Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 11A, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

………….

Before going on with my story, I have to go back and make a footnote to what, I think, is an important and interesting historical event I had earlier reported. Remember, I told you that after Germany was overrun, prisoners were released, displaced persons flooded the country. I talked about what I thought was a, one shameful episode in which Russian refugees were sent back to Russia. I don’t believe I used the term “refugees” at the time. They were Russian forced labor, forced by the Germans, used like other forced labor to build the Atlantic Wall, the autobahns, and I didn’t really know, I said to you that I didn’t know much about it except that the Allies sent them back to Russia and that they were all shot on the orders of Stalin.

Well, I have since learned how this came about, that it was one of the demands that Stalin made of Churchill and Roosevelt during the Yalta Conference and Roosevelt agreed to this. I don’t know any more. It was a bargaining session. I don’t know whether Roosevelt was too idealistic or too naïve to realize what would happen to these people, whether he was so anxious to get his own boys home and finished with the war that he couldn’t care less. Whatever. It was agreed in Yalta that those people would be sent back to Russia and afterwards this was carried out.

My source for this is no less than Averell Harriman. I heard him say this on French television during a program on Roosevelt. And he was, as we know, a very close advisor of Roosevelt. Needless to say that he was a great admirer of him, and it is Harriman who said that this was the shameful thing that was done in Yalta and, in his mind, the only thing for which Roosevelt deserved blame and criticism for having agreed to this – this, in connection with the fact that much controversy has gone on over Yalta and there’s a school of thought that in Yalta the world was divided into spheres of interest, into superpowers, and that a lot of trouble stemmed from that. Well, Harriman is not of that opinion. He believes that what caused the world to be divided into two camps was the fact that Stalin violated all agreements that were made in Yalta. Within days after the meeting, he just didn’t give a damn about these agreements and proceeded to do what he wanted to do, and that was the occupation of Eastern Europe, while the Western Allies stuck to their agreed positions which included letting the Russians get to Prague and to Berlin before the Western Allies did, although very easily – and that is historically established – the Western Allies would, in both cases, would have been there first had it not been the agreed position not to do so. Whether holding back the troops was Eisenhower’s decision — or not to go beyond the Elbe — whether that was Eisenhower’s own decision, or on the orders of Roosevelt and against the wish of Eisenhower, that has not been established.

Now after this little footnote (and, by the way, footnotes we didn’t have yet,) let me make another nachtrag – that’s cheating because nachtrag means nothing but postscriptum – we had, both in Düsseldorf and later in Paris, our dogs with us and I haven’t even spoken how we acquired our dogs. I haven’t mentioned that. Well, as Mommy is fond of telling, that she knew that I was, I always desired to have a dog and I’d been speaking particularly about a dackel [ed: dachshund]. I had a dog in Vienna. It was a, it was as much of a German Shepherd as Graupi was a dackel but I loved that dog very much and I wanted one. And Mommy wanted me to come back from the war hale and well, and she wrote me once in a letter, “Well, if you come back and all goes well, you can have your dog.” Well, I had long forgotten about this and there was no way of having a dog in New York, and then in Germany, not long after Mommy and my father arrived, I was sick in bed — some minor throat thing or something, but sick in bed — and I believe it was my birthday. So, it was definitely in the winter when Mommy came home with two puppies. They had been sold to her by a — given in for choice by a — kennel that swore up and down that these were rauer haardackel and I was to choose one or the other.

Well, of course, needless to say, how cute they are at that time. They were placed on the blanket. And the choosing was not done by me, but by Graupi because she immediately proceeded to climb under the blanket and to warm herself against my body. So, that was it.

The other one was taken by my colleague Tony Crea, and so both dogs got selected. Of course, you know yourself that Graupi did not grow up into a pure bred rough-haired dackel but we loved her just the same or perhaps even more. And she had puppies just at the time when in Bad Schwalbach – which would make it 1948 – we moved from the smaller house into that nice little chalet we had, and the discovery that she had finally given birth was made when Lenchen and Mommy discovered that: where is the dog? We ran after her since she wasn’t there so, returning to the former house (we were in the process of moving) looked everywhere, and there, on Lenchen’s bed in the middle of it was Graupi with her new, I believe she had six or seven, puppies, and we kept one of them. That was Dinah.

When we first got Graupi we were advised by the vet not to take her out in the cold street; she was born in the winter. And, it would mean not in bad weather, and not into the snow. So Graupi was trained, was housebroken, to do her little business in the bathroom. There was a hole, and the water could get out. That she learned, and she became very good at it, so much so that when spring came around and we took her along on an automobile trip through the forest (I think we’d been to Baden or somewhere, a long trip, we were hours and hours,) and poor Graupi couldn’t be persuaded to do her business in the woods. When we, finally, after hours returned home, she raced to the apartment door and jumped up and down, waited with bated breath to get in, and streaked for the bathroom where she then relieved herself with all signs of beatitude in her face.

Dinah in turn lost her virginity in Düsseldorf and that came about in the following way. You know that Dinah looked much more like the rough-haired dackel is supposed to look, much lower, and she didn’t have the albino eyes of Graupi. And a lady had seen Mommy with the dog on the street, accosted her, told her that she had a male dackel – or perhaps she even had it with her – and that he was very much in need of a proper wife, and we knew that Dinah also needed to have her puppies. So, the women agreed that between the eleventh and the thirteenth day of Dinah’s fertility cycle, the lady would come to our house in Lilienstrasse with her dog. And I ask you to picture the following: there is a very elegant German matron, dressed to kill, with hat and all, gloves, bringing her dog, and Mommy, equally dressed, without hat, serving her tea, very elegant, very comme it faut. And the two dogs are put out in the garden to get acquainted and let nature take its course. But the male dackel was a real one, he was very low, with very short legs, and he raced after Dinah who was much taller and could run faster. And she didn’t know what –I don’t know whether she knew or didn’t want it — anyway, she ran away from him, and he ran after her. And both the dog mothers, while conversing, making small talk with each other, in the corner of their eyes they watched whether the dogs, whether this wedding came to fruition or not. They noticed that the poor male had the tongue hanging out from all that running, and was at the point of giving up, and it wouldn’t work because Dinah was too high for him.

So, Mommy proceeded to call the vet and asked for advice on what to do. Well, the first thing the vet did was he had a very good laugh at the story. Then he assured Mommy that nature would find its way, but if they want to help, they should dig a little hole in the garden and put Dinah’s hind legs in the hole, thus bringing her to her male partner’s level. And these two ladies, both rather formally dressed, proceeded to the garden to dig a hole and to encourage their canine children. And in the next garden there was an old gardener; they hadn’t noticed him. But at one time they noticed that he was standing, leaning on his shovel, with his chin on the shovel, just watching these crazy women, and he sort of shook his head. He didn’t laugh but he shook his head in, perhaps, disapproval, or wonder, I guess?

Anyway, whether Dinah’s children were fathered by this dog is more than doubtful because in that case, they would have looked more like the real thing. I believe that one time when she got loose and ran away – you know, female dogs when in heat will do that – that some other dog must have gotten at her because half of her litter were dark and didn’t resemble anything like a dackel. Poor Dinah.

Now back to Paris. I spoke about our friends. I failed to mention that Murray Marker also got an assignment to Paris. He had returned to the States, was assigned to Paris, also to the Marshall Plan. And it was a short assignment because shortly after, no, a few months after, their arrival, elections in the States came and Eisenhower was elected President. That meant that the Republicans who hadn’t been in power throughout that whole Roosevelt and Truman time, they wanted to have a place in the sun for their party workers. They wanted posts and so it came about that Mr. Harold Stassen (you know, that lunatic who is always running for president since, he is now somewhere around ninety and still running; he was originally a governor of Minnesota, I believe, some state like that, and Stassen was a very active Republican politician at the time,) and he was appointed as the new –this is after January, what are we, 1952 — he became a member of the cabinet and was appointed as the head of the Marshall Plan agency with a congressional mandate to cut that overgrown agency down to size again.

That was the outward purpose. It had been too big. It could indeed stand trimming. But while they were at it, they also wanted to make room at the top, and Congress, despite legislation to the contrary, passed new legislation giving the head of the agency the extraordinary power to let people go without reason — that is, not for cause but to reduce the force — and to cut out two out of three jobs on the level of people who earned more than $10,000. That means cut two posts out of three and that, of course, became a massacre in the Paris headquarters.

Now in a way I was lucky because Samuels, my boss, had foreseen this. He knew this was coming and he voluntarily decimated his division long before — that is, weeks before — this became an official mandate. By “decimate” I mean he cut out ninety percent of his staff and he went about this in a very clever way. He asked every member of his staff to write a recommendation saying that the basic premise was that the division will be cut to ten percent of its present strength and every person should recommend whose job should be cut out. Well, perhaps not surprisingly, most people recommended their own jobs for cutting. At least I did. I know many others who did. And so, we found ourselves without a job but, having done this before it had become an official assassination (that’s the name it was given,) we did not fall under an additional provision that had been made, namely, that those people who would be laid off will not be picked up by any other cabinet rank agency. They needed room at the top for their own Republican appointments. And one more thing: anybody appointed to a job on that level had, first, to pass the Republican Party Committee for recommendation. We found that outrageous. I later learned that the Democrats did exactly the same thing when they were in power. Well, that’s the system.

At any rate, we didn’t (we, the ones who had left earlier, didn’t) fall under this. I had asked for a year. That was the maximum: a year’s absence without leave. No, I beg your pardon. For leave without pay. And they kept my return ticket to the States, and the right to ship to my furniture back. They kept that open for a year. We decided, between Mommy and myself, that it was pretty senseless to return to Washington and compete with about 28,000 people who were laid off in this switchover of the two parties, cette alternance, and that was no time to go pounding the pavement in Washington. We would not stay in Paris, its being too expensive. Mommy took herself on the train to Nice and found an apartment, a very agreeable apartment in a nice villa, a huge villa which had been broken up into individual apartments, with a huge, old, overgrown park. This is where Madame Chur and her daughter lived, whom we befriended and still see. And we were going to live in Nice while I would — still entitled to PX, and cheap gasoline, and what have you — I would make a trip once a month to Paris and once a month to Germany and see whether I can find another government job.

Well, we proceeded to Nice, with you of course. We had, with many tears, said goodbye to Lenchen, had given her a nice present and she understood, and she went back to her home village. And we proceeded to Nice where we had a very enjoyable time. That is, we had about, something like two thousand dollars, (perhaps it was a bit less) and we knew that we can keep this up, oh, for about, you know, with accumulated leave and things, we could keep that up for at least three months, perhaps stretch it to four or more. And then we made another interesting discovery. Well, normally I’m a worry wort, and there I was without a job. I had no idea where the next paycheck was going to come from, no savings – we always lived it up – and yet I wasn’t worried. I enjoyed going to the beach with you and Mommy. We drove over to Juan-les-Pins, sometimes to Cannes, but more often to Juan-les-Pins. And this was in May, I believe. May and June were delightful. There were no crowds and it was delightful there, and we lazed around.

Then one thing happened which I remember very vividly. You were, at that time – what, four years old? You had gone to the UNESCO kindergarten in Paris, which was a multinational membership (that is, the people who had their children there were from many nationalities,) but the language of the school was French and English. And we spoke with you English at home, and Lenchen spoke German to you. You spoke both languages back at the level of a four-year-old, and that was that. You enjoyed the school very much. You enjoyed going there, and I brought you there while in Paris every morning. I don’t remember if I picked you up. I guess it must have been Mommy who picked you up because I was in the office. And then down in Nice, our bedroom gave out to a courtyard, and in that courtyard, there were other children and you played with them. And it was hot; I took a siesta, and I was dozing in the bed. I heard children’s voices. And then I clearly recognized your voice, but it couldn’t be, because you were chattering away in French. We never had heard you say one single word in French. And there you were, chattering away as if it were your mother tongue. Well, I got so excited about it that I opened the door and, by God, yes, it was you, and yes, you did speak French fluently. From then on, with all the children around you speaking French, you frequently spoke French to us, and we answered in English and you continued in French. That became particularly so when you eventually started going to school.

We had gone on home leave in ’51 and that trip is also unforgettable because — you know Dr. Spock who was the bible by which you were educated, for better or for worse (I say this because Dr. Spock has changed many of his ideas himself.) But at any rate he said that, if you can help it, you shouldn’t trouble with a child between the ages of two and three. And you were just three and, my God, was he right. You wanted attention. You refused to go to sleep. We stayed in, near the Nelsons, or at the Nelsons’ house. Yes, at the Nelson house, and it was impossible to go to sleep because you were crying all night long unless either Mommy or I carried you in the arms and walked up and down. We got desperate. We went to a pediatrician who told us that is not surprising. Do we, and he asked us how we left you in Europe. We told him that there was somebody taking care of you, and he said, well, that is very good for a child — and Mommy always had spent much time with you, in addition to Lenchen and Irmy — and the doctor said that when a child has its mother it doesn’t always have, it wants her not for 24 hours but for 25 hours. And you were awfully demanding on our time and what we should do is get somebody to stay with you while we go out. You would cry for a few minutes and that would, then, be that. And we found an elderly lady who was, perhaps, a little bit on the retarded side – I don’t know – but she had a particularly sweet way with children and with birds. A very sweet old lady, and she had a way with you. You took to her, and she found a method of getting you to sleep. She was going to show you how and she was lying down on the floor to, and faked sleeping, and you would lie in your bed, and you watched her like a hawk and if she opened her eyes, you immediately screamed at her, “You are not sleeping.” So, anyway, you were a terror.

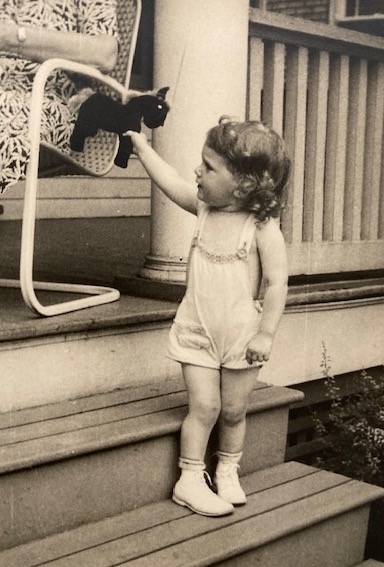

But, of course, you were also the darling of everybody who came to see you. You were particularly pretty, like a little angel with golden hair. You had a delightful German accent in English which, at least, delighted the whole family, and you said, “Don’t do dat!” Apparently, you had a very good time. Your English improved markedly, even at the age of three, during the short stay in the States. And Lucie came with her Monica, who had either her arm or her leg in a cast, and she was very envious of you because you got all the attention, and she didn’t.

Well, back to Nice. I said already that life was very agreeable. By that I mean it was considerably cheaper than Paris. We spent very little money. The climate was good, and it was conducive to, not only to doing nothing, but to do nothing and not worry about it. I started to understand why the Mediterranean French have a reputation for not working too hard. It’s extremely conducive to loafing.

But I did my first trip to Paris and there I ran into a former colleague of mine from the same division — he, also, in the same position as I: we’d both been riffed. We took news from each other, and he told me that he was, just then when I met him, on the way to Orléans where he was seeing somebody in the Personnel Division. They are looking for a contracting officer in the army. It was the Headquarters of the, USAREUR Headquarters of the Seine Area Command, and to my great surprise it was the same designation as the office for which I had worked when I was a soldier in Paris, and I sort of, offhand, said this to him and he said, “Well, why don’t you come with me and see the people there?” So, I did, and I was interviewed by the executive officer of the purchasing division, and he was a West Pointer who was terribly impressed by the fact that I came from the State Department. It meant a hell of a lot to him. And when he found that I worked in the general purchasing office of Seine Area Command, Headquarters USAREUR, he said I was made for the job. They had been just looking for that sort of thing. He would recommend me very highly and would I come back the next day? Anyway, within 48 hours they as much as hired me.

But, of course, as you know, in government nobody has the power to hire you. There are personnel offices to be gone through, forms to be filled out. I returned to Nice and filled out my necessary forms (or perhaps I had done this in Paris,) and then there began a long struggle. I was, on the one hand, told that I had been selected for the job as Deputy Chief of that division by the division chief. They wanted me. But there was something that had to be straightened out with the job description. They could not give me a grade anywhere near what I had when I was with the Marshall Plan. I would have to accept a GS-12, while what I had was between a 14 and a 15. But they would do something about it, and upgrade it, very quickly, and promised me all this. I went, very elated, back to Nice, and at the same time, while waiting for the paperwork to be done, and — what I didn’t know at that time and only learned later — there was a big fight between the general purchasing division and the legal office (the Office of the Counsel, Judge Advocate,) because the job description was written around my experience and called for legal training. And the Judge Advocate said, if you hire someone with legal training, he must be assigned to the Judge Advocate division. They had to rewrite the job description to say that they wanted legal knowledge, but it doesn’t have to be. Anyway, it took some time to do this. In the meantime, I was assured, I had been assured that I had a job and would get my assignment any moment now and, very elated, went back to Nice. We immediately asked Lenchen to come and we were now awaiting further developments.

At that time, the PTT was on strike. At first a postal strike and then it became a general strike. Anyway, there was no way of communicating, by telephone or mail, with Orléans or Paris. And somehow, I got (and I forgot how that happened, I did get, through Joe Slater who later also was fired by Stassen, but I think it was through Slater,) that I got the message that there was an inquiry from Korea. At that time, the military government in Korea also had changed into some sort of a High Commission and Dr. Karl Bode, who was a friend of mine from Petersberg days, had asked whether I was interested in coming to Korea. Well, that was a big job, and I was very flattered and keen on it and there was no way of cabling my answer. So, we took the car and went into Italy, and I sent off a cable which at that time cost something like twenty-eight or thirty dollars, and which, incidentally, the Italian postal employee apparently pocketed because the cable never got there, which was just as well because the assignment to Korea would not have been a very desirable thing. Bode ended up there; he was the head of the economic mission. He ended up with a nervous breakdown, and that may very well have been my fate too.

So anyway, we had then a long wait. It took until, I believe, May, June, we were, it took more than two months, but two months where I felt that I had a job, even though I didn’t have a paycheck yet. Lenchen had arrived. We took off for a trip. I took Mommy, for the first time, to Venice, and we were on top of the world. Eventually, my papers came through. You and Mommy stayed, we stayed — I believe a total, we occupied the apartment for a total of about four months. I believe one month after I had assumed my job in Orléans, Mommy came to Paris, and she found the apartment on Boulevard St. Michel because that was close to the Gare d’Austerlitz where I took a train at seven o’clock in the morning every day and, incidentally, I did this for three years and I never missed the train. I once missed it coming back from Orléans to Paris, but not going.

And thus began my work for the army in procurement. In the legal division there was Don Ruby and, since the purchasing division has a lot to do with the Judge Advocate, with the legal division, I became very fast friends with all the people there in the legal division.

They were delighted to have somebody who somewhat spoke their language. There were some other adjustments I had to make. This was the first time I was working for the military as a civilian and I had made up my mind about one thing. If the army can take the position that any officer must be able to perform any job assigned to him merely because he is an officer, well, what an officer can do, I can do. I was not going to be overawed by rank or anything, and when I was a couple of days being there, taken to the General’s mess and introduced to the General, I just spoke to him as I spoke to anybody else – and that became a pattern – because I discovered that when you’re talking to high brass, military, diplomatic, or industrial, the way you talk to them is the way they talk back to you. If you talk to them as an equal, they take you as an equal. And I was never in any trouble on that account.

I was very politely treated, particularly thanks to the executive officer who was so impressed with my background and, very soon, became very close to then-Colonel Roberts (who later became Major General Roberts,) who was negotiating an agreement with the French, and I had quite a lot to do with that agreement, in communications on agreement. It was sort of a headquarters agreement of relations between the host country and the army. And that got me introduced to the French liaison mission, which was an organism created to do liaison with the Allied Forces stationed in France and established a very good rapport with them. You can imagine, speaking French, there weren’t too many who did on the American side, and it was a very pleasant time. I refused to move to Orléans, which is not a place I would want to live at, to live in, and didn’t mind the commuting. As a matter of fact, we were, all forty, doing this every day, and we were all trained to make that train by the skin of our teeth in the morning and immediately go to sleep until we arrived in Orléans, where a bus took us to the Caserne Couligny where our headquarters were, and the reverse took place in the evening. It was a long day. I left the house in time to make a seven o’clock train, and came back about seven o’clock again, before I walked into our apartment, a very pleasant apartment except that it was walk-up, and Boulevard St. Michel got to be louder and louder. But aside from that, it was very pleasant, and I enjoyed my work. I did something interesting and constructive, much more than on my previous job, and very shortly — oh, only after about six months or so — my job was upgraded into a GS-13, which was already closer to what I had had before.

I enjoyed what I was doing. The most amusing thing was that I had been hired practically on the basis of the fact that I had already worked in that very same office during the war and — look at all the past experience. Now what I had to do then, in Orléans, had absolutely nothing to do with what I did in that office during the war. There we had lend-lease and reverse lend-lease, and nothing of the kind existed now. But there was enough work to do, contracts to write, negotiations to be held, and particularly negotiating with the French liaison mission, the form of contracting that we had to undertake.