents of Uze aircraft and holds something like sixty patents of things he invented in the aerospace industry. Erik Levy is a Viennese who is a vice president in Raytheon, somewhat operating in a similar field as Fred Adler.

The reason why I’m telling you all this is because I want to make a point. It strikes me as a phenomenon which needs an explanation and a possible explanation, at least one that satisfies me, is that in an attempt to find out what all these people have in common, I only arrive at two or three traits. We all belong to a group of people who came to our various new homes with a more or less completed education, and an education of a quality which was apparently either equal or perhaps in some cases better than that of the people with whom we competed in the countries to which we went. That is one thing, however that doesn’t alone explain it. (Incidentally, it was the first wave of immigrants to the United States that came with a large number of educated people. That wasn’t the case in the Irish potato famine immigration wave. It wasn’t the case for the Germans who fled the Bismarck anti-socialist laws and surely wasn’t the case for the various waves of Italians and Greeks who came simply for economic reasons.)

Now, another thing that struck me as a possible cause for trying harder is the fact that we all had to prove something. We belonged to a generation of openly persecuted people, and we aspired to a life which we could have expected to lead in Vienna had we stayed there, and things would have been normal – that is, no Hitler persecution — the life of a bourgeois middle class with a liberal outlook and politically interested but not necessarily engagé. Such a life, the circle in which I grew up, included a complete absence of Jewish awareness. Yes, of course, we were Jewish, not practicing and we didn’t take particular interest in the question of whether somebody was Jewish or not. Several instances where this came to light: when Hitler grew in Germany, then people started wondering who among one’s friends or acquaintances was Jewish; and that in Vienna the interest in establishing one’s own Jewishness or that of other came to the fore only when it was caused by political events which foreshadowed their impact on our own future.

My home, for instance, was that of a militant social democrat. My father was extremely active in the Social Democratic Party, when it was in its infancy in Austria. He participated in the Revolution of 1918, which culminated in chasing away the Hapsburgs and in a socialist president and at first even a socialist government which didn’t last long. My father remained active in this field, and it was very interesting how I myself developed. I grew up in this atmosphere surrounded by the friends of my parents who all felt as he did; but when I was old enough to think, it struck me that this had become a rather bourgeois party and I didn’t feel particularly attracted because it seemed that their major demands had been met. There was social security, a 48-hour week (which later became 40 hours,) the city of Vienna had a two-thirds social democratic majority, a genius as a city secretary for housing who invented social housing which became a model all over Europe. (Incidentally, your aunt lives in one of those houses; I realize that it’s nothing very impressive now, but it was indeed in the early thirties.) These houses were built by the city of Vienna, which is still the owner, and the rent is nominal even today. So, I found nothing particularly enticing about working for the Social Democratic Party and therefore turned my interests elsewhere.

Even in secondary school, we went a lot to the theatre, went a lot to the opera, and there I was particularly lucky. My parents had a friend (I now know that he was a homosexual. I don’t know when I realized that then, but it is totally unimportant.) He was a washed-out singer. He, at one time, had been a Wagner tenor, and he wasn’t dumb, and being a steady guest in our house – that isn’t the right word; he was one of the lame ducks that my father supported and my mother fed, regularly, four-five times a week — my father gave him money; that’s what he lived on. Apparently out of a sense of gratitude or obligation, or to cause my father to continue this, he took over my education in music and introduced me to Wagner. Now, at the age of fifteen-sixteen, you kneel into the things with an intensity which later gets lost, I’m afraid. But at the time, I really studied with him.

And so began my daily visits to the opera. Daily means that the opera, which was playing for ten months a year in Vienna, was the place where I spent my evenings. It was an exception if I dropped out an evening and went to the theater instead or saw a concert. Add to this the fact that several of my schoolmates intended to become professional musicians. And so, when I was about eighteen, which would make it 1929, we decided that the general public hears music which is geared to the tastes of the general public and therefore there are certain things which are not being played. And we hit upon the idea of arranging musical evenings where musicians would play for other musicians. Well, our apartment lent itself to it.

Perhaps this is the point at which I could describe the apartment. It looked, as you know, over the Karlsplatz. The rooms were huge and there were seven large rooms. One was at the corner of Nibelungengasse and Karlsplatz, and it was big enough to serve as a place where one could make music and have people sit around, and we had as many as a hundred and twenty people, not all in that room but in this and the two adjoining rooms together.

So, we made up certain rules which were that we would invite only musicians (that is professional musicians;) and everybody may bring somebody else provided he is also a musician; that no food would be served. (Of course, I couldn’t keep my mother from making cookies and there was coffee because this was Vienna.) And so it began. Very quickly it branched out to include not just musicians but also singers — of course, which are musicians – but also actors and, by a lucky coincidence, cabaret people. By cabaret I mean Viennese political cabaret, such as the Lorenz doing the Kommödchen. [ed: see Letter 10 “Düsseldorf” for more about Kay and Lore Lorenz and their cabaret Kommödchen.] And that came about because one of the major figures in that cabaret was a schoolmate of my father’s. Well, of course, my parents were included and eventually it included friends of friends, and the audience grew. We established that one cannot do this every week and we settled down to doing it every other Tuesday during the theater season – that means from the fall through the winter and spring, until the beginning of summer.

This was an extraordinary time because the musical evenings became an institution. There were young budding artists who tried to be invited because they hoped to further their careers. A beau cause because a few people were discovered there, as it were. One of them was a ravishingly beautiful, but extremely dumb lady. I forgot who brought her. But one of our good friends, Walter Leschititzky,

just was playing on the piano in a darkened room while Richard Goldner and I were flirting with this lovely lady, and she just accompanied what he was playing by humming and then singing, vocalizing, improvising with it and we discovered that we had a natural musical talent among us. It turned out that she took singing lessons. And one other habitué of our evenings, Dr. Kofler — who of all things had been conductor of the orchestra in the Folies Bergères in Paris and was the best teller of Jewish stories ever encountered – and he arranged for an audition with Clemens Krauss, the then-director of the Vienna opera, who hired this young lady, Maria Reining, who later became a very famous singer.

Another discovery was a chansonnière, a woman who sang Brecht and Weill and other things, and there was a man in Vienna, Bela Laszky, a composer, who was rather famous. His favorite and habitual performer died and this woman who was a friend of the man who brought her to us was recommended by one of our friends and she replaced him [ed: her name appears in Victor’s notes as one of the attendees at the 8 October 1929 gathering, the very first home concert held by the Gruders.] This lady, Grete Deditsch, became also famous and, unfortunately, the wrong way. She became the star cabaret performer under Hitler in Germany and thereby hangs an interesting tale. When Robert Isko, another one of our friends,

who was a kabarettist and a half Jew, met her in Munich one day. The talk came around – this was in the early days of Hitler, let’s say 1934 or so – they came around to talking about where she had been discovered. Our name came up and she said, “Oh yeah, such nice people. What a pity that they’re Jewish.” And then she continued and said, “I wonder whether anybody still comes to their house.”

But when Isko related this conversation to us, and our evenings were still going strong, it occurred to me for the first time, I must confess, to look over the lists I kept of various visitors throughout the years, together with who performed what, and I went through the names and discovered, to my great astonishment, that for a good forty percent of the people who came, I had no idea whether they were Jewish or not. Now this is, I believe, something that would hardly be possible in the United States today. Somehow it may never have been that way or perhaps the Hitler experience made people conscious of the fact that they were Jewish, whether they were practicing or not. In fact, it certainly made me conscious of it, although in my case another experience played a role.

You know that in 1934, when Austria was governed first by Chancellor Dollfuss, who was murdered by the Nazis (a party which he had declared illegal) and who was succeeded by Schuschnigg, both of them Christian Democrats but of a bent which the socialists and Nazis called clerico-fascism. (“Clerical” because the Catholic church played a tremendous role in it, and “fascism” because that’s what it was although in typically Austrian fashion it was despotism – gemildet durch Schlamperei [softened through sloppiness].) In order to give proper credit for the term it is either by Grillparzer or by Nestroy, two Austrian writers who applied it during the reign of the Hapsburgs.) [ed: it is generally and probably more correctly attributed to Victor Adler]. In February 1934, shortly after the big riots in Paris, there came an Aufstand [revolt. See Austrian Civil War] in Vienna. It came to a shooting match, literally, between the armed arm of the Socialists called the Schutzbund, and the military arm of the Schuschnigg regime which was called the Heimwehr. Their leader was Fürst Starhemberg and they shot it out. It was a true revolution. No, it was a true shooting match, and in a typically unrealistic fashion the socialists were rather amazed – no, not amazed, they were disappointed. They cried foul when the government, with the help of the police and the army, started shooting at the various city-owned buildings which were used as fortresses by the armed socialists. Why on earth they should have been surprised about this is beyond me, but this is with the hindsight of today. At the time, apparently, one expected that one would answer rifle fire only with rifle fire.

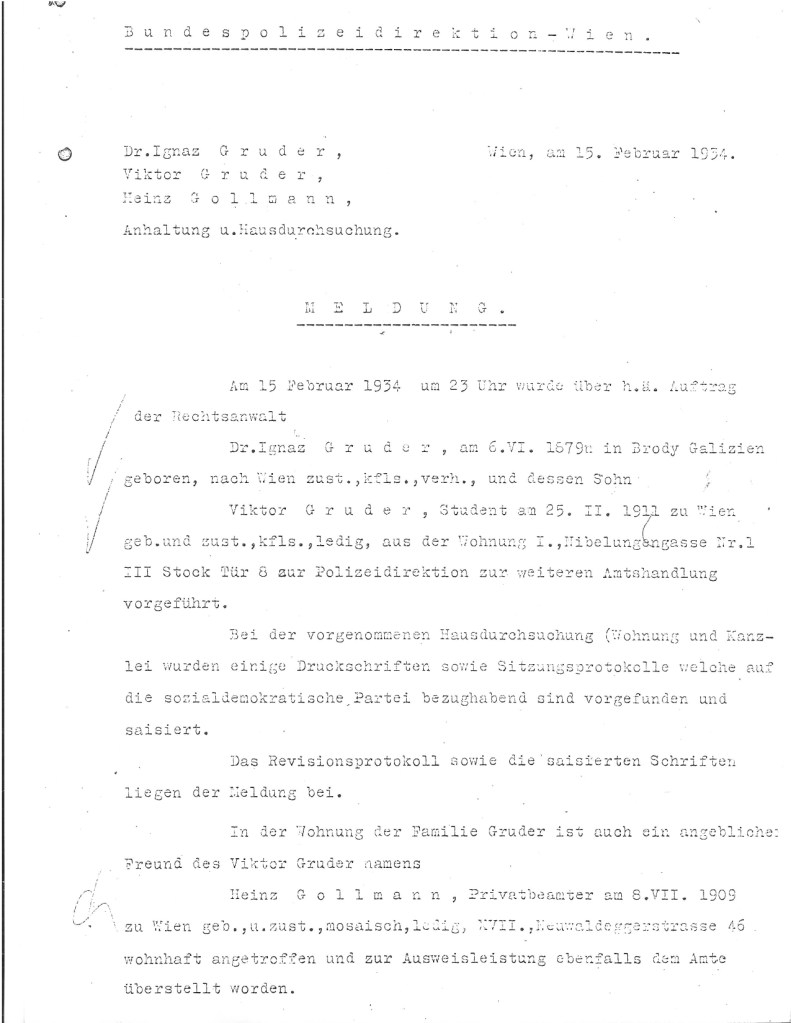

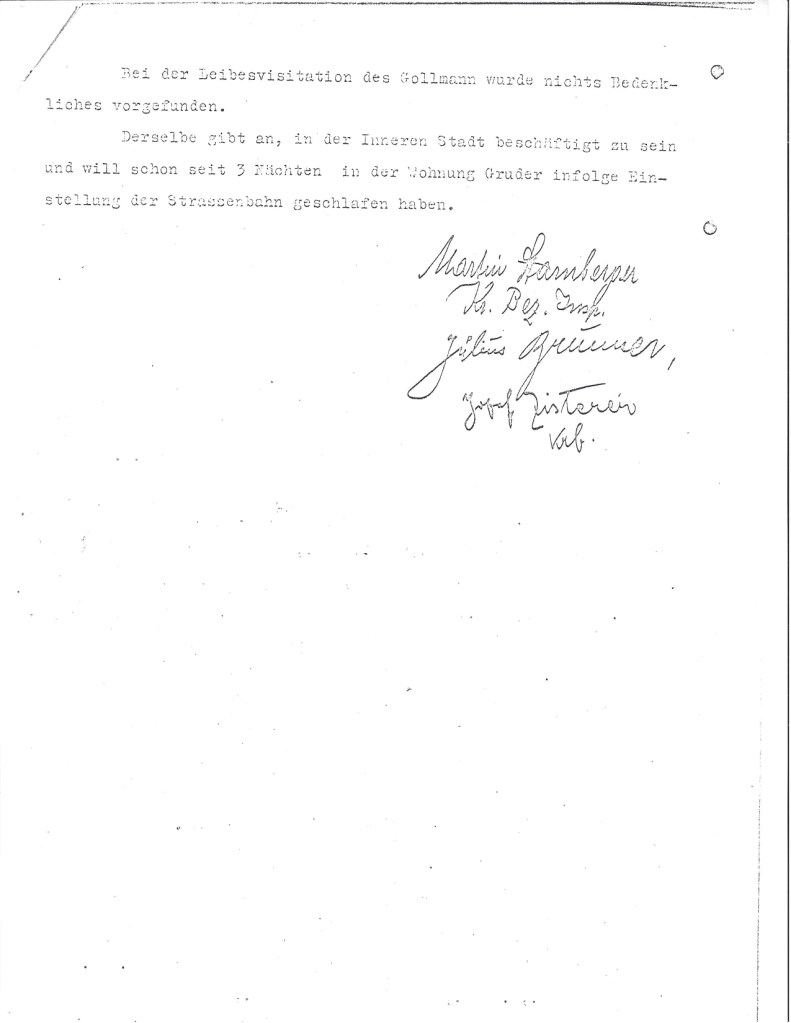

In the wake of this, or rather because of this, the government ordered the arrest of all the prominent socialist lawyers, and that included my father and some dozen or so others. And in order to make it impossible for the offices of these men to operate, the junior lawyers were arrested too, and that included myself. I came home with Heinz Gollmann, who was going to sleep over in town, and found our apartment infested with police in civilian clothes with drawn guns, who immediately frisked us and ordered us to come with them. Incidentally, it was the only time in my life where somebody pointed a loaded pistol at me and it was a baffling experience, not very pleasant. Well, they brought us to the police headquarters, which was then close to where your aunt Lydia is living, and we were thrown in a cell. Separate, incidentally.

I found myself in the same cell with the first Austrian socialist Minister of Justice, Doktor Eisler. Neither one of us were used to prison. We didn’t exactly know how one behaves there. Strangely enough, he became more frantic than I did and during the second night there he had persuaded me that not only must I allow him to commit suicide without interfering, but I have to help him. And he had me convinced that he was facing a firing squad any day now, or at least a concentration camp. Yes, they did exist already. And I must help him. He broke his glasses when I was sleeping in the cot, listening to strange noises he made, when he called out and said “Herr Kollege, ich brauche Ihre Hilfe, ich brauche Ihren anatomischen Ratschlag.” [“Colleague, I need your help, I need your anatomical advice.”] He couldn’t find his vein. Well, this almost grotesque call for help, and the manner in which it was made, brought me to my senses. I banged at the door, called for help, and they caught him and bandaged his not very badly cut arm. And ever since he credits me with having saved his life, which had not really been endangered.

This whole séjour at the police — in the police prisons was an extraordinary, surrealistic experience. The corridors — you know, we had to give up shoelaces and everybody was shuffling around without a tie and without collars. And the people around me were illustrious company. There was the mayor of Vienna, and the city treasurer, and the previously-mentioned genius who was responsible for social affairs, Professor Tandler. It was an eerie atmosphere, later very well described by Doctor Färber, a Viennese lawyer and great wit, who told me that it reminded him of the prison in “The Fledermaus,” where the Kerkermeister, the sentry, is holding his keys in one hand and the menu in the other. The menu actually existed because, since we were not convicted criminals, we had the right to order things from a nearby restaurant to improve on the not very good prison food.

And I know my father was there. I had no idea what happened to him, if he was außerdem in, enclosed, gesetzt [taken into custody.] As a matter of fact, I did not know what was going to happen to me because there was no such thing as an interrogation. Nothing happened. I tried to get used to the idea of having to go to a toilet while somebody else was in the same room, an enterprise which took both Dr. Eisler and me several days before we could learn to do it. And he always introduced his attempts by saying apologetically that he was going to, “Ich werde eine versuch machen”. [“I’m going to have a try.”] My olfactory senses then told me whether the “versuch” was successful.