Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 6B, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

……

There has been a long interruption…. I decided to continue, but before doing this I listened to what I have so far recorded. I’m not terribly happy with the result because of two factors. Not only is it not a very good recording but I sense that it may give the impression of some kind of nostalgia, particularly where I said that people in the settlement in which I lived tried to arrive at what they might have become in Vienna had everything been normal. I looked at this critically and it is absolutely not so. I for one did never intend – no, never is wrong, but starting with 1934 — did not feel that I wanted to live in Vienna even if there were no Hitler. It was a dead end. It struck me then as a city which lived on its past and that I couldn’t breathe there. The natural inborn antisemitism was known to me. I was personally a victim of it only rarely, when there were fights at the university where the Nazis (or what we later called Nazis) were beating up the Jewish students. [ed: see Bruce F. Pauley, From Prejudice to Persecution A History of Austrian Anti-Semitism, The University of North Carolina Press, 1992, particularly Chapter 9 “Segregation and Renewed Violence” for a description of the violence directed at Jewish students in Austrian universities.] But I went very rarely to the university, relying on cram courses rather.

But the whole atmosphere was one of a good deal of unemployment and I was aware of the fact that the kind of life that I led was being, living in a cocoon, that we were a very small group of people who were aisé in our lifestyle, and that didn’t apply to the masses. Yet the workers, the socialists, or those for whom the socialists fought, were — when they were organized into unions were — just as little cause or objects of particular pity because they were by no means in misery, while the unemployed, the old, of course were. And that was one of my reproaches of the Social Democrats, that the rhetoric of the days when the poor exploited worker was indeed poor and exploited, that rhetoric no longer fitted the situation. There was an unbehagen [discomfort,] a feeling of “This isn’t a county in which I can breathe.”

Now that much for whatever may have sounded nostalgic, or that I ever had any image of myself as a successful lawyer in Vienna. As a matter of fact, I didn’t particularly enjoy the practice of law. I was interested in political science. That’s the only exam in which I had a very good note. While the practice of law, you know, fighting for one client who has some money coming from another client, didn’t particularly send me. The practice of criminal law is ninety-nine percent dull drudgery, and the remaining percent is histrionics. It has very little to do with saving a poor innocent from the gallows. Although I must say that the practice of my father was concentrating in the field of criminal justice, on the defense of political clients – that is, people who were accused of, by the government, of being underground socialists — and this is by the way how it came about that we, my father, (and I was only assisting,) defended Bruno Kreisky, the now so amazingly successful chancellor of Austria, who was then an idealistic and very effective young socialist who had been caught and my father obtained his acquittal which was celebrated as a great victory. [ed: see Biography “Nazism and WWII” for some specification on this point.]

Now I’d like to add something to the chapter of why were refugees, on the whole, rather successful in other countries. I believe I haven’t mentioned what I consider to be the main point. I only said they had to try harder, not in order to get somewhere but, and not only in order to prove something but, simply because I’m convinced that adversity is a tremendous stimulant to people who have any sense of drive. And also, we all were aware that only by pure luck and chance were we among the minority, that is the survivors. There is a sense of a mixture of being lucky – that there, but for the grace of God, go I – a relief that you are alive and a mild sense — no, not mild, but perhaps subconscious sense — of guilt of having survived where others died. And that is a tremendous stimulus. I believe it became evident when the war broke out and we were in the army. A Viennese Jew, you didn’t associate a Viennese Jew with anything but a coffeehouse and certainly not with the handling of a gun. Yet all the Jews, refugee Jews, that I knew in the army had medals for marksmanship. We simply tried harder and, when you try, it’s no particular “kunstschtück” to shoot well.

Also, that was our war; if anybody had a stake in it, we did. And this leads to another conclusion which I made much later. When we returned, we found that we had changed. “We” means all those people that I knew in the army and later met again. We had one thing in common – no, several things in common. We no longer felt as former Austrians. We had become Americans. It was no longer unnatural to say “we” and that meant Americans. And the fact that when you belong to a victorious army and when you have seen the people you fought lose, you saw them as prisoners, you saw them as civilians in bombed-out houses, you saw them beat, there is a certain sense of, well, the ressentiment has been absorbed. For having beaten them and you were part of it. And you did it with a gun in your hand, whether you shot or not. And I realized to what degree this was true, because when I spoke to people in New York or elsewhere in the States who had not been to the front, who had not been in the army, their ressentiment against Germans as a whole never ceased. I say never; I know people today who seem most uncomfortable about even visiting Germany or who do not feel comfortable in the presence of a German who is today thirty years old and obviously had nothing to do with Nazism.

Now that much was postscriptum to what I have previously recorded. And I must somewhat change what I initially intended to tell you now. You are interested in our lives, that is Mommy’s and mine. But, due to the circumstances which brought Mommy to Washington and gave you both an opportunity to talk as you haven’t been able to talk during the last seventeen years, I presume that you got a good deal of Mommy’s story from herself and perhaps I would be repeating myself if I covered the same grounds. So let me tell you perhaps a little bit about my war experiences.

Mommy might have told you about my father and how my father came to the States, which is a story in itself. But you do know that he was a human wreck when he arrived. He was a very sick man and was completely dependent on us. That would have meant that I could have gotten a deferment. I did not have to go into the army when I did but, as I said before, if it was anybody’s war, it was mine and people like me, and I just didn’t want to ask for a deferment. It was not a matter of heroism or anything. It’s just, how can I expect innocent, blue-eyed, corn-fed Americans to fight this war while I’m making money in New York? (Not that I made that much but, had I stayed as others did, I probably would have.) So, it was as a matter of course that I would go. And I was called and did go.

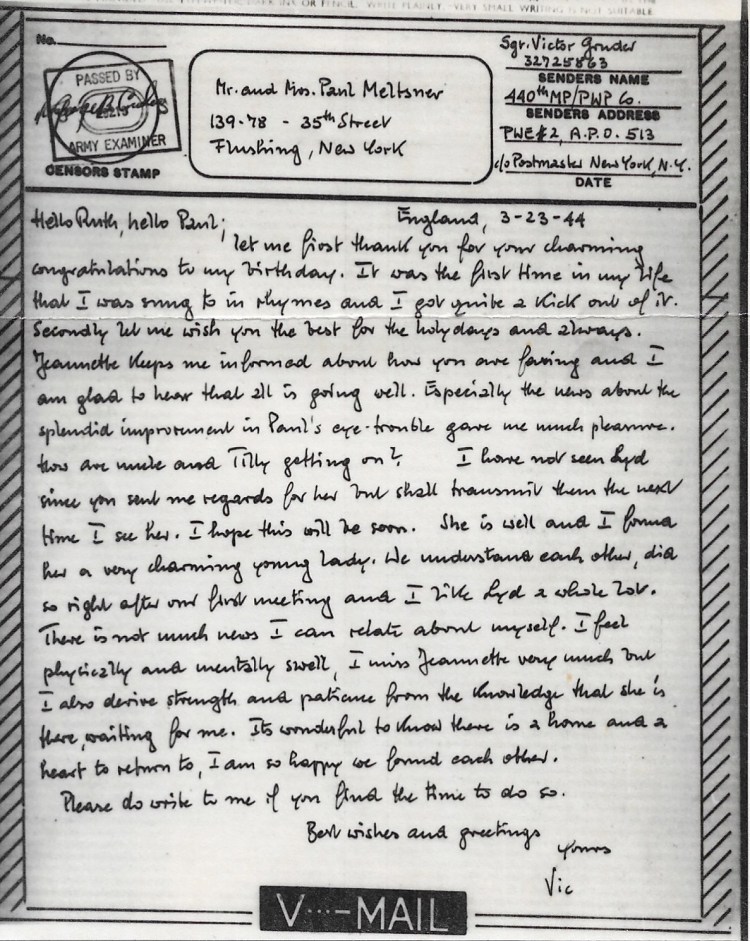

I wrote rather enthusiastic letters during my basic training, letters in which I expressed my admiration for the manner in which civilians who never had handled a gun were in an exceedingly short time turned into soldiers, apparently fairly good soldiers because, after all, we did win the war. (Now, as a matter of fact, my enthusiastic letters were such that Bill Ebenstein felt it necessary to send one to the New York Times for publishing.

Only to underscore that I was indeed not cynical in my assessment of the U.S. participation in that war and felt, with all other Europeans, which I still was, still am, that America had to enter the war and was glad that it did.)

After basic training, which I received – of all places – in Arkansas, where incidentally I also received my naturalization papers (somewhat earlier than one would have normally received them because when you were a soldier in the army, you could get them earlier. And so, I am naturalized in Little Rock, Arkansas, of all places.) And, towards the end of our training, we were sort of separated into some companies where the people had a higher IQ – where the average was fairly high IQ – and another company where the IQ was particularly low. And then there came a man from Washington – we were terribly impressed, he was all of a major and we had never seen anything more than a lieutenant, and a captain at that – and he told us that he was screening people for a very hush-hush project for which they need people with European backgrounds, language skills. In short, we found ourselves in a group for an aptitude test where I believe there were something like a hundred, a hundred and fifty people, among them George Herald (so that was the beginning of our friendship,) Klaus Mann (the son of Thomas Mann,) and people less illustrious like myself, and we were tested for God knows what. An interesting thing was the amount that — if we were a hundred and fifty people, there must have been something like a hundred and eighty doktor degrees present. Now the man gave us all a pep talk, told us, those of us who are above a certain level would be selected and, since the project has not yet been approved, we would be kept together in a temporary assignment, and we would hear from Washington. But that, as usual, was the last we heard of it.

We went indeed together into a company which was a quarter master depot company. Our language skills were apparently needed, even though temporarily, to label tomato juice into several languages or what have you. And we were led by a magnificent leader. He was a very ambitious captain. I believe he was in peacetime a garage owner or something like this and had the ambition to become major. So, he had the brilliant idea of volunteering the quarter master company to be attached to the parachuters because somebody has to be able to throw supplies from planes to the parachuters and we were to be the company to do that. And so, people like George Herald and myself found ourselves in training with the paratroopers. At that time all the paratroopers were volunteers and were gung-ho tremendous athletes and what have you. The regime was that in any paratrooper camp you didn’t walk, you ran on the double, even to the toilet, whether you had to or not. (I mean, whether you had to run or not!) It was a pretty tough training because being part of it we had to go over obstacle courses and do a lot of things which had not been sung at our cradle. And we learned how to load jeeps into gliders, how to throw loads out of an airplane. The door is opened, and the drop master decides when to push the button for the bomb bay to open and throw down supplies (they were supplies instead of bombs,) and I was elected a drop master and was persuaded not to be afraid of standing in the open door of an airplane because the slip stream would drive me inside of the plane – into the plane — rather than pulling me out. I only learned much later that the opposite was true but while it lasted, I didn’t fall out, miraculously.

And so, we were sent to, I believe, eleven different camps, learning various arts connected with parachuting such as holding your own parachute (which we were not allowed to wear because it would have been in the way. It doesn’t serve any purpose in a low flying plane because it doesn’t have time to be deployed and besides it’s in the way if you try to get big heavy bundles out of an airplane and drop it within something like five seconds while you’re over the target area.) Well, it was a rather athletic experience and George Herald and I, once in the camp, decided, “what on earth are we doing here? This is really not exactly where our talents lie.” And so George decided we’d go and ask for a transfer and we went into the personnel office of that huge camp in Fort Bragg and then George pushed me forward and said, “you talk,” so what I told the sergeant who was just about to pack up and go home that we were both, given something of our background, of our education, and that we have a feeling that we are slightly ill-assigned, poorly assigned, and the sergeant apparently felt rather impressed with all this, dropped his packages and stayed with us and asked us to fill out an application immediately – which we did. And he said we would hear.

Then we went on maneuvers which were held at the joining of – what was it? — Tennessee and Kentucky. 120 degrees in the shade and we lived in tents outside Camp Breckinridge and proved highly uncomfortable, particularly one night when a bug crawled into my ear and I started screaming so that George thought — with whom I shared a tent, George Herald — that I had gone crazy. And, eventually, I didn’t get it out; it injured my eardrum. But it was a terrible experience and ever since, I shudder at the thought of picnics or voluntarily spending a night in a tent. What an idea. But we were sitting there and at one time we were waiting between one phase of the maneuvers which had ended and the next phase, which was to start a week later, and we did pretty much nothing but exercise and in the evening, we had the right to crawl in through the barbed wire into Camp Breckinridge. We showered and then went to the enlisted men’s club. In that club, there were volunteer ladies. One lady, who was then about in her sixties, asked me one day a personal question that had something to do with playing piano and she was interested in what I was playing, and we got to talking and she invited me to their house, which turned out to be one of the great mansions in Hopkinsville, Kentucky. And living with them in that house was the commanding general of Camp Breckinridge, a major general. And she had invited me, and I had mentioned George, both of us, to come to their house because she felt that people with such, to her, impressive credentials of education should be used in a better way by the army, and she wanted the general to hear our story.

So, George and I spruced ourselves up and very excited, first time in our army life that we would face a live general except only in pictures for us, and we arrived at the house. No, no – before that, we showered, and we were discussing while we were in the shower (these were huge showers for many people. We were alone there. We thought we were,) and we were discussing how one deals with the general — do you salute him when you meet him in a private home? Do you keep on addressing him as “General”? Do you stand at attention, what do you do? And George and I were discussing that. Well, then we were dressed, we cleaned our shoes and our pants and went to the house and the general was most gracious. He shook our hands, no saluting. We had a very wonderful evening, had a very good dinner and very much buoyed by this experience, we crawled back into our tent area — went out from the camp, back through the barbed wire – when we were challenged by a guard from own company who sounded awfully official and said “You two guys have been reported AWOL (absent without leave). When there was an alert, the roll was called, and you weren’t there.” So, we called the sergeant. The sergeant called the officer, the duty officer. “And where were you?” I said, “we were in the camp. As a matter of fact, we were with General Peckham.” “You were what?” “We were the guests of General Peckham.” Well, he scratched his head and reported this to that idiotic captain or ambitious captain. And that captain was never quite sure whether we were pulling his leg or not; we were a puzzle to him. I’ll come back to this but, at any rate, we weren’t made like the others, and he didn’t know what to believe so apparently, he called the General who confirmed that we had been with him, so that’s the last we heard of it. Only days later it occurred to us to ask what the alert was about, and they told us that next to Camp Breckinridge was a stockade of German prisoners of war and two of them had escaped. As a matter of fact, they had been overheard talking with a very strong German accent in the shower room. Well, George and I kept our mouths shut and we never let onto the fact that the two German escaped prisoners must have been us.

Well anyway, that captain was very much puzzled by us at other occasions. He, being a very good athlete, insisted that any free time that had to be used somehow (because in the army the principle is that you’ve got to keep the soldiers busy, you keep them painting things or picking up bricks from a road and putting them somewhere else, and some idiotic things like that,) but this man insisted sports had to be engaged in and he ordered baseball to be played. Well, George and I stood and watched. So there came an order, apparently, down the line from the captain, who told the lieutenant, who told the sergeant, who told the corporal to ask these two men why don’t they play? We answered to the corporal, “Sorry, but we don’t know how.” Well, he went back via sergeant, lieutenant. This lieutenant hated the guts of that captain and gleefully told him that we don’t know how. That captain didn’t believe it. He sent him back. “Everybody knows how to play baseball.” I said, “We were not born in this country and where we come from people play soccer. We know that game but this game we don’t know.” But this time the captain had come himself and again, not quite sure whether we were pulling his leg, he was not going to have two goldbricks stand there and just watch the game. And he made the Solomonic decision: alright, you two guys will be umpires. So help me, I’m not inventing this story.

Well, after we survived the maneuvers, we returned, almost accidentally, to Fort Bragg and I went in for a Coca-Cola and there I was spied by the sergeant who had taken our applications and said, “For God’s sake, where have you fellows been? We have been looking for you all over because we have a transfer for you, your transfer to military government school as teachers, of military government, and you are going to go to Leavenworth.” In this case Leavenworth was also a military stockade but we were not sent to the stockade but to the school. Now we were tremendously elated by this, packed our things and enjoyed the idea that the captain would lose his two targets and proceeded to a new camp where we were received by a twenty-three-year-old lieutenant and a master sergeant by the name of Feldman, a Jew from New York, and the lieutenant looked over our papers. (Incidentally, our orders read “Report to the commanding general,” so we thought we were gonna report to the commanding general, never having seen a military order before and not knowing that every military order orders you to report to the commanding general whom you never get to see. You are being received by a lieutenant.)

Well, the lieutenant looked over our, well let’s say, CV, and said, “You guys speak German?” “Yes.” “And you guys can type?” “Yes.” “Sergeant Feldman, test these guys speaking German, test the German of these guys.” Sergeant Feldman, who didn’t speak a word of German, spoke Yiddish and addressed us in Yiddish. We answered with a yes and no. After a while, ist mir das zu blöd geworden,[I found this too silly] I told him, “Look, this is a graduate of the university in Basel and I’m a graduate of the University of Vienna; it’s our mother tongue.” Whereupon Sergeant Feldman turned to the lieutenant and said, “Them guys speak better German than I do.” And that was the end of our assignment to the military government school because the lieutenant found two victims and assigned us to a prisoner of war processing company. These were people who were intended to function, to interrogate German prisoners, and it was a company on alert — that meant, ready for shipment overseas. That also meant that you could no longer be transferred out of it. We went to the chaplain. We went to the head of the military government school and said look, we were sent here as teachers to finally do something. We are skillful. But there was a rule that couldn’t be altered, a right of company: we had to go! And so, we were now practicing front line duties for going overseas. We didn’t know – Europe, Japan — we didn’t know.

At that time, during one of the obstacle courses, George injured his knee. It was a revival of an old injury he had suffered when he was in the Foreign Legion. Yes, George, who had been a refugee in Paris, had volunteered for the Foreign Legion and that was great misery for him because George is blessed with two left hands, who cannot handle a gun if his life depended on it. And since it said on his papers that he was in the famous Foreign Legion he was the butt of very much fun-making and every time he did something wrong there was great hilarity. And that he fell off the truck somewhere in Algiers caused him a knee injury which then revived on that obstacle course and George was in the hospital and tells me long speeches that some Jewish doctor there wanted to give him a medical discharge and he doesn’t want that because it’s his war and he has to fight it and he doesn’t want to leave the army, and I had a hell of a time persuading him that as a journalist he would do a greater contribution, make a greater contribution, than as an inept soldier. Eventually I was able to persuade him. George was released from the hospital on medical release and, three weeks later, with a rank of — as a civilian foreign correspondent with a rank of major (he was a private in the army) he was sent to London where he worked for the War Information Office. And incidentally, much later, one day on the street he saw the man, our former captain (the umpire guy) who had meanwhile made major and George took great pleasure in the fact that he now ranked him and, very condescendingly, patted him on the shoulder and said, “Oh, hello, Toplin[? Toffler? Tofflin?].” Now that much for George. [ed: George Herald went on to have an important career as a journalist, including covering the Nuremberg trials.]

I went overseas with this company. We went to Bristol, waiting for D-Day, for the invasion, and I was absolutely disgusted with the stupid and uninteresting work I had to do and asked for a transfer to some more involved company or outfit and was transferred to what? To the provost marshal. Now that at least had something vaguely to do with the law and in the provost marshal’s office I discovered that we were going to be the forward support headquarters for what later was going to be the First Army which made the landing and the breakthrough in France.

Anyway D-Day came when we were in Bristol, lodged in private houses in sort of a lower middle-class neighborhood in Bristol and we embarked — not on invasion day, it was D+3. And that is probably an experience which I find hard to forget because the sight, as far as the eye could reach, of ships going towards France. Hundreds, hundreds of ships; thousands, ten thousands of soldiers. You hear the distant thunder of guns and, in the back of you, you hear the V-2 bombs falling on England. It’s an eerie feeling. But somehow you feel like in the stillness of the middle of the eye of a hurricane. Absolutely still around you. I guess partly fear, partly excitement. I don’t know how the hours passed.

I do know that I rode off that landing boat onto the beach in a jeep which I drove. On French soil now, I was directed by an MP who told me to go “thataway” and then I was posted there, and I shall tell the others to go “thataway.” Well, I did find myself, all by myself, in the middle of a French field in Normandy, peaceful as anything, cow bells ringing gently in the air, beautiful sky in June, lovely day, not a soul anywhere, no guns – oh yes, in the far distance, some artillery thunder. And then I see an incredible sight: a Normandy peasant in a blue smock, gray hair, red cheeks, huge man carrying two milk cans, walking towards me. Well, I am terribly ému [moved, emotional] at the first Frenchman I see and I pump his hand, we shake hands, we embrace, and I am holding him a speech in French in which I tell him all about the tremendous emotion I feel about being on French soil which is now going to be liberated, and “Vive la France” and “Vive l’Amérique” and all this goes on for at least three minutes of speech making, me practically choking up with emotion and he constantly pumping my hand while this is going on, and finally he tells me, “Je suis dur d’oreille” [hard of hearing.] I have never made a patriotic speech since.

There then followed a period which has a Kafkaesque sort of incongruity to it. Picture this: the beaches had been secured by the time we got there. It was a kind of beachhead where we were, a strip of land between the sea and the highway from Cherbourg to the center of France. Beyond that highway were such places as St. Lô and, behind St. Lô, slightly elevated (St. Lô is slightly elevated,) was the German artillery. They had dug in there and the U.S. forces (I later learned) had to gather the necessary equipment to make what later became known as The Breakthrough at St. Lô. In the meantime, there were something like 600,000 American soldiers just on the strip around Ste. Mère Eglise, somewhat an area from halfway from Cherbourg to Ste. Mère Eglise, Isigny, and halfway towards Bayeux. Below Bayeux you had the same situation with the British soldiers sitting there. And it was a most peaceful time. Nothing happened whatsoever. Every night we lived in tents, surrounded by the hedge rows, which are typical for Normandy. We had work tents in which we set up typewriters because we were a headquarters and we were supposed to process and arrange for the masses of German prisoners we were to receive, which were going to be sent back by the hopefully victorious First Army.

Now the Front was all of three and a half kilometers away from us. That’s not very far as, not as the birds but the obus [bombs] fly, and yet they had trained their guns on the Cherbourg highway and the German Gründlichkeit, they hit that highway with absolute clocklike regularity — so much that you could figure out the time when you could dash between the shots. They never shot short or wide. It was apparently not done by any observer, but it had been preset that way and the Germans never departed from it. So not much damage was done and a hell of a lot of traffic, an incredible amount of equipment, moved on that highway. They never knew that we built a little detour to overcome the fact that they had knocked out one bridge and they kept on hitting that bridge. In other words, the superb German war machine made exactly as many blunders as any other army did, our own included.

And every night when we returned to our tents to sleep, at ten o’clock, there came a German observation plane, unarmed, flying fairly low, and the whole beach, thousands of guns opened up on him. The tracer bullets, a beautiful spectacle, you know, — green, red tracer bullets, white. It looked like fireworks. And nobody ever hit him. And we called him Bed-Check Charlie because he came with regularity at ten o’clock at night. Throughout this time (that is something like three and a half weeks,) while our headquarters was in this location, I did not see any German airplane except for Bed-Check Charlie. I understand that at one time when I was on duty to sort out some problems in the prison camp, that there was a single hit in the area where we bivouacked but otherwise it was probably the safest time I had since England because in London, Bristol, and Southampton, where we embarked, you had to duck the V-2 bombs which came down with tremendous attacks and pernicious attacks. It was the safest time I ever had.

Now then came the Breakthrough in St. Lô. [ed: see Operation Cobra.] Our army proceeded and the Germans really were now on the run, and we started to get thousands and thousands of prisoners. And I say “we.” There was a process. It was rather well organized into camps that had been prepared. In the headquarters where I worked, we sort of organized it — how many prisoners to expect the next day and to ship those who were already there out so that there would be room for them. Sort of a logistic problem we worked out.

And then came an unforgettable experience. The First Army had captured a huge German outfit, something like 50,000 people (50,000 men) [ed: this may refer to the action to close the “Falaise Gap” that ended on 22 August 1944 with the capture of an estimated 40,000 to 50,000 German soldiers.) under the command of a German major general who had surrendered himself and the troops and who, in accordance with the Convention, insisted that he must be interviewed only by a general officer. And the only general officer who had time to do that was the provost marshal for whom I worked, an American two-star general who in private life was a police chief in Minneapolis or some place. A very nice elderly gentleman who always waved you off when you tried to come to attention and all this military nonsense left him cold. His driver called him Daddy, he was a very sweet man, very nice, and this was going to be not only mine but also his first German general. And let me give you the setting: our general, Holland [ed: probably Brigadier General Thomas Leroy Holland], was seated in the school room, that is the school of Ste. Mère Eglise. It’s a one room affair in which he had his office and then there was a company clerk who kept one footlocker with files. The company clerk was a Romanian Jew by the name of Wolf Salzman, who looked a little bit like the way that the Nazis wanted Jews to look – he looked as the Germans imagined a Jew has to look.