Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 9B, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

……………………

I knew a lot about these camps – rather, I knew about their existence – because the people in these camps came under the jurisdiction of military government courts. I have told you before that the military government courts took jurisdiction and held trials in all those cases in which the victim or the offender were Allied soldiers or Allied civilians in the status of displaced persons, and in status 5, persecutees under the de-Nazification law. That was the extent of their jurisdiction, and I did mention that German law was applicable and American rules of procedure applied. Incidentally that also included traffic accidents or, rather, traffic offenses beyond speed limits and things like this. Accidents with some great consequences.

Our first visit to one of those camps, I mean Mommy’s and mine, came about in the following manner. Somebody in the States had sent us a number of parcels containing clothing and underclothing and things like that, with the instruction of bringing this to their relatives. Well, we discovered the relatives living outside the camp, on the economy, and not in need of these clothes, and they sent us to the camp and said, “This is where such things were needed. You should go there.” So, we proceeded to a place, again near Darmstadt. We found a strange mixture. There were people quite well dressed, exceedingly well dressed. Those were the black marketeers. They did a thriving business. Within the camp, with the Germans, black market was all pervasive. I have explained before that black market was an unavoidable consequence of the situation and some people benefited as traders from it, not particularly perturbed by any moral scruples, because they had no particular reason to love the Germans and they did something like personal restitution – getting some of the things back, as it were, that they had lost (although what they had lost to A, they got back from B, but that’s a minor detail.) Also, I have mentioned that the people, survivors in horrible times, by definition, are thick skinned. They have the gift of survival and it’s survival of the fittest. Not necessarily mentally the fittest but the strongest. That is not a moral judgement. It’s again a fact of life so they were not the cream of society but there they were. And, right mixed with them, were people who had nothing to trade, or didn’t know how, and who were in need, and who lived on the rations.

I forgot what we did with the clothes, whether we left them there or not, but I also know that there was a raincoat, a small raincoat, and – a small-sized raincoat – and the relatives for whom they were intended gave us the address of Ilonka. We sought her out and found her living in a room on the economy. A tiny, birdlike creature, hardly weighing enough – you had the feeling you could lift her with one hand. And absolutely no such thing as black market. As a matter of fact, she was so shy and so frightened that it took all of Mommy’s warmth to persuade her to take that raincoat which fitted her. She insisted on paying for it and we sort of drew that out. Eventually we persuaded her to come to our house, fed her a meal. Again, the meal would have been enough for a sparrow – more, she couldn’t eat. And eventually she became like a tamed animal, she took to us, she saw that we meant well, and she sort of became a constant feature in our household.

We know relatively little about what had happened to her. We know that she was originally Hungarian. She was in a concentration camp, but it was a subject one couldn’t discuss with her. She wouldn’t discuss it and after a while you didn’t probe. You learned very quickly not to probe into the minds of people who had experiences which they wished to bury. Her relations to the Germans around her were interesting. She lived a good distance from us and could have reached us easily by taking a bus. She preferred to walk rather than being surrounded by Germans. Yet she was very polite and friendly with Lenchen; she was polite and friendly with everybody. But not sociable with Germans and she met Germans in our house. She met Marianne, who sort of also took her under her wing and eventually she accepted Marianne. But generally, she still was a frightened little bird.

It was only during our last visit, in New York – oh, yes, she eventually got a visum to the United States, and she married another ex-Hungarian, also a survivor of a concentration camp, Shandor, with whom she was very happy.

She was a beautician by training. In New York they had family which behaved admirably to them and staked them to an apartment, and eventually she got a beauty salon in which she did very good business. He worked for a company and, unfortunately, Shandor suddenly died about two and a half or three years ago. The last time we saw her in New York, which was in ’78, I asked her, how did she learn English? I didn’t remember whether she knew any when we met her in Germany. And to my great surprise she said she learned it from us. So, apparently she, simply by being around us, heard enough English to pick up enough to converse. She still has a very strong Hungarian accent, and her written English is full of mistakes. But I believe she nevertheless did admirably well and to her, the United States are paradise. The only cloud on the blue sky was the death of her beloved husband from which she has not yet recovered. [Ed: Victor and Jeannette and Ilonka stayed in close touch with each other and visited each other throughout the rest of their lives.]

West Germany was teeming with displaced persons because not only were there the relatively few survivors of concentration camps, there were the people who fled, as I said, from the Eastern part of Germany, afraid to be caught by the Russians. There were all these workers, Zwangsarbeiter, people who were forced labor, and had been imported by the Germans to work in the war factories, imported from all the conquered territories. And in addition to this, there were the Germans who were expelled from the Easternmost portion of Germany which was claimed and occupied by the Poles. And then there was a large movement of Germans out of that part of Germany that was occupied by the Russians because if — among the Allied military governments there were various degrees of harshness with which the German population was treated, the greatest fear they had was of the Russians. This fear was somewhat — not “somewhat.” This fear was justified because the Russian troops which had overrun, during the war – towards the end of the war – the Eastern portion of Germany, were indeed not very tender to the Germans. There was, for instance, in Austria, which the Austrians would like to call the liberation of Austria but which to the Russians was just another province of Germany, there was a hell of a lot of raping going on. Raping and looting. In Berlin we know at least two women personally who had been raped. And in Vienna the Russian war monument, on the Schwartzenburgplatz, was baptized by the Viennese as “The Monument to the Unknown Raper.”

Add to this a trickle and a stream of returning German war prisoners, made prisoners by the Western Allies and eventually let go, discharged. It took much longer to be discharged from Russia, from Russian-occupied territory, and there was a steady search by the families who looked for their relatives — who knew or who thought they knew were prisoners of war, or hoped they were prisoners of war, and might return. And every train that came and brought prisoners, there were thousands standing and people approaching them: “Do you know so-and-so? Where do you come from?” There were long lists of names posted at the railroad stations with requests addressed to the returning soldiers to give news of those whose names were listed.

I’m telling you all this because it may perhaps begin to convey the picture of the total chaos which obtained and yet, in the midst of this chaos, some order began to emerge. It was mostly due to the efforts of the democratically elected German governments on all levels which tried to reorganize a new life but a new life in a vast, destroyed country where you had to start from scratch. It’s an unbelievable undertaking and nothing short of a miracle that it worked at all, that it worked well, and amazingly quickly. For us it was fascinating, exhilarating to take part in this constructive effort. You had the feeling that you did something worthwhile, and we enjoyed this.

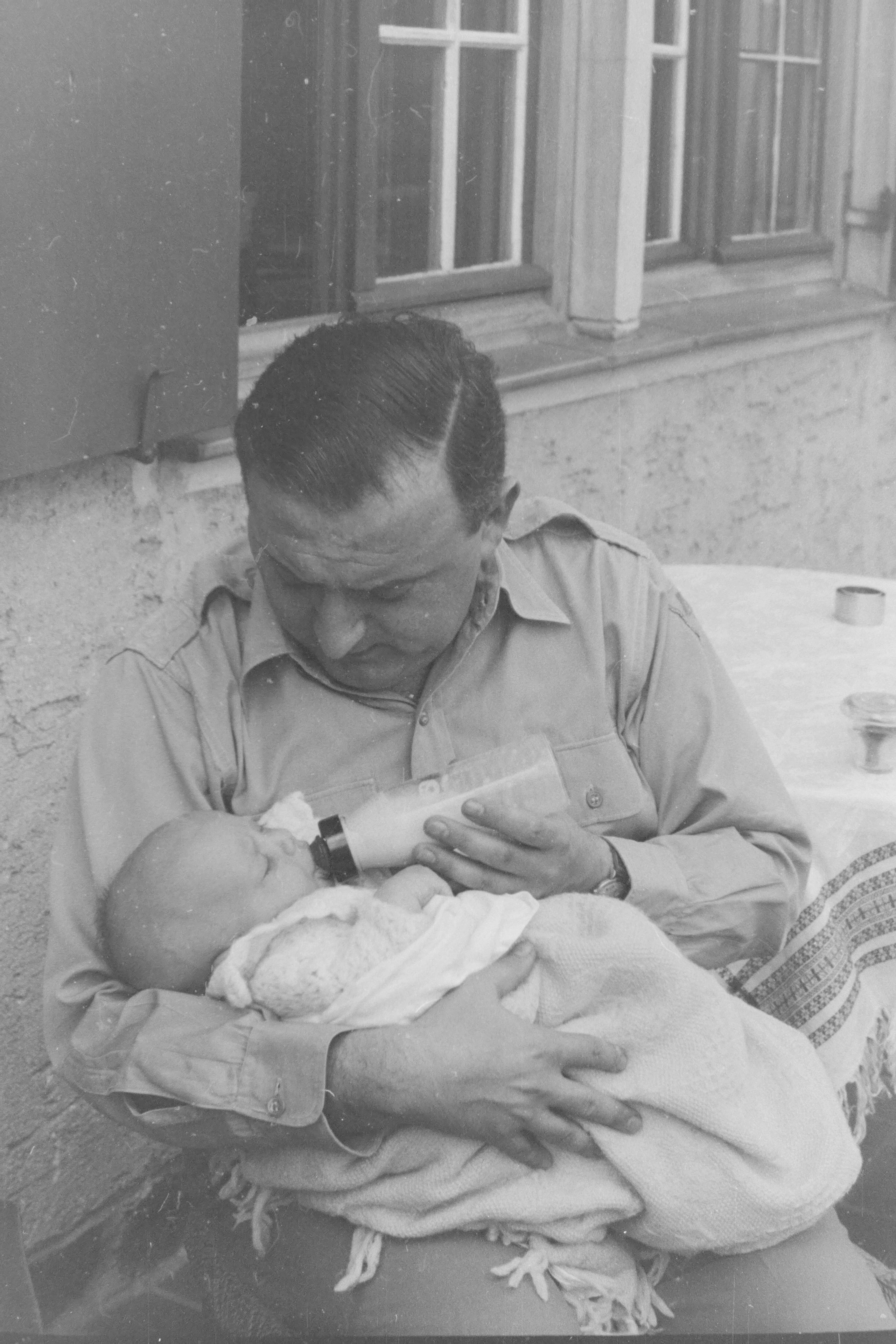

We also enjoyed now being newly baked parents.

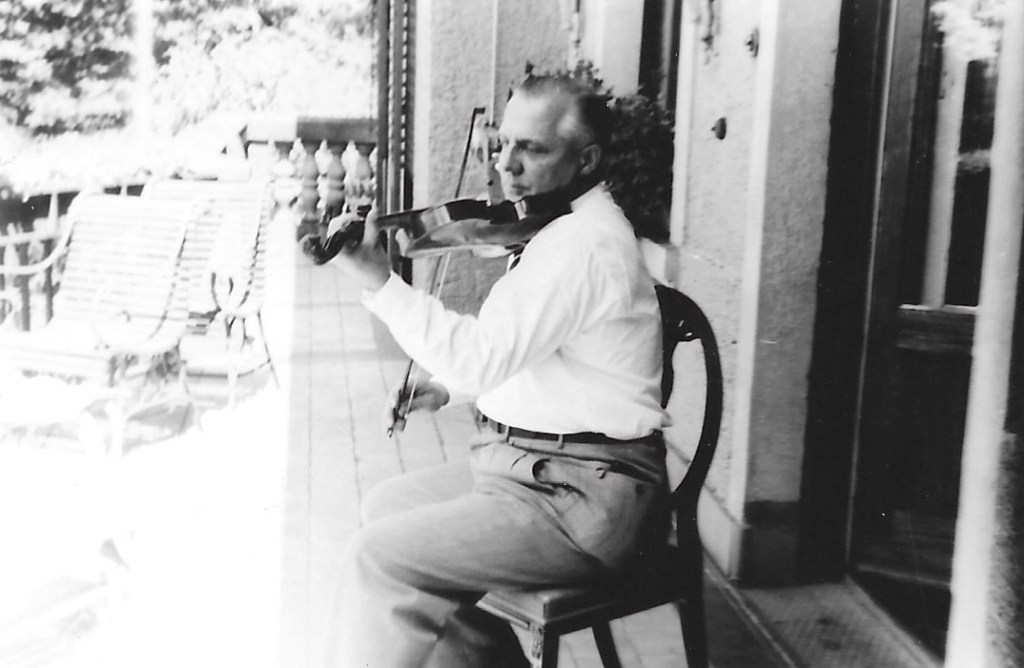

We had all the help one could need. We lived in a wonderful house. We had many friends who came to visit. And, well, to give you an idea, at one time we gave a party in Schwalbach in which we had twenty-eight people for a sit-down dinner. That gives you an idea of the size of the house.

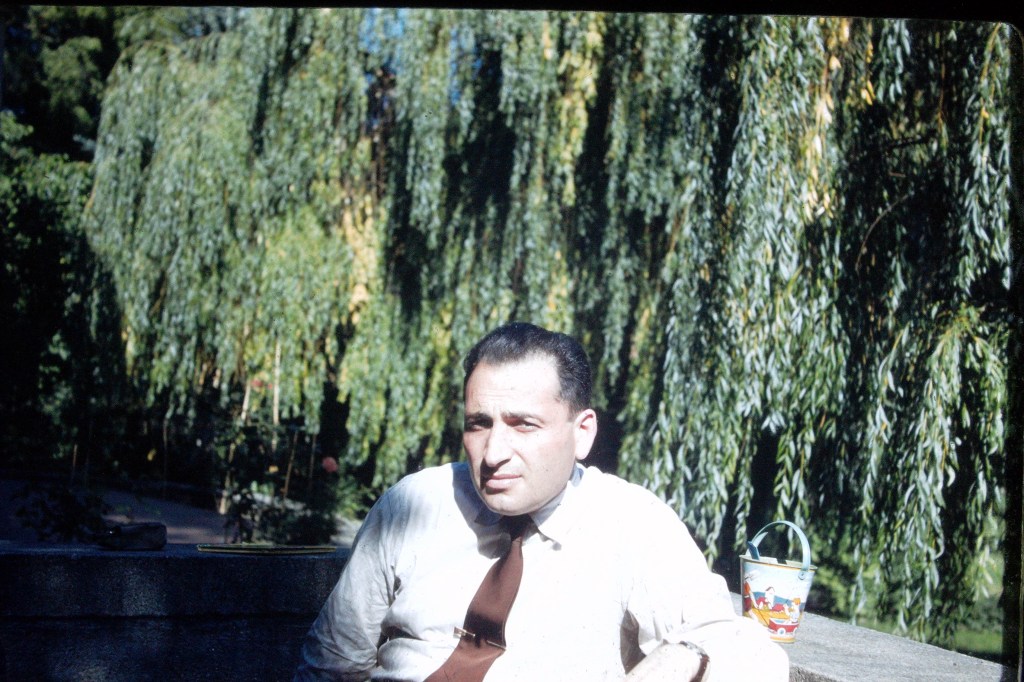

Perhaps I’ll tell you a bit about our friends, or rather the friends we made then, because quite a number of them are still our friends today. Well, there were the Elegants. I found Herman Elegant who had been a soldier in military government attachment.

He came with the army. He was a lawyer, became a civilian in Europe, and was assigned to the legal division in Wiesbaden where I met them. He was a military government court judge. Guggi, I already mentioned.

Then there was Frank Potter, the head of the legal division, who later married an opera singer from the Frankfurt Opera, Erika Schmidt.

They live in Bad Hamburg, and we still exchange letters with them.

There was Marc Robinson, who was his deputy, who later became a military government supreme court judge and, until his retirement, was on the appellate court for restitution in Germany, a court which passes as a last instance in restitution cases. He still lives in Germany today.

Then there was Ted Ellenbogen whom I already mentioned, for whom I worked, who returned fairly early to his job in HEW where he was legislative attorney until his retirement a few years ago.

With me in his office was Tony Crea. I don’t believe you have heard of him, another New York lawyer but, interestingly enough, I ran into him when I worked for DSA, and he was involved with myself much later during our stay assignment in Washington. We carried on the crusade against pharmaceutical companies for the Defense Department. It was George Moore, a neighbor of the Elegants now, who then was one of the military government officers.

And then there was somebody with whom we were friendly but, unfortunately, we have lost track of him. His name was Heinrich, and he was a fine arts officer. He later became head of a museum somewhere in California.

But Heinrich triggers the memory of some extraordinary events which we lived through in Wiesbaden. Let me tell you about it. As you probably know, the Germans had looted art from all the countries which they had overrun. There were several categories. Some of it was looted, as I told you before, by teams which looted more specifically for specific clients such as Hitler or Goering, and others which just looted. And it was brought to Germany and there, since Germany was later under air attack by the Allies, these art works were buried in salt mines. Next were the possessions of German museums and churches which were moved to safety by the Germans, also into these salt mines. Now the Allies set out to gather all this stuff, to find it – well, we had found it – but to catalogue it, find the origin and return it to the rightful owners, museums, all over Europe, private owners, and that was quite an undertaking because there was a hell of a lot of it. And they had also moved out of Berlin – the Germans had moved – the whole contents of the Kaiser Wilhelm, Kaiser Friedrich Museum (I forgot now what the proper name is: their largest museum,) and all this was in salt mines in Bavaria. Now Heinrich and another fine arts officer in Wiesbaden were the people made responsible by the U.S. Government for making Wiesbaden, a relatively little historic town, the central point for gathering all these things — that is, bringing it from the salt mines to a central point which was the museum in Wiesbaden. And that entailed a number of rather complicated, logistic problems, and even security problems. The security part of it is the funny souvenir.

They found the tombs or, rather, the sarcophagi of Frederick the Great, his wife, and Hindenberg in the salt mine of — somewhere in — Bavaria. There was great concern in Washington that both Frederick the Great (who is a historical figure in Germany, much revered) and Hindenberg, if one were to make a public transfer of their remains to a, whatever, place in Germany, that this may become the focal point of a new nationalist, and a revival of Nazism, and what have you. Anyway, there was concern that this must be done very quietly and highly secretively. But it was decided in Washington to rebury them in Marburg, in the church in Marburg. Why they picked Marburg is beyond me. Marburg was one of the, had a university which was known to be, one of the most reactionary — or rather, full with reactionary professors (because, quite in distinction to France where the teaching profession traditionally is somewhat left of center, in Germany, the higher up you went in the teaching order, from elementary school to university, the more to the right were the professors. At the universities you had German nationalistic professors practically everywhere. So, the revamping of and the reorganizing of universities was, in itself, quite an undertaking.)

But while I would not have chosen Marburg, the State Department did, and instructions went out to that effect. And burying people in a church apparently involves under German law, or canon law, the consent of the family. And one had to track down the family of Frederick the Great, if you believe, and of Hindenberg, so that was undertaken. And one of our friends, one of the two officers, not Heinrich but the other one, whose name I forgot, was charged with contacting the daughter of the reigning – reigning is the wrong word – of the head of the family now alive, who lived in the Hohenzollern Castle in the French zone. And the daughter lived somewhere in the British zone. They were supposed to get in touch with her and, through her, then contact the father to obtain permission to rebury his forbears in Marburg.

So, this being highly confidential, he wrote guarded letters, and eventually met this lady in the British zone, explained to her what was involved and impressed upon her that when she writes to her father that she must be awfully circumspect because it’s top secret. So she did write to her father, and mindful of the fact that she had to be circumspect, told him that what was involved was a very important, but highly confidential, family matter. Well, our friend took off for Baden-Baden and got to the Hohenzollern Castle and came into the presence of the surviving head of the family of the Hohenzollern – I don’t know the name – a very charming, polite gentleman, and he explained that the ceremony was going to take place in the church in Marburg, but this has to be highly secretive and no public ceremony. It has to be done very quietly. And the prince, or whatever — the duke, or whatever he is — said, “Well, why Marburg, and why all the solicitude about secrecy?” He said, “Well, that’s what Washington, what the State Department, has decided.” He said, “Well, why does the State Department care where you marry my daughter?” To which our friend says, “For God’s sake, I don’t intend to marry your daughter. I came here to tell you that I want to bury your grand-grand-grandfather.” Well, the Hohenzollern had a great sense of humor and I saw with my own eyes a parchment scroll in which our friend was nominated as the First Body-Snatcher to the Court of the Hohenzollerns.

But that wasn’t all. Hindenberg’s remains also had to be taken care of. And he had a son who was a general, a Nazi general, in Hitler Germany and lived somewhere in the British zone. They got in touch with him by mail and asked him to come to Wiesbaden, and there our friend Heinrich was waiting, pacing up and down in the room because the man was way overdue. He was supposed to arrive on the train at, I don’t know, five o’clock and it was seven or eight, and he wasn’t there. And he started biting his fingernails. Eventually, he got a telephone call from the MPs and there he was told, “Are you the duty officer?” “Yes.” “Are you Mr. Heinrich?” “Yes.” “Well, we have a lunatic here. He is a nut. He is in a Nazi uniform, a Nazi general full of medals. He’s got a big Swastika on his arm, and he says his name is General Hindenberg. What do we do with that nut?”

Then there came the problem of the actual move, and the move of the sarcophagi was to be made simultaneously with the return of one of the greatest stamp collections in the world which belonged to the museum in Berlin. That too had been buried in the same salt mine and was to be returned. There the security was understandable because of its extreme value. And one of the two officers was in Bavaria, the other one was in Wiesbaden. They were very anxious to know how things were, in what state of repair – rather, in what state were these objects. And he went down to inspect, and there was a telephone conversation which, for reasons explained, had to be very guarded, and it went something like this: “Well, did the humidity affect them?” “What do you mean?” “Well, are they sticking to their casings?” And the other one said, “Well, we just opened one sarcophagus.” Anyway, the one was talking about the sarcophagi and the remains they found in it, and the other one was the stamp collection. And it took a while to sort it out.

Incidentally, being a member of military government and friend of the two men in charge, we had the privilege of viewing these things in the museum in the central collection point in Wiesbaden. And I can assure you that it was the richest, and most beautiful, collection we ever saw. It included also the head of Nefertiti, that famous head that has been so often copied – reproduced, rather – and which is in a museum in Berlin.

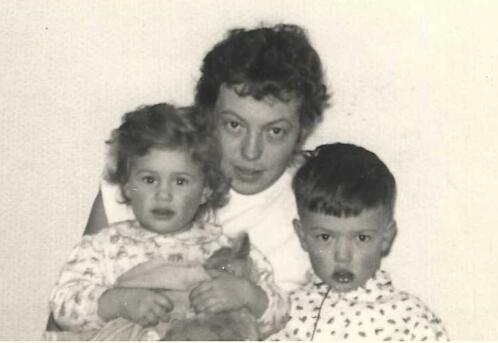

It is difficult to describe the social status one enjoyed being in military government in a relatively small city. Perhaps this will illustrate it. We once were at the opera, and the next day we talked about it to Irmy and she said, “Oh, I know that you were at the opera.” I said, “How do you know?” “You had been seen.” “What do you mean, ‘We had been seen?’ By whom had we been seen?” She said, “By somebody you don’t know.” “I don’t know the person?” She said, “You don’t realize but you are known in Wiesbaden.” Well, that gives you a bit of the flavor. [ed: Irmy was Irmgard Finsterwalder, who looked after Monica in her earliest years. Eventually, Irma left her employment with the Gruders, married Jürgen Stein, had two children with him, and became a very accomplished public school teacher. Jeanette called her “very modern,” a “rebel,” and an “amazing person.” The Gruders and Irmy stayed in touch and visited each other for the rest of their lives.]

As so often before, I have a problem with chronology or, rather, with dates. I think it must have been towards the end of ’48. No, it must have been after the summer of ’48, or early in 1949, when I had health problems. I had problems with my stomach; it was constantly upset. I was concerned and went to doctors and found some great, grosse légume [ed: literally “big vegetable,” but more usefully translated as “big cheese”] and, among others, we went to Professor Volhard, the famous internist in Frankfurt, who told me that what I have is a nervous condition. It was a polite word for a nervous breakdown, and what he prescribed was to go somewhere 1500 meters high or higher in order to assure entirely different climate. I could go there by car but then wouldn’t be allowed to touch the car until we returned four weeks later. He wants me in the first week to stay inside the hotel. The second week I may stick my nose outside and smell the air. The third week I may make small promenades, and the fourth week I can do whatever I please. Well, fine, I could do this, I said, in about four weeks. He said, “I may give you until the end of the week” and this was perhaps Wednesday.

So, sufficiently scared, we took off for a place in the foothills –- no, about one-third up the Mont Blanc. It’s a place above Saint Gervais, the only place which we could find open at this time of the season, and it wasn’t quite 1500 meter high, but it filled the bill. Mommy decided to come along of course. We had reliable help at home to take care of you, and we were terribly afraid that we were going to be bored to tears. And, as it turned out, we both slept every day in this fresh and bracing mountain air something like fourteen hours, dragged ourselves out of bed for the meals, and went back to bed, Mommy exactly as I did.

It did us a world of good and, oh, after about two weeks there, we had the visit of a colleague from Wiesbaden who made a detour to say hello to us and to bring us the good tidings of what was going on in Wiesbaden. Military government had just made a major change. I think it coincided with the appointment of Mr. McCloy to become High Commissioner and replacing General Clay as military governor and, in the process, they were decimating the legal division. And literally decimating means letting about ninety percent of the people go, and that included myself. In fact, I got my notice in Saint Nicolas de Véroce.

It’s interesting that this kind of information would have shattered me under other circumstances. I’m a worrier: where’s the next paycheck going to come from? And the relaxation there had done such wonders for both of us that we didn’t lose a moment’s sleep over it. We stayed our full allotted time. Mommy returned after three weeks because she wanted to be near you. I stayed one week longer, made a side excursion to Montana Vermala, to Crans, and then returned and, since I didn’t worry about getting another job, I, of course, got one. Immediately. I became the head of the political affairs division, left the legal division and assumed my new duties.

But, before I had left, I had made an application to the International Ruhr authority or, rather, to the U.S. Government Agency concerned with staffing the International Ruhr Authority. Let me explain. This was a body set up to distribute Ruhr coal and Ruhr steel to the war-devastated countries, devastated by the Germans, including their own. And the production was down. The result of the production was meager, and it had to be allotted. And so, the Ruhr Authority was created. Represented on it were the U.S., France, England, the three Benelux countries, and Germany. And it promised to be the surviving international agency that would remain after military government had run its course, so it struck me as desirable to be there. And the head of it, that is, the U.S. representative with a rank of ambassador, was Mr. Henry Parkman, who was a Republican but who worked constantly for Democratic presidents and who was a socialite from Boston — no, that’s the wrong word. One of his forbears rode the Oregon Trail. His father, I believe, gave away all the territory which became several parks in Boston. They were a Boston patrician family, and he was the U.S. representative of the International Ruhr Authority. And Marc Robinson was a friend of his, and he recommended me to him.

I applied for the job of political advisor to Parkman. I think I made my application long before the convalescent trip the doctor had prescribed but the government mills grind slowly, and my assignment came through after I was in my new job in Wiesbaden as the head of the political division. Well, needless to say that all my friends and my boss, Frank Sheehan, of course, were not going to stand in my way to get a job which had all the earmarks of being a career for the rest of my life, and I accepted and went to Düsseldorf, and with this began a new chapter in our checkered career. Mommy stayed behind with you in Schwalbach and I had to see what kind of housing I would get before moving the family to Düsseldorf.

Well, it began with my being assigned to – mind you, Düsseldorf was the British occupied zone, and the difference to the American zone became quite apparent after a few days there. The British simply had different standards and ran their occupation quite differently from the U.S. model. I was assigned to the Parkhotel, a very swanky hotel still in Düsseldorf, and there had my first taste of British mode of living for higher ranking officers.