Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 10A, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

……………..

The Park Hotel was billet for the field grade officers or, rather, general officers. That means people from lieutenant colonel upward in the British – my civilian rank as a counselor of embassy was about equivalent to that of a British brigadier. (Lest I forget, let me mention that ever since my job as a head of the political division in military government in Hessen, which I held briefly, and then the job in Düsseldorf, were State Department assignments. I switched over to the State Department at that time.) The British are terribly rank conscious, and their army is regarded — was then so regarded — as an elite affair and particularly high-ranking officers hold a respected social position in England.

Well anyway I was assigned to a very decent room (you know, old-fashioned with lots of heavy velvet curtains and the like) and I remember I woke up – oh, yes, I was considered a bachelor because my family wasn’t with me, so I’m a bachelor – and I woke up in the morning with the unpleasant feeling that there was somebody in my room. Yes indeed, there was. There was a man who visibly opened the curtains of the window, put something on my night table and, sleepily, I asked him, “Who are you?” He said, “I’m your batman.” “You are my what?” “Your batman.” Well, apparently, I was entitled to have a batman, the English term of what we call an orderly, and when I asked him what his duties were, he said, well, to take care of my clothes, keep it clean and brushed and pressed, shoes cleaned, polished, and to bring me my morning cup of tea which apparently a good Englishman is drinking in bed before getting up. Well, I told him that I don’t wish to be awakened and I certainly don’t want to have that awful brew which the British insist on calling tea, and when I want him, I’ll call him.

Eventually I went down to breakfast and there got my first experience of British gentlemen in a club atmosphere. At every table there were two, three, one person, and each one of them reading a newspaper, either waiting for his breakfast or while eating it. I asked permission to join (there was no free table) some two gentlemen at a table. They wordlessly nodded, and I said, of course, “Good morning,” which earned me a dirty look away from their newspaper to which they immediately returned without a reply. Ah, alright, first lesson learned.

The whole place smelled of kippers, which isn’t too bad. I like kippers. In fact, I like kippers for breakfast. The smell is the worst part of it. But it was a good thing because the rest of the time the hotel dining room smelled of brussels sprouts which was served throughout my stay there for the two other meals. I haven’t been able to enjoy brussels sprouts ever since.

I proceeded to the office, met my colleagues. I had already met Mr. Parkman, who had interviewed me at an earlier occasion, and we were a small office. The U.S. delegation consisted only of four people, that was: Parkman, his deputy Don Wilson,

myself as a political advisor, and a legal advisor by the name of Phil [Abbots?]. And three secretaries. Well, one of the things that became abundantly clear after a very short time was that this organization which we all had regarded as the one thing that will last into the future was doomed from the beginning. It dealt with an issue, important at the moment; but its creation coincided or, rather, was almost immediately overtaken, by the establishment of the Coal and Steel Community, or what later became the Coal and Steel Community — the Schuman Plan, in Luxembourg, the grandchild of Monnet. And that was pretty clear to us. However, until they could get going, we had to fill the gap. It did something to our morale because, it’s devastating for your morale to work for an organization that you know is about to liquidate, and particularly when, as in our case, you first had to establish the organization for the very short transitory period until it would have to be liquidated. However, the people I had the pleasure to work with were interesting and we were not overworking ourselves. We had plenty of time for talking.

Let me give you some of the people we met there, or I met there, and eventually we became friends. One of them was Murray Marker, who was not in the U.S. delegation but was on the international staff as a legal advisor, who introduced himself and we very quickly, within minutes, hit it off with each other.

Don Wilson, the deputy of Parkman, became a good friend. An interesting self-made man – I don’t remember whether you ever met him – he used to work in the Bureau of Mines in the States and was a coal expert. Then, further on the international staff, there were Dick Dobson and Eddie Luff, both on the International Secretariat under the Secretary General who had the amazing name of Mr. Kaeckenbeeck, a Dutchman [ed: Georges Kaeckenbeeck, Belgian,] and they were young and, at the time, rather junior employees in the International Secretariat who took care of, partially of translation and partially, partly, of conference services. We became friendly with the Luffs because we invited them, we didn’t make any pretense of, or made anything of, the very considerable difference in grade. We just treated them as friends, and they appreciated that very much.

The meetings we had were at a long conference table and I found myself in rather illustrious company. The German representative was the Vice-Chancellor, who was also Marshall Plan Minister, and he was Germany’s delegate to the Ruhr Authority. He was Vice-Chancellor Blücher, a descendant of the German General who contributed so much to Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. The French delegate was Alain Poher, who at that time was prominent in the party which had furnished the French premier, Schuman, and which was very close to the German Christian Democratic-type party. And Poher, who was the mayor of some town in Germany [ed: Ablon-sur-Seine, in France], well, as you probably know, he has made considerable career since. He has been for the last ten years or more President of the French Senate and, for a short period after the death of Pompidou, he was President of France. Parkman, Poher, the British representative, all had ambassadorial rank and the Benelux countries sent people with ministerial rank. At the table, each one of the delegates was flanked by his deputy and political advisor so that put me at the same table, and I sat next to the German political advisor, which sometimes served a dual purpose because I was able to intercept some of the conversation between him and his minister (not that there were terribly secret things being said.)

But perhaps I better interject here something which you might not know. One of the consequences of the German surrender was the decision by the Allies, very much pushed by the Russians, to dismantle the German industrial plant – and I mean all the important German industrial plants – and transfer them to the victors, particularly to Russia. In reality, this worked out not at all as expected. Some of the factories, or the machinery, which was brought to Russia, was then left standing in the open and rusted away because nobody knew what to do with it. And the Germans found themselves with bare halls, factory halls – or rather, what was left of them — and were able to rebuild later when the Marshall Plan came, with the aid or the financing of the Marshall Plan, brand-new, ultra-modern plants. And perhaps that was the seed of the German dominance in the present day as an industrial giant in the European West.

The sole purpose of the Ruhr Authority in Düsseldorf was to see to it that the German coal gets produced and then divide the total production among the Allies and Germany. It was a pushing and pulling and, obviously, everybody was terribly hungry for coal. (Incidentally, there was a similar body in Hessen doing the same thing for steel production, belonging as it were to the same International Ruhr Authority, but they were two distinct bodies and ours was concerned with coal.). The High Commission which had replaced the military government had, by then, established itself at Godesberg [ed: Bad Godesberg, a suburb of Bonn] with its administrative seat on the Petersberg and particularly the U.S. pushed for a program of increased productivity. We were going to put American know-how to the – American, what do they call it? P.R. know-how – to the task of pushing coal production and thereby steel production.

The U.S. head of the Marshall Plan which had come into being in Godesberg was one of the more brilliant assignments made by the U.S. government. He was Michael Harris, was a union man, who was a genius. He had become Secretary of a large U.S. union, I forget which, before he was of voting age — and was a trained economist, splendid speaker, brilliant strategist. And the idea of sending a union man into this — by this capitalist country, America — to Germany, was a stroke of genius. I met Michael Harris in many meetings because I had dealings with the U.S. delegation on the Petersberg because of the close relationship between coal production and our task. The Germans, incidentally, at that time also had a genius as the head of the German unions. Dr. Heinrich [ed: Hans] Böckler was a self-made man (his doctor title was given him as an honorary title) who had the seemingly simple idea (but it proved to be a genial ideal) to keep one thing that the Nazis had done and that is a unified, a single union.

And the Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, under now Social Democratic majority, proved to become under the very wise leadership of Böckler one of the best syndicates that I’ve ever seen in operation. He was able to persuade the workers that, before anything else, you have to rebuild German industrial capacity and for that, you need capital, and you have to keep the demands for wages and fringe benefits to a minimum. You have to all pull in the same direction. There was no talk about the class war and there was a reasonable understanding between management and the work force. All that, thanks to the enlightened leadership of Böckler.

My relationship with Mike Harris was an interesting one. We met at a meeting where we were talking productivity and I don’t know whether you have ever experienced this – it was something like instant friendship. We became friends within minutes, and I mean friends. An incredible affinity. For years, I used Mike Harris as my outstanding example when people told me, well, Jews tend to only be friends with other Jews, very few Jews have truly non-Jewish friends and I always retorted angrily that this wasn’t so. I had quite a number of non-Jewish friends and gave as an outstanding example Mike Harris. And it was only about six years later that I discovered that he was Jewish.

My frequent visits to the Petersberg brought about a budding friendship with Joe Slater who was the Secretary General of the U.S. contingent in Petersberg. He was the Secretary General of Mr. McCloy and there too, we became very good friends and the families saw each other frequently. Joe Slater had on his staff a number of people whom we still see, such as Hugh Wolff who was in the Secretariat, who worked for Joe. Later on, when Herman Elegant lost his job (when they reduced – or rather, phased out — military government courts in the U.S. zone,) Herman Elegant, whom I recommended to Joe, also joined his staff. Jerry Knoll was not working on the Petersberg, but in the economic division. He was an economist and worked for Karl Bode, a German-born professor of economics who played a role later on. Now, these were all highly interesting contacts as you can see from the names. They resulted in lasting friendships.

While there was reason to feel slight frustration with the uncertain future in the Ruhr Authority, it was, for me, a very interesting time. Joe Slater had the very reasonable attitude that in my position as a political advisor and with a “top secret” clearance from the U.S. government, I had a need to know what was going on, and thanks to him I knew a lot about what was going on in Germany on the top level. Joe always participated in the meetings of the High Commissioners with Adenauer, who was Chancellor at the time, and I learned a great deal about what was going on.

As to our personal life, Mommy and you had come up after I had been assigned an apartment on Cecilienallee. It was similar to the one we have here in Paris, a double apartment, not terribly satisfactory, but big enough (it had enough rooms.) But we were entitled to a house, wanted one, and it took a while before we got it. We eventually got the house that the Markers had, which was in the Lilienstrasse. It was a lovely house and we got that when the Markers left, and that is considerably later. Lenchen was with us; we brought her from Wiesbaden. And Irmy took care of you.

Our social life was a highly international one. There was not too much contact with the German population. You see, Düsseldorf was, and still is, a rather odd town. It is a playground and the shopping center for all the rich people of the Ruhr region, and there still were some rich people. There wasn’t too much to be had in the stores, but the city had not changed that character. And we had so much contact with the other diplomatic personnel that there was not too much occasion to meet Germans other than business. Eventually, I got more contact because Mike Harris had the idea of establishing a speaker’s bureau to teach people to speak to crowds to push productivity. You know, this was not limited to coal. It was generally a push for productivity with the infusion of capital coming from the Marshall Plan to rebuild Germany. This also coincided with a complete switch in our overall policy, which was originally one of demilitarization, to remilitarize Germany but on our side. It was the beginning of what later became NATO, of a Western military alliance, a sudden awakening that the honeymoon with the Russians was over.

As a matter of fact, this complete switch in policy caused a lot of soul searching for all of us. I remember while still in Wiesbaden, I wrote a very disturbed letter to what was, in a way, my boss in the political division, in the State Department in the States. I confessed to my great difficulty in adjusting to the idea of switching from demilitarization to almost the opposite. Not almost – to the opposite. No, I told him that when I was in the States – I didn’t write him a letter – it was in a conversation. His name was Schwartz and when I told him about my great admiration for Acheson and the fact that I had heretofore joyfully carried out all policies under the aegis of Acheson’s policies which emanated from the U.S. government but emanated from that Secretary of State, and he made a very wise observation which helped me — which I believe is worth recording. He said, “You just told me that you admire Acheson and that you agreed with everything that he has so far done, and you followed that easily. Now, would it not be intellectually fair to admit the possibility that when for once, he is dictating a policy with which you do not agree, that you give him the benefit of the doubt, that he might be right, and you might be wrong?” I agreed with that analysis and found it possible to readjust my thinking.

But, back to Mike Harris’ idea of a speaker’s bureau. He asked me to take part in this and hold courses, or seminars as it were, in the field of coal production, which I did, and that got me in touch with numerous people. And also, at one time, it led to the fact that I was sent to a meeting in the Industry Club. The club of German industrialists was a highly capitalist, originally rightist, nationalistic German organization, which somehow had revived after the war and, of course, we didn’t know whether the people, in their heart, had changed. It was not my crowd. And Peter von Zahn was holding a speech there about the International Ruhr Authority and I was sent there as an observer from the International Ruhr Authority. Well, let me explain the position of Peter von Zahn. He was a commentator on German radio and by far the most popular one.

He was the Cronkite of German radio. He had the incredible gift of looking at things positively, and a further gift to couch criticism into language and, when you saw him, a smile which was neither sarcastic nor cynical but just showed sincerity, and you could never get mad at him. Well, during his speech — after his speech, rather — he invited questions and, obviously, I asked some, or made some observations — or rather, argued against some of the things that he had charged the International Ruhr Authority with. It became sort of a friendly duel, as it were. Very polite and very substantive. Nothing personal. And after the meeting – I had to identify myself; I was identified as coming from the Ruhr Authority – and, after this meeting, Peter and I repaired to a café and talked some two hours more, and we became fast friends and saw a lot of each other later. Subsequently, rather.

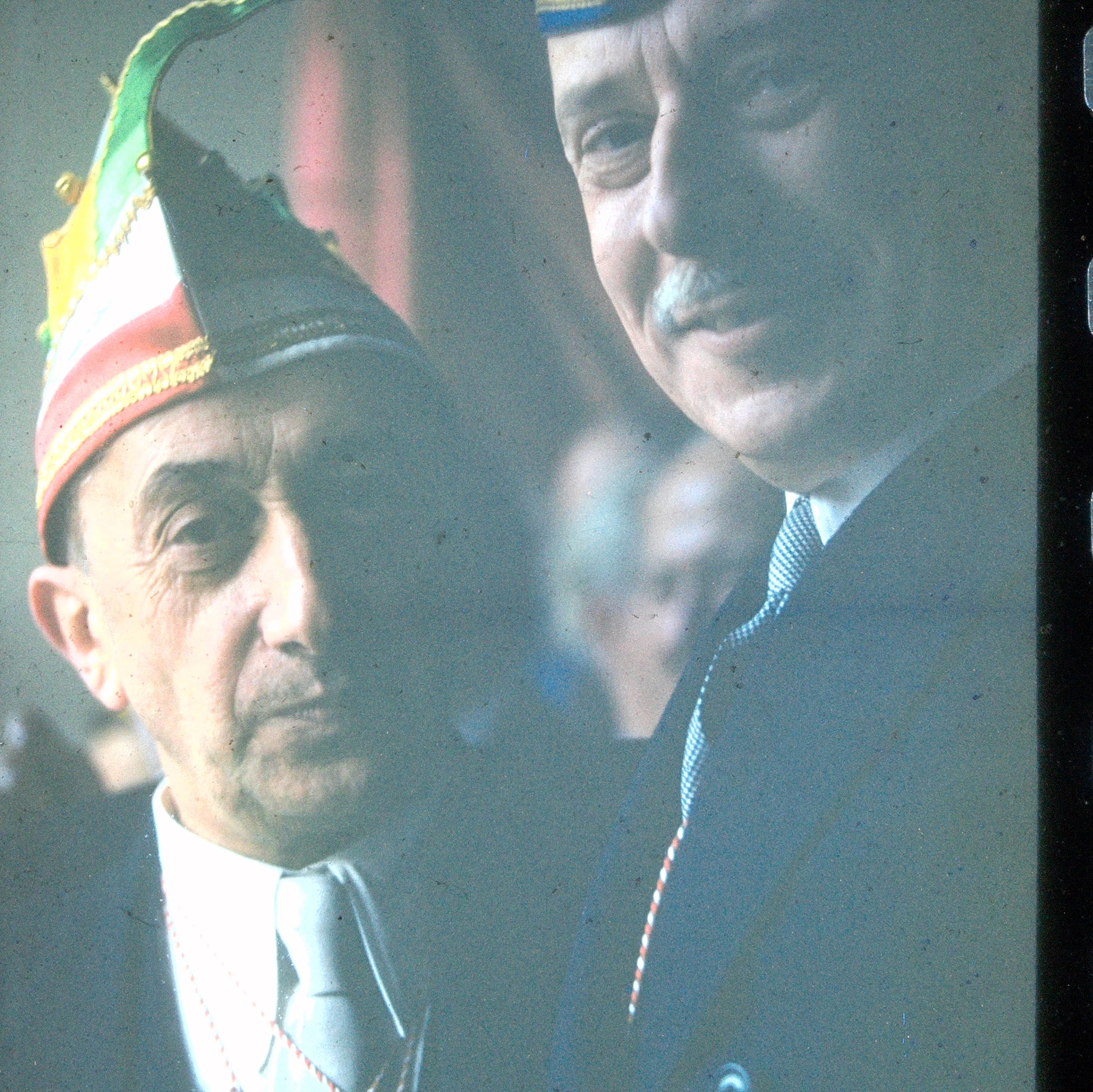

Photo: V. Gruder

And one day he said, “I want to introduce you to people who you will enjoy very much.” And he took us to the Kommödchen and this is how we met the Lorenzes. This is how our friendship began. Obviously, we were very, very impressed with their program and we liked them as people. Then followed something which I look back on with great pleasure.

The Lorenzes were both considerably, were both much younger than we are, and were, during the war – well, when the war began, they were students. They confessed to a terrible ignorance about democracy, about the democratic process, democratic institutions, and they were extremely eager to learn. Well, so far, so good. What I hadn’t bargained for was that every word I said was taken as if I were Moses, directly coming from the mountain. I realized that only once when, two years later, Kay quoted back to me something that I had said two years earlier. I realized suddenly that there was a responsibility that I had sort of automatically assumed, of speaking when teaching, speaking about and teaching, democracy. And I also realized that the Lorenzes spoke to a large public. It was through them that ideas were brought to the Germans. I felt that responsibility and was careful what I said.

The most difficult part of it was that the Lorenzes were instinctively, like all the other Germans, like them, most pleased with the anti-militaristic policy of the U.S. government. They didn’t want to have any war, and they didn’t have any military, and the slogan at the time was, “Ohne mich” [“without me”]. Well, I had considerable soul-searching to do, as I told you. That’s because by now, it was no longer a question of carrying out instructions. I was faced with a task of convincing the Lorenzes to change their position from one of blind pacifism, as it were — or blind anti-militarism — to one where one did recognize that the relationship with Russia had indeed changed. Oh, I don’t know whether it ever was any different, but that our position, the West’s position vis-à-vis Russia, had changed and a reorientation of your thinking was necessary. And eventually, I believe, I was able to succeed in making them see that.

The Lorenzes were struggling. The Kommödchen brought income, but food could still only be gotten on the black market. We are still in 1949, ’50 — no, rather ’50. And, I don’t know, it was I think in 1950 when we rented a villa in Le Coq together with the Luffs for the summer, where Mommy and Yolanda stayed with the children and Irmy and the two maids, and Eddie and I came every weekend.

And I had the idea of inviting the Lorenzes. Lore was at the time pregnant with Katika, I believe (I don’t know, with one of her children, perhaps it was the last one — I forget, I don’t remember exactly how old they are,) and I invited them to Le Coq, put them up in a hotel, and, of course, one couldn’t take any money out. Germans couldn’t travel outside Germany, so it had to be done strictly through myself. I took them in the car. Lore later confessed that, not being used to American cars and to the brakes of American cars, that during that drive she was so scared, that every time when I came close to the back of another car, that she was afraid she was going to lose the baby. Anyway, the Lorenzes have never forgotten this early invitation and sort of credit us with – it played a considerable role in their own memoirs.

We had an active social and cultural life. The orchestra of Düsseldorf was led by Heinrich Hollreiser, whom we met and whom we invited to the house. We didn’t become great friends, but we saw each other every so often. I think I told you in another context that we met each other later during a performance in Vienna. And there were other rather memorable social events like an invitation to the Mayor of Cologne where we viewed from the windows of his office the famous carnival of Cologne. And I have some rather interesting photographs of that with the British High Commissioner wearing a fool’s hat.

It was an interesting and full life we had at the time and, by 1951, it became clear that the Schuman Plan was getting into gear, and that the Ruhr Authority would be liquidated soon. Mr. Parkman left and became the U.S. head of the city of Berlin which continued to be occupied by the four powers, and he was the — he became the U.S. head. Later on, he became the U.S. Marshall Plan representative in Paris.

I’d like to say something about Parkman. He was not only an extremely intelligent man. He was a perfect gentleman, a marvelous human being.

I mentioned that he came from an originally rich, and patrician, Brahmin family in Boston. At an early age he decided to go into politics, and if you want to go into politics in Boston, you’d better know something about the people you want to vote for you. So, in order to do that he became a stevedore which he stayed for something like eight months or a year, and this, at the time — and this wasn’t the usual thing to do for a Boston Brahmin. A wonderful person, married to an equally wonderful wife.

We had great, great evenings with them. They lived in a house, also on the Rhine but on the opposite side from Cecilienallee. We could practically see each other’s windows and one day we invited them. I devised an invitation which was a satire on the kind of invitations we got from the military governor of the British zone, a Major General who was a pompous ass, and I wrote it in the same vein as he did, explaining how to get there, just getting over the bridge to a house that you could see. And I said, for “dress,” “any old dress.” Well, Parkman arrived in tails and his wife in an evening dress, and he explained that that was “the oldest dress” he had. He also came with an enormous bush of flowers because he never could get over the idea that the Germans, when they came by invitation, handed the host a bush of flowers, and he never knew what to do with it — put it between your legs while you shake hands? He couldn’t get used to that habit, so he tried it out on us to get practice, he said.

He spoke the kind of English you would expect a Harvard graduate to speak. An educated man, but he could get mad and when he did get mad, he remembered his vocabulary from his stevedore days.