Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 1A, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

…………………….

Well, we’re back in New York and once more I went to the office of the Council of Jewish Women, which was an interesting place. As I said before, the staff consisted of professional charity workers and there were some rather amusing incidents, of which I remember one. One young man came there and tried to inquire about a visum, an affidavit for somebody. And the girl, the case worker, gave him the necessary information and then asked, “And Sir, how are you set?” He said, “I’m all right. I’m studying at the university.” “Are your parents here?” “Yes, they are.” “And how is your father doing? What’s his profession?” “He’s a musician.” “Well, is he working?” The boy said, “Well, he’s having a concert in Carnegie Hall next week,” to which the girl said, “Well, we are always glad to hear when one of our refugee charges makes good.” The boy was the son of Arthur Schnabel.

I went there once more with a pal whom I befriended on the ship on the way over, and I forgot what the purpose was, probably looking for job opportunities, and, as we left, I saw a young lady. She struck me. She was very pretty. I looked at her and she looked familiar and, apparently, I looked familiar to her because she had that same expression on her face. I tipped my hat, and she nodded her head, and off we went in different directions. As I told you, the office was on Times Square and we sort of hung around in the neighborhood; and, about a half hour later, there I see that very same girl again. Again, I greet her. Again, she answers me. Obviously, both of us searching where we know each other from and, well, to make a long story short, we met in that same general area three times that day, that morning, in intervals of fifteen minutes or half an hour. And, finally after the third time, I said to my pal, “Listen, this is fate. I’ve got to see who that girl is,” left him, went over, and said, “Obviously, we have met before, but I must confess that I don’t remember where,” and the young lady confessed the same thing. We walked a bit together, decided that both of us had time to sit on this beautiful day on a bench in the park and tried to establish where we had met. Well, eventually after a conversation of about a half hour, we did establish that she had been that young lady who passed through the Hôtel de la Havane with an American visum, and her name was Jeanette Schestopal.

She confessed that she didn’t remember my name, but she vaguely remembered the face. I remembered hers, which was easier to understand because she was, as I said, a very pretty girl. Well, very elated, we had discovered where we had seen each other before. She told me that she was living in Astoria, which was an unusual place to live for a refugee. And how great was our surprise when we discovered that I too lived there, and that we got off at the same stop to go to our respective addresses. We made a date to see each other.

I believe several of our dates had to be called off or postponed because of job interviews that one or the other had to go to. But we saw much of each other for a few weeks. Jeanette who had lived, at that time, at the house of her aunt, the mother of Ruth Melzner, she had good reason of wanting to get out of there and as quickly as possible.

She informed me that she had accepted a job as a chamber maid in a kosher hotel, in a Jewish hotel in the Catskill mountains, in Sharon Springs. And she was leaving on a particular date which was close at hand. I, at the time, was about to give up the room I no longer could afford in Astoria, and I moved in with Dorly and Mutz Wang who, at the time, had an apartment in Manhattan somewhere.

She, Dorly, worked in a hospital, she had a job, but all this didn’t amount to enough to live on for themselves, let alone helping me out. But there was an extra bed, a sofa, and I slept there. I remember it was at that time that I lived on three dollars for about ten days. It was longer than ten days; it was closer to three weeks. Although the fridge was at my disposal, and there were things in the fridge that the Wangs had – it’s a curious thing. I wouldn’t hesitate today to rummage in anybody’s Frigidaire in the house of any friend but, of course, I — this is at a time when I do know that said friend can do the same thing in my fridge. You have no idea how hesitant you are, hungry or otherwise, in taking food when you know that you can neither pay for it nor replace it.

Well, somehow, I apparently survived, and I was very much in the dumps. I couldn’t get a job, there was no money coming in. The help from the Council of Jewish Women was minimal because I think I ran out of the initial time where they did help people with money. My friends were all in the same boat. And I know, being in a rather depressed mood, I wrote to Jeanette who was at the time already in Sharon Springs, working. She told me later that she was very moved by what struck her as a terribly depressed letter, and what touched her was the fact that I confided my concern, my depression in that letter to her. And, as a consequence, I received a telegram from her in which she asked that I call her long distance, collect. Even then she was the thoughtful girl that she has remained ever since. She knew I had no money so I should call her collect. Not that she made that much but she knew that she made more than I did. Well, I did call her and very hesitantly she told me that there was a job open. She hesitated very much to speak about it because it was a rather more-than-modest job. It was the job of a “helps waiter.”

That means, in these hotels where chamber maids and busboys and waiters were young Jewish kids who worked there for the summer in the Borscht Circuit and, in order to be kind to their feet for the work that was to come later, they ate before they get their guests and hired themselves a waiter to wait on them. That waiter was paid by contributions of a quarter, or what have you, by each one of the people he waited on, and he would get room and board from the hotel. That was the job opening. Well, I accepted enthusiastically. I believe I forgot whether Jeanette sent me the money for the trip, or I was able to borrow it. Anyway, I went up to Sharon Springs and became a ‘helps waiter.’

With that started a career in which I had a meteoric rise because the chief cook threatened me with a kitchen knife the first day when I came to the kitchen and very soon, they found that there was a better job for me to have and that was to be a waiter in the children’s dining room. In a Jewish hotel in the Catskills there was a special dining room where the little darlings were being fed under the watchful eye of doting mothers, each of whom came separately to the waiter in that room, asking him to take specially nice care of her particular child, slipping him a tip. Now these children were very nice and sweet, and I got along beautifully with them, as long as there was no mother around. As soon as the mother appeared, they became obnoxious and awful and terrible. However, I didn’t murder anybody and, in addition to serving children, who ate a little before the other customers, the officers of the hotel also ate there. That means the head waiter and the captain of the bellboys, the assistant manager of the hotel, and I believe that was it. And from them, too, I got a tip for the season. Incidentally, the tip I got from the maître d’ was an offer to either get twenty-five dollars as a tip for the season or pay him twenty-five dollars and he would leave me his car. And it is in that manner that I acquired my first car in the States. It was a Pontiac with, at the time, I believe a hundred thousand miles and I still ran it for sixty thousand miles more, at the end of which the World War had just been declared. By the end of that time the motor was still good enough for me to get about eighty or a hundred dollars for it.

The time Jeanette and I spent together in Sharon Springs was a wonderful one. I hardly spoke any English, very little — Jeanette considerably more — however, we had decided only to speak English with each other. And it’s a beautiful neighborhood. All the other kids were — waiters and chamber maids were — college kids. They were nice to us; we were nice to them. We had a very good time, we were very much in love, and it didn’t really matter that it was no great pleasure to be a chamber maid, it was no great pleasure to be a children’s waiter. But not only did we take it in stride, we had fun with it and somehow lived for the day. Our living quarters were incredibly bad, but we didn’t know better and I don’t know that it would’ve helped us if we had known better.

And at the end of the season, we returned to New York, and I believe I went from there to Lakewood, into another Jewish hotel [ed: the Hotel Grossman,] and then during the winter months I went to Florida. There were always a few months’ intervals.

In Florida I was hired into one of the kosher hotels as a captain of waiters. I went down in the car I had acquired, took along Otto Neumann [ed: the same Otto Neumann Viktor fled Vienna with, who remained in Milan when Viggi and Viktor proceeded to Paris] as a busboy. And, at that time, Florida not only did not have any organized unions in the hotel business, any union organizer found in Miami was run out by armed policemen on a truck to the frontier of Florida and most clearly told that he better not come back, with some cop shaking a gun into his face. And, usually, they didn’t come back. So, the conditions under which we worked there and lived there were incredibly bad. You paid for your own hotel room somewhere in a ninth-class hotel, you got a minimum wage (which I don’t know whether it amounted to a dollar a day,) and you got food, all you could eat, although there were limitations put on what you can get. Everybody, including the kitchen help, hated the boss so you got even with the stingy boss by eating the most expensive things if the people in the kitchen gave it to you. And otherwise, you lived on the tips you made.

And that particular hotel, called The Floridian, was quite an experience for me because it was the first time that I saw a large gathering of American Jews and it took care of dissolving one more of my preconceived notions. I discovered that Jews get as easily drunk and as often drunk as other Americans, that as guests they could be as obnoxious or as friendly as other Americans. I ran, for the first time, into the world of pills because people had their assigned tables. And the meals consisted of a huge menu for brunch which could be eaten from seven o’clock in the morning until two after noon, and that was the same menu – no meat, all milk products, all dairy products, milchigen meal – with a tremendous choice. And some people came in early in the morning for an hour breakfast and then later once again for lunch, some ate in the middle of the morning, and ate incredible quantities. But on each table, at each seat, there were mountains of pills which the people took for their health. At that time, I was amused by it. I never dreamt that there will come a day where I will do exactly the same thing myself.

I finished the season in Miami and returned sometime in March or April, or something like that, and then lined up a job for the summer, again in the same hotel in Sharon Springs where my career had started, but this time I got a job as a captain of the bellhops which was a desirable and good job, and as I said my career in that field was a meteoric rise. Here came the better job and came the summer. I went there and took great pleasure in inviting Jeanette to come and visit me, in the place where she had been a chamber maid the year before. She was now a guest in the hotel, my guest in the hotel. Oh, yes. I want to state that Jeanette had, in the meantime, while I was in Florida, she had started to work in beauty shops and had a number of, succession of, jobs and in the end a desirable one.

And she took time off to come and visit me. I borrowed from the maître d’ a Pontiac open coupé, very elegant car, to pick her up at the railroad station. We drove some thirty miles, and on the way, we stopped for coffee. And when we stopped the first time I engaged in a long monologue where I was musing over the fact that the costs of a room for myself, a single room for myself and a single room for her was certainly more than if you were living in a room for the two, and I went along in that vein. At the next coffee break I kept on talking the same way and Jeanette asked me, rather hesitantly, whether all that speech making amounted to a marriage proposal and I said, “Well, of course. What else?” Well, she somewhat complained that it didn’t seem to her romantic enough but of course I took out a handkerchief, put it on the ground, placed my knee on it and then asked her for her hand and we dissolved in laughter. And thus, we became engaged.

When Jeanette had returned from her work as a chamber maid, she had left her aunt and moved into a girls’ club. That was a rather interesting and very charming institution. Some rich Jewish lady had donated the money for a club that was run for Jewish girls, and it was run on the basis of very little rent money which you paid when you had it. And they gave you credit when you were out of a job until you would be again earning some money and paying off. It was run on a club basis, and I think Mommy will tell you about it. It was a wonderful atmosphere and there are, there were, a number of girls in that place, about two-thirds refugees from Central Europe. But there were also some American girls, and the camaraderie was such that there are some of the girls, some of the women, whom Mommy sees still today. This Clara de Hirsch home was on the East Side. Mommy will tell you the exact address. Somewhere off Lexington Avenue, and I was living, when I was in New York (not in one of the hotel jobs,) I lived on 91st Street West, between Central Park and Columbia Avenue.

By the time I came back from Florida we were in the spring of 1941. We knew that my father was getting a visum and we decided to wait the wedding until he would arrive, until after he would arrive and set out to find an apartment which we would rent, to occupy after we got married and Father would live with us, and we found such an apartment on Cathedral Parkway which was 110th Street, and rented it for, well, we knew approximately when Father was supposed to arrive, and we rented it for that time. It was way beyond our means but then our apartments have always been more expensive than they should have been. Somehow, we nevertheless managed and I felt very optimistic. I had explained to Mommy that if, between the two of us, we gained, we earned twenty-five dollars a week we could live like Gott in Frankreich [in the lap of luxury] — not that it was my ambition not to earn more than that but I thought that this would by all means, be enough and in fact it was.

So, things looked up a bit and, through the hotel union, the Unions of Waiters and Hotel Employees, to whom I had gone when I first came to New York, I got a recommendation for a job which would eventually lead to membership in that union. The Catch-22 with the union membership is that, in order to become a member, you have to work in a unionized place. However, you can’t work in a unionized place unless you are a member. So, a Catch-22. Well, the secretary of the union sent me to a nightclub which was across the bridge, across George Washington Bridge, on the Jersey side, and was actually a gambling joint which ran along Las Vegas lines. It had a marvelous floor show, a very excellent and cheap dinner (because they made their money on the gambling which was, of course, illegal.) But that’s where I was sent in preparation of becoming a union member.

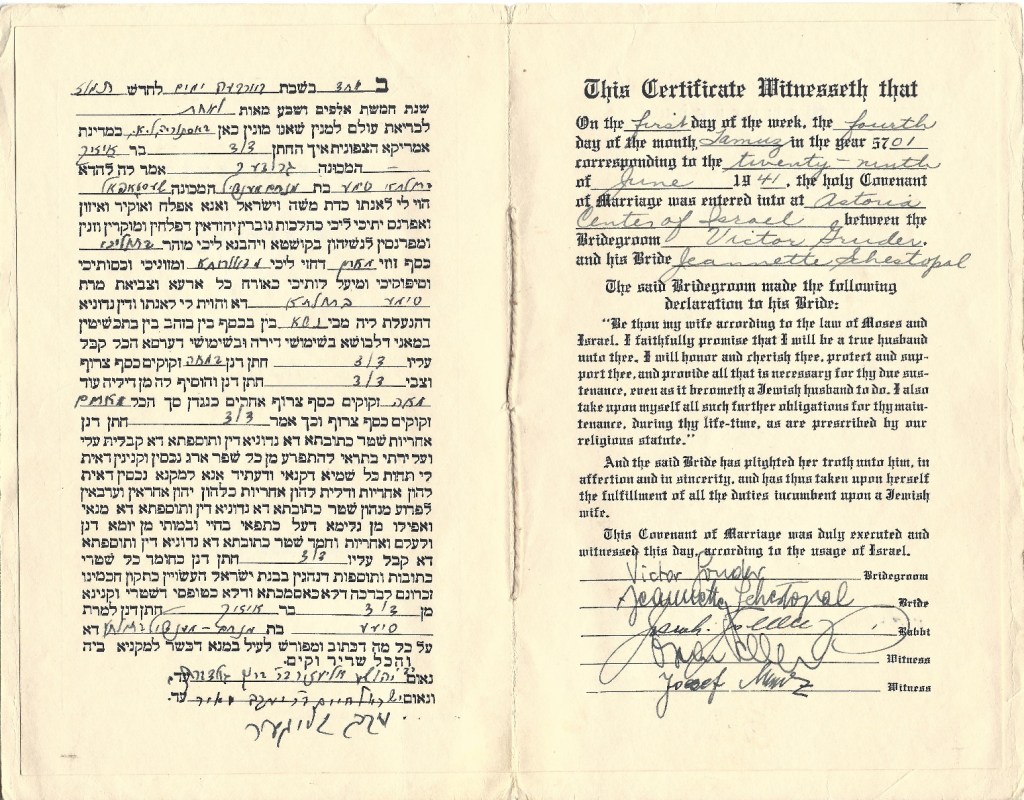

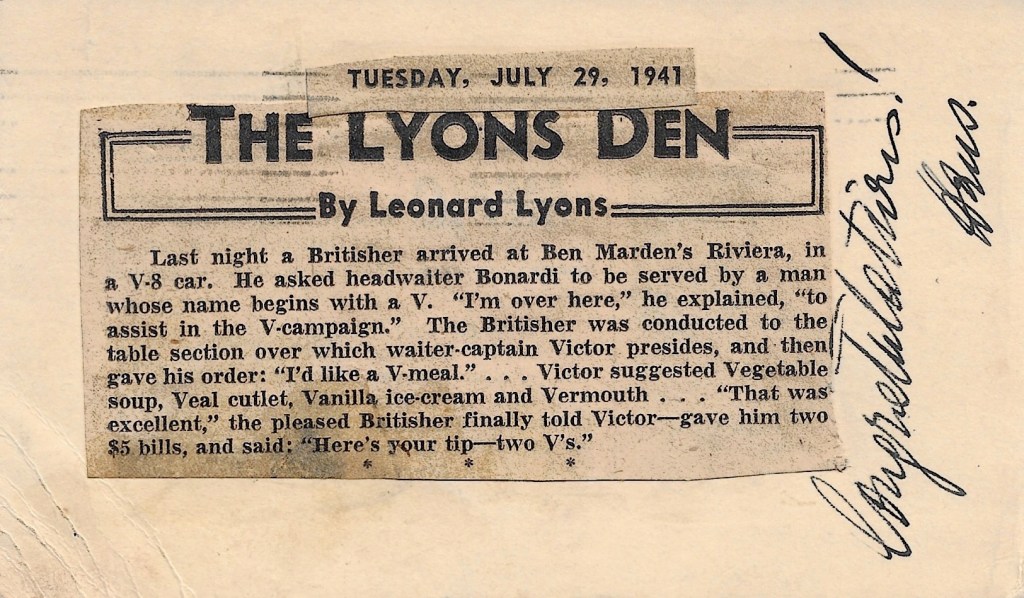

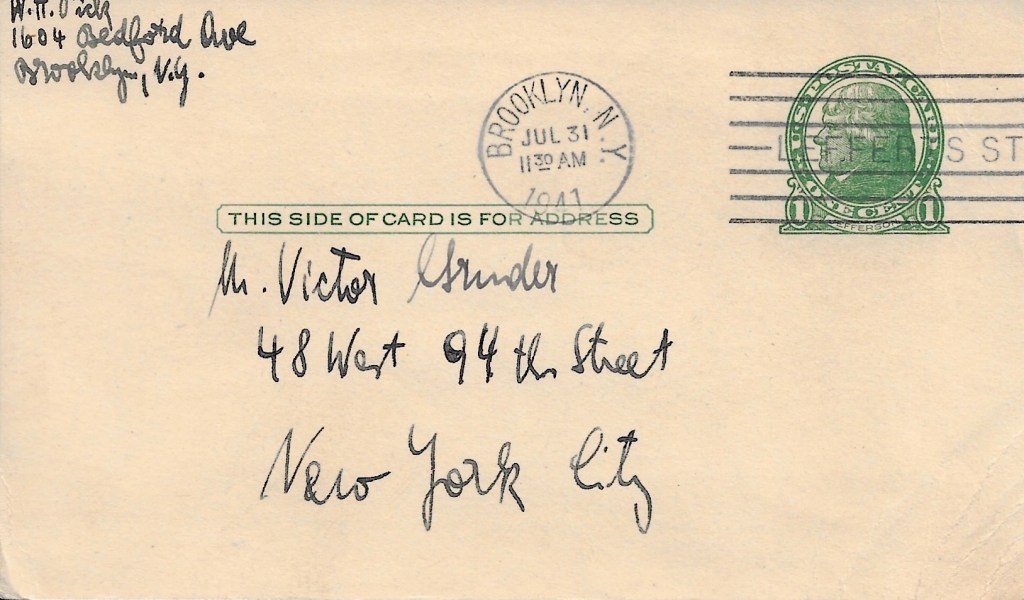

The timing of it is interesting. My father arrived around the 10th or the 12th of June 1941. We got married on the 29th of June ’41. The apartment was rented for that month. I don’t remember the exact timing. And, as it turned out, my job at Ben Marden’s Riviera materialized also at the end of June in a particularly dramatic fashion. As a matter of fact, I went for an interview and the man said, “All right. You can start,” and he gave me the date. And I said, “Well, sir, I’m getting married on that day.” So, he said, “All right. O.K. So, you can start on the next day.” And that was that. I started the day after our marriage. I started my new job, and I couldn’t afford not to.

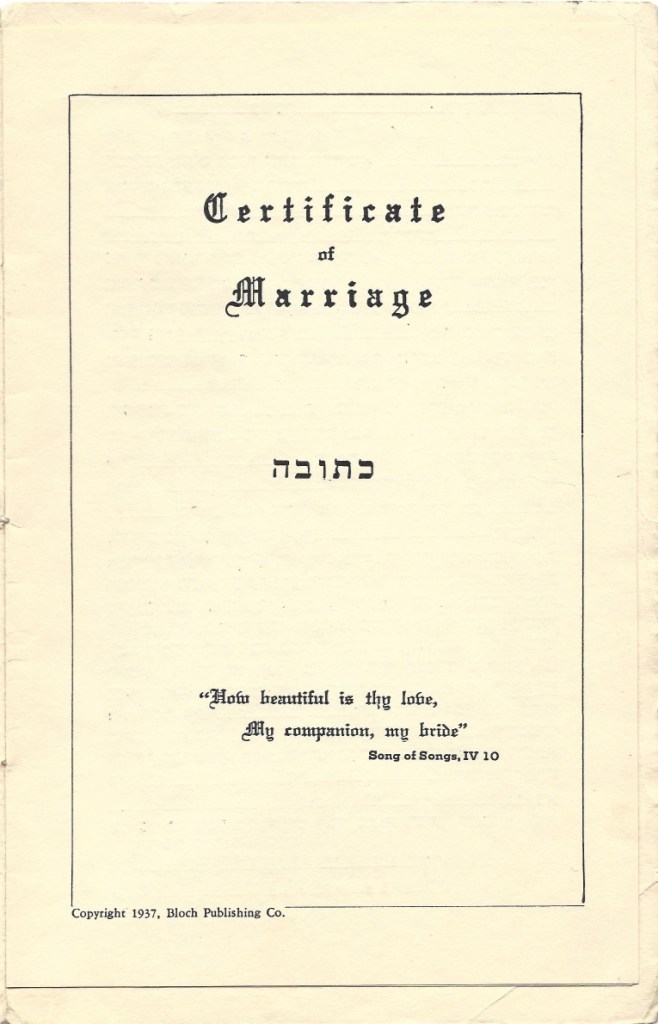

Our wedding was not exactly a social event. We got married by Rabbi Goldberg, for free I must say. And he had been paid some other way by once “lending me” some money from a diamond brooch of my mother which he acquired for next to nothing. At any rate, that’s where the wedding took place.

Mommy was attired for it in a new dress and one distant relative insisted that she must have a bridal bouquet, which the lady insisted on ordering but which the florist, of course, insisted on Mommy paying, and it took care of all the cash we had. As to the wedding ring, we had acquired that from a Viennese friend who had come to the States to get married and then was jilted by her prospective husband and she had a hot wedding ring on her hand, literally, which she let us have for seven dollars, which we paid in installments eventually. The wedding took place in the congregation of Rabbi Goldberg, in Astoria.

And after that, we had a luncheon in the Tavern-on-the-Green. I had reserved a table there and we arrived something like fourteen or sixteen people high at the place. I had worn gray striped pants and a black jacket from my father, and both of these things were made out of overcoat material, I think, because it was incredibly hot, and I was completely wilted. Mommy felt a bit better in the new dress. We suffered. Our luncheon guests – I shouldn’t call them guests because this was a luncheon which had to be Dutch treat. That is, everybody had to pay for himself because we were far too poor to pay for anybody else. We paid for my father and the two of us, for Uncle Toni and for Aunt Genia who had come from Los Angeles with a godchild or niece, or something. I forgot what the girl was, young girl. At any rate Aunt Genia had come all the way from Los Angeles because my father, very proud of the fact that his only son was getting married and to a girl he loved and admired very much, very grandly, had written to Aunt Genia and said, “I invite you to the wedding.” She came and stayed in a hotel and when she finally returned to Los Angeles, she wrote us an irate letter in which she expressed great dismay over the fact that, apparently, we did not know what is done because if you invite somebody to a wedding you pay. I said before that she was too dumb to realize anything. Of course, we could hardly pay her taxi fare to the Tavern-on-the-Green. In fact, we didn’t go by taxi. We went in my beat-up old car.

So, when I went to pay for the six of us (the head waitress realized that this was a wedding party and was kind of puzzled by the fact that I paid for six people,) she said, “And who is the bridegroom?” and she was quite vexée when I told her I was. And to make her feel better I told her, “If you get married, don’t do it on the 29th of June because it’s murder.” I apparently looked too wilted to be accepted as a bridegroom. One of the couples at the wedding was Jeanette’s rich aunt and her husband. That’s the aunt who owned five huge apartment houses in the Bronx and she actually managed to pay for – rather, her husband paid for — her and himself, and the wedding present was a ten-dollar bill.

Well, anyway we went home and collapsed, and Father held court with Uncle Toni and Aunt Genia and we, eventually, towards the evening, Mommy and I, we got out of our horribly hot clothing into the most lightweight wear we possessed. And it was, as I said, a terribly hot day so, fleeing both the company of the elders and the heat, we repaired to an air-conditioned movie on Broadway where we walked in and, within five minutes, we were deeply asleep. That was our wedding — not night, but evening.

The next evening, I reported to my job in Ben Marden’s Riviera. There began, then, the rather strange regime of our early married life. I went to work at about six in the evening and came home somewhere between four and six in the morning. Mommy worked during the day, and I had one day off. That’s the only time when we really saw each other, other than me coming home and she getting up. I was too tired to wait up for her and very often we didn’t see each other. I went to sleep before she got up.

It was a difficult time but, nevertheless, on Friday nights, which I think was my day off, we had our friends in, and since we didn’t have any money (nobody else did), we made very little, we treated them to a box of cookies. When we had done well with our respective tips, Mommy in her beauty salon and I as a waiter, we bought cookies for thirty-five cents a box, and when things didn’t go so well, we bought only a twenty-five-cent box. But it was a time in which most of our friends were, I believe all of them were, fellow refugees, and much of the conversation was an exchange of stories about our respective fates or, rather, how we were faring in our attempts to take a foothold in New York. And something very funny happened at the time: there seemed to be a sort of a contest between all present of who was worse off, everybody taking a certain pride of being the record holder of ill fate.

Life à trois wasn’t very easy. My father was not only a very sick man; as I told you, he was hard of hearing, and he was a most impractical person. While both Jeanette and I had adjusted to the do-it-yourself culture in the United States, it was hopeless to expect my father to do anything himself like polishing his shoes or what have you, or washing dishes, or anything of the sort. Which of course meant that Mommy had two jobs: working hard during the day and, when she came home, she had not only to make dinner for him and prepare breakfast for the next day, and leave something for lunch, but also had to take care of the apartment. It wasn’t easy. I don’t know, I don’t remember after how many months I worked in Ben Marden’s Riviera where, incidentally, the dinner consisted either of a, you could have either a roast beef dinner or a lobster dinner. It was called a “shore dinner.” The lobster was made with, was broiled with butter and the waiter was taking it apart in the dark while the show was going on and it was thus served to the guest, and whatever you could nosh in the dark while you prepared the lobster was a little perk of office. I ate a lot of lobster at the time.

Anyway, that came to an end. Rather, I gave it up because in the meantime the union had accepted me, and I was accepted for my first union job as a waiter in the Hotel Commodore. That was a regular, normal waiter’s job. By that time, I had become a professional waiter and it was a great advantage not to have to go every night, spend every night away from home. I had normal working hours at the Hotel Commodore and, while I came home late on days on which I had evening duty, there were days on which I had lunch duty and the evenings free. It was a more normal life.

And New Year’s Eve 1941 came around. War had broken out. We were beyond Pearl Harbor, and I was of course registered with the draft. And that New Year’s Eve in New York was a particularly lively one because wartime brings that sort of thing on. People live more intensely when they know they may be called up for the army or what have you, and New Year’s Eve, of course, was a particularly hard day in that restaurant. Well, Mommy and my father decided to come as guests late in the evening to wish me a Happy New Year. It also happened to be the anniversary of my mother’s death. And before I saw them, they watched me and, both of them, their hearts broke because I worked so hard. I felt very fine about working that hard because I made a lot of money that evening but, of course it was a long way to the kitchen, and you had a sweating brow. You earned your money by the sweat of your brow, as it were. That is when both of them determined I had to get out of that kind of business.

Mommy had the excellent idea of enlisting Bill Ebenstein’s [ed: see Letter 6 “Viennese Refugees”] help in persuading me to get out of this and study law, what have you. Well, anyway, Bill Ebenstein came, made a date with me, and he and I went to Schrafts.