Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 8B, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

………………

You can imagine the incredulity of the American mind to accept this kind of nonsense. And, when you looked into it, you found that the people who issued the license were the competitors in that very same field. That is, if you wanted to open a book shop, the other book shop owners had a say in whether or not it can be opened and whether or not you could exercise this profession. Or to be a barber you had to pass God knows how many tests and be an apprentice first and go through several stages of education before you would be entrusted with scissors. So, the U.S. military government set out to do away with this licensing nonsense, and we developed a series of professions in which it was quite clear that a license was desirable, necessary. You cannot let a doctor exercise his medical profession without having been tested and without being given a license. Doctors, lawyers, notaries were obvious candidates for licensing. And, what we held out for was that the license would not be issued by the competitors, so it wasn’t going to be the lawyers, such as the Bar Association, that would determine whether a lawyer could be admitted to practice law, but that it would be the Minister of Justice who would issue that license. Anyway, it was a major revolution.

I had a friend in the political division, I myself, and the Deputy Military Governor of Hesse (who took a particular interest in this crusade,) and we set out to popularize the idea that anybody can open a trade, a business, and let competition take care of whether or not he knows how to do it. He’ll go bankrupt quickly enough if he doesn’t serve the purpose right. Now, to the German mind this was an absolute, was more of a revolution than trying to talk about an abstract concept like democracy. Some people, some intellectuals, took to that abstract concept very easily, but to overthrow a system that has been in existence for decades, perhaps centuries, was a major undertaking. So, we set out, first of all, by military government fiat, we did away with the need for licensing, very much to the dismay of the various professions and various government people, and slowly instituted that list I spoke about, of professions which did require licensing.

There were some amusing fights about including or excluding certain professions and on the list that military government issued in Berlin were embalmers. The list had obviously been brought up by an American, and in America corpses are being embalmed before the corpses are being buried. Why this is done, it is as mysterious in America as the German licensing system was mysterious to us. And the Germans came running and said, “What is this embalmer business? We don’t embalm people in Germany except mummies for the museum.” Well, we eventually – we, meaning the people who knew something about German culture — got that taken off the list.

But we didn’t only want to revolutionize Germany of the American zone; we wanted to have the public on our side. This was a country rebuilding, and we wanted to popularize the idea of competition, the idea of freedom from licensing. And we also wanted to popularize participation of the population in the process of law making in government, the concept of civil participation in the democratic process, and we encouraged the people on the local level to institute town meetings, town hall meetings. We had meetings in various America Houses, which were cultural buildings run by the U.S. government with U.S. government funds, and we held speeches in these town meetings. Of course, only those of us who could speak German did so, and I was one of them.

I must have held, in the course of about two years, something like a hundred and fifty to two hundred public speeches. And you develop a certain spiel about it. The Germans were totally unused to participatory democracy, and it was fascinating to see the audience. The audience looked at you. You know, when you speak to a large audience you learn very quickly that you, actually, it comes off better if you speak to one single person. You sort of stare at one person and start talking to him. And, when you do this for a while you see that person, when he is a German, becoming uncomfortable and then he starts nodding his head. That is, he is nodding agreement. And, if you then look at somebody else, it makes you realize, eventually you get the whole crowd to agree with the speaker.

Well, then we invited questions from the floor. They were slow in coming, because, as I said, the people were not used to it. But, usually, some member of some guild or profession, spoke up, defending the German system and telling us how wrong we were, and it was then my business to answer that person. And I always made sure to have the last word because the audience invariably agreed with the last speaker. Whether he was saying the exact opposite of what I had said, they had agreed with him too, and then I discounted what he said or opposed what he said, and they agreed with me again.

Well, in order to bring the thing home, I had to find some subject which would tickle them. Humor in a public speech in Germany was not something that Hitler or any of his speakers had gotten them used to. So, if you got the people to laugh, you had won, and I had picked what to me seemed as two extreme examples of particularly ridiculous licensing requirements and made these two things the butt of my irony. And they were pharmacists, on the one hand, and chimney sweeps, on the other. Well, this needs an explanation, obviously: pharmacists, obviously we agreed – we, military government agreed — that the pharmacist has to be a trained person, has to pass tests, and has to be licensed to be a pharmacist. What we opposed was the idea that the owner of a pharmacy, together with other owners of pharmacies, would pass judgement of whether a yet third pharmacy in that particular township could be opened. The original German law said one pharmacy per 50,000 inhabitants. You had 50,001 inhabitants, two pharmacies. 49,999 inhabitants, also, only one pharmacy. Now that, we opposed. And there were two kinds of patents, called une patente, rather. One was a matter of heritage. You owned the right to run a pharmacy and you passed that right on to the widow and to the children and that particular owner didn’t need to be a trained pharmacist. He could hire one, hire himself somebody who was a trained pharmacist, male or female. But you couldn’t become the owner unless you had such a patent. Now that we opposed. The other possibility was to get the right to open a pharmacy for each 50,000 population, but that was only for a lifetime. Now, pharmacies were, as you can see from this kind of tradition, absolute goldmines. The pharmacist was often the richest man in the community. No wonder. He had an absolute monopoly. We, being used to the American system where you have a drug store, where you hire yourself a pharmacist, and you dispense medication, well, we were for free competition. We fought with the Ministry of Justice for months and years, because they were — the main argument was that the control of pharmacies in number was designed to stem any illegal traffic in drugs (that is, in addictive drugs,) and, if we opened this up to competition, we would get all — the drug addicts would corrupt the pharmacists, and chaos would ensue. I used the pharmacies as one example of what I considered an outrage and described it to the people. And, since I had the laughs on my side, the pharmacists in the audience fumed.

But much funnier than the pharmacists were the chimney sweeps. A chimney sweep in Germany has a position which is a unique in law. The law prescribes that if you have a chimney in your house (depending on various kinds of chimneys which are described in the law by name,) they have to be swept, cleaned, once or twice a year, depending, and the law prescribes it. Now, the guild of chimney sweeps was established, and they divided the territory of an area, and there was a chief, Kreis, chimney sweep, who was a master chimney sweep, who had helpers, assistants (who were also already past their test period and were chimney sweeps,) and then apprentices who had to study this very difficult science for many years before they could become assistants. But you could only become chief chimney sweep if the old man died off, because there was only one of them. Why was this so? Because it was a very desirable thing. That chimney sweep picked the time when he would come to your private house and sweep your chimney. He would inform you that he would come on that Tuesday at this and that hour and would clean your chimney. You had to tolerate this arrival because the law says it has to be cleaned, and you needed to have proof of that cleaning. But you couldn’t choose who would clean your chimney. He would choose when he would come to you. Now, we didn’t see any particular need to have this art perpetuated by tests and what have you, but by God, you want to have chimney sweeps — fine, but let the customer determine which chimney sweep he wants to call.

Now, this was a revolution which the chimney sweeps were absolutely up in arms. And, since I used the chimney sweep as a glaring example of the stupidity of this licensing system, I was known amongst the chimney sweeps in the whole of the American zone. Newspapers reported about the speeches, and since it invariably got a laugh when I said that there is this 78-year-old chimney sweep who was no longer going on any roof, but he’s got the monopoly to tell you when he can walk through your bedroom to clean the chimney, and you have no choice in the matter, and isn’t that outrageous? Oh, yes, the reason why he could be 78 years old: the Nazis had taken off the limit which the original German law put on it, where they retired the chimney sweeps at the age of, I don’t know, 65 or something. But Nazi Germany was so short of people who could function as soldiers that they kept old people in jobs indefinitely, so they took off the legal limit and so, chimney sweeps were old men and an easy target for irony.

Well, this led to several interesting experiences. At one time, I was holding a speech up in Kassel, and the Elegants and Mommy sat in the audience.

We were going somewhere afterwards so they listened to this. They sat in the first row, and I was holding my speech, by then a routine affair, and then I asked for comments. And one old man got up and he limped to the dais, came up there and said, “I am the Chief Kreis chimney sweep.” Well, there was pandemonium. Everybody laughed and Mommy and the Elegants were rolling in the aisles. I was supposed to stand up there and make a serious face, because I made it clear there’s nothing personal in this. I had to make it clear that there was nothing personal in it. It was just an example given. And this man was absolutely trembling with rage, explaining that he is 78 years old, or 72 (I don’t know) and he does still go on the roof and took it very personally.

That was one experience. And the other experience was that one day my secretary walked into the office and said, “There is a very strange man outside who wants to see you.” I said, “Well, what’s strange about it?” She said, “He gave me his wallet and the telephone number of his wife, and told me that if anything happens to him, I should, as a fellow German, please call his wife, and tell her.” What on earth was this all about? Well, he came in and stood there at attention, introduced himself by name and said that “I am the secretary of the Chimney Sweep Association of Hessen.” Then, he opened his coat, bared his chest and says, “You can have me shot on the spot, if you wish, but I will tell you what I have on my mind.” I invited him, very politely, to take a seat, and told him somehow that we are not in the habit of shooting people on the spot or otherwise and I am there to listen to him, that’s my job, and what has he got on his mind? Well, he was certain that he was not going to leave that place alive, or perhaps being arrested as a minimum.

And he explained to me, at great length, that they had a pension fund. This pension fund was depending on the contributions which had been being paid for years, and that our lifting the licensing requirements played havoc with their pension fund. He had an absolutely justified problem. Not a grievance, but a problem and I took that problem very seriously, talked with him for an hour and mapped out the possibility how this could be — that pension fund could be saved, and, discussing this with him calmly. But he was so surprised when he left that he said, “You know, I had an entirely different concept of you. You know, we have read about your speeches and heard about you, and I expected something quite different.” As a matter of fact, I said, “Well, do you tell your fellow chimney sweeps that I’m not an ogre and that I’m perhaps somebody one can talk to.” He said, “Yah, I’m not only going to do this. We are going to invite you to our next meeting as our guest speaker.” Needless to say, that I did not cherish the idea of speaking in front of two hundred chimney sweeps who had it in for me, but it was a nice turnabout, this man who considered himself condemned.

One interesting sidelight on this activity: I had spoken on the radio for about a year, twice a week, I think it was. I had held these public speeches all over Hessen and my voice was known to some people, my face, my manner of speaking, and during all this time, I did get newspapermen or from members of the audience after the session was over, I got compliments, “Where did you learn to speak such excellent German?” to which I had a standard answer, “I went to school in Austria.” Perfectly true. It was only a single time where one man, who would turn out to be a half Jew, asked me whether this was my mother tongue. Otherwise, thousands of people never once had the idea that I was speaking my mother tongue.

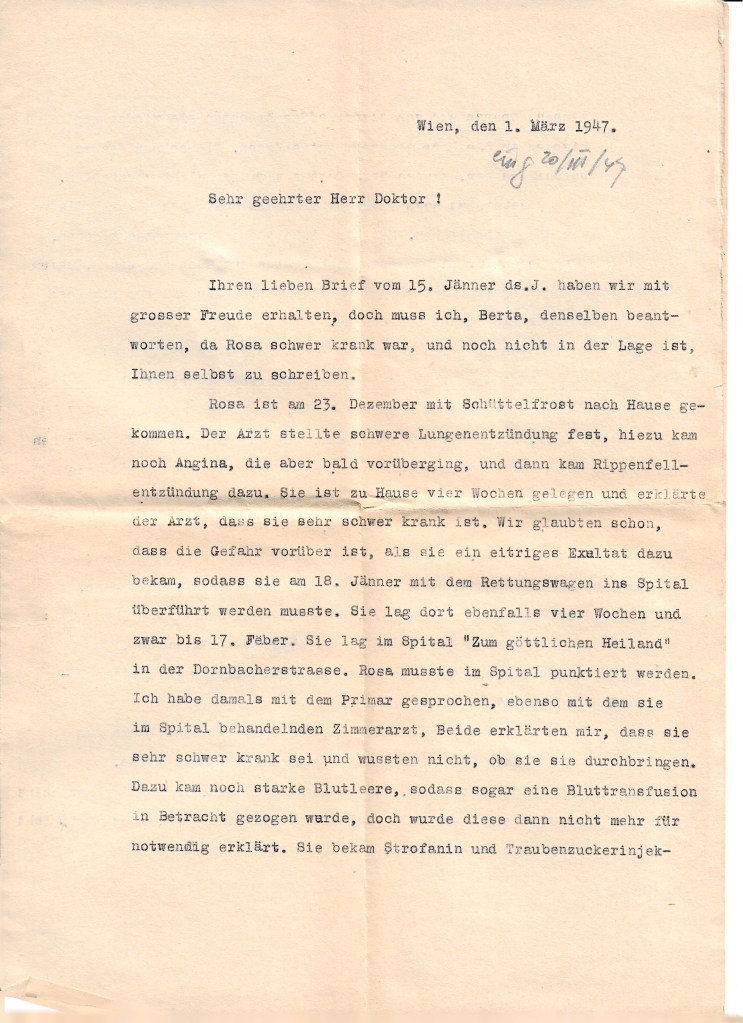

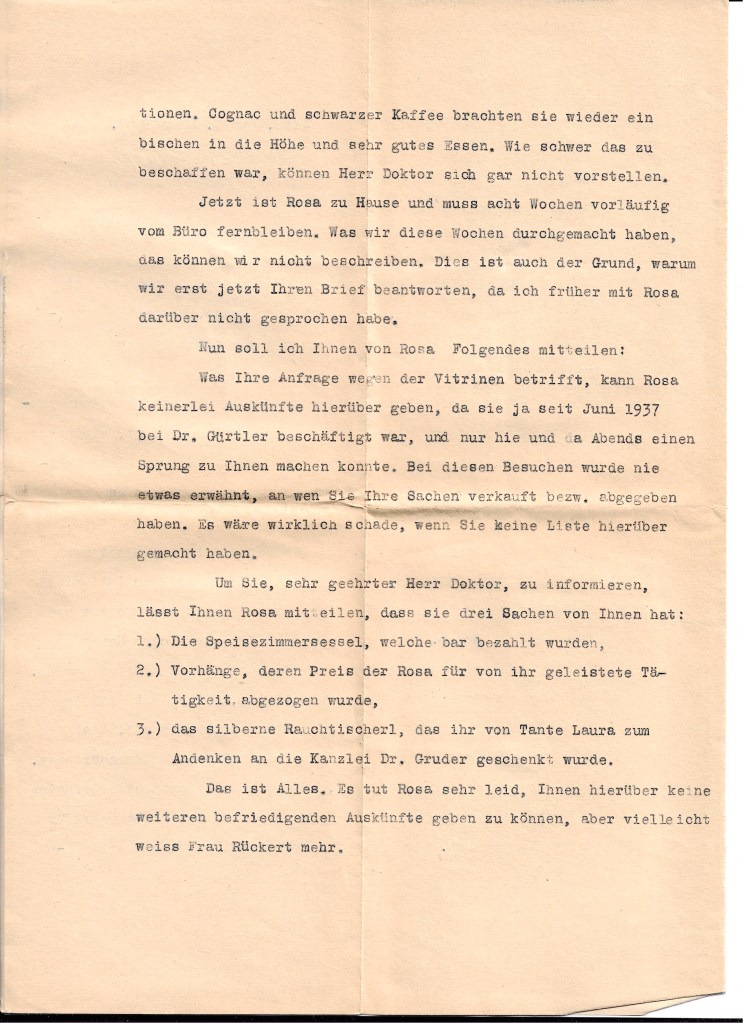

Now, let’s go to something else. I should like to tell you about my first trip to Vienna. That happened, I don’t exactly know the month. It happened, of course, after I was already assigned to Wiesbaden, and before Mommy and my father came to join me, therefore, it must have been sometime like September, or so, 1946. The time when this happened is important. I had arranged, with the army — that is, you know, at that time things you could do were incredible — I arranged with the authorities in Wiesbaden, the people who I worked with, to lend me a truck with a driver. With that truck, I was going to drive to Vienna to recover things which I expected to find there, things that belonged to my parents, to myself, which had been, before their departure, distributed to various friends, and generally to see what I would find in Vienna. I have no exact recollection of that trip. We must have slept over at least once, and we arrived in Vienna. Remember, I told you, that at that time, we all wore uniforms, American uniforms, and, instead of a rank on the arm, we had a big “U.S. Civ”, for “U.S. Civilian,” on the sleeve.

I went to the billeting office and was directed to one of the hotels in Vienna, not a, a pretty old hotel, not a luxury hotel –yes, a luxury hotel but an old-fashioned one. And I arrived there in the late afternoon. I went in, saw the portier who informed me (and all this happens in Viennese. I did not make any pretense of not understanding it, spoke Viennese myself,) and was told as far as the footlocker is concerned — I had a footlocker full with food with the intention of bringing this to people like Karli (whom I hadn’t met yet, but of whose existence I knew,) [ed: the husband of Jeanette’s sister Lydia] and perhaps (if she survived) our former office directrice, and what have you. So, I had a heavy footlocker and a suitcase for myself, and the driver had one. And the portier informed me that I would have to carry my footlocker to my room myself. Well, this is how my lovely stay in Vienna started. I said, “What do you mean? Where is your bellhop?” “Oh, he knocks off at five o’clock,” and it was past that hour, and “I have nobody to take it up.” I said, “What’s wrong with you?” Rather outraged, the man pointed to a crippled arm, or rather an injured arm, and said he was an invalid, and he couldn’t carry, and I said “Well, I’d like to see the manager.” A fairly young manager came who also informed me that he has nobody to take the suitcase up. I said, “Well, what’s wrong with you? You are not crippled.” That, as you can imagine, endeared me to him. And he turned to two men who were guarding the cars parked in a parking lot in front of the hotel. And, he said, “Karl and Ferdl, take that suitcase up.” And one of these guys turned to me and told to me, all this in Viennese slang, “That will cost you some packages of cigarettes,” whereupon I told him, “Put that suitcase down. I’m not having my tips dictated to me. If I feel like giving you a tip, I will.” Well, the director whispered to them to carry it upstairs. I gave them much more that they expected by way of cigarettes and tip.

And I found myself in the smallest, most miserable room that they could conceivably find in that hotel. It was dark and at that time, the electricity was erratic. You sometimes didn’t have any for hours. It was undesirable, a most undesirable room because the electricity did cut out, and it was not a very agreeable night. The next morning, I went down, the same portier at the desk, and when I ordered my breakfast, I told him, “Would you connect me with the City Hall?” “Who should I ask, whom would you like to speak?” “I’d like to speak to the mayor.” He said, “Which one?” You see, there was the Lord Mayor, and he has several deputy mayors. I said, “I want to speak to the Lord Mayor, General Körner.” Well, there was a pause, and then the portier asked “And who should I say is calling?” I said, “Just say Vikalu is calling.” Well, there was no further comment from the portier. He connected me, called me from my breakfast and I was connected with the office of General Körner, who, in a way, was my godfather. He was an Austrian General during the monarchy and my father had converted him to Socialism. And he was the man who escorted the last emperor of Austria, Karl, out of the country, to his exile. He was, to me, something like a grandfather, godfather, and a very impressive man. Incidentally, he comes from a very illustrious family. One of his forebears was a famous German poet, Theodor Körner. And, well, back to the portier. When I finished the call, the portier said to me, “Yes, Herr Doktor.” I had advanced in my status. I said, “I now would like to be connected with the Chancellery, would like to speak to Vice Chancellor Schärf,” whereupon he said, “Yes, Herr Baron.” I had further advanced in my status. He undoubtedly listened into that conversation and heard that there, too, I had made an appointment for a visit, for an interview, a rendez-vous with the Vice Chancellor.

And then I met Karli who came to the hotel and it’s the first time I met my brother-in-law.

And he was very excited. So was I. I brought him news from his wife whom I had last seen in London, as a civilian worker in the defense industry and who by then was working for the U.S. as a censor in Germany. I don’t exactly know, I no longer remember what the censors were censoring but it was a job, and she had, by then, decided to leave England, and took that job, and that brought her back closer to Vienna.

And eventually, she had herself returned to Vienna as part of her employment. But, at that time, she was still in that place near, in a place near Munich, and I met Karli. Well, that was a typical Viennese experience. Karli had been by trade an electrician. Therefore, I was rather astonished when he told me that — and this I have to tell you in Viennese because it doesn’t come up in any other language. “Ich habe mich mit meiner eigenen Kraft vom einfachen Arbeiter zum Angestellten hinaufgearbeitet.” [“By my own strength, I have promoted myself from worker to salaried employee.“] The distinction between Arbeiter and Angestellter is almost untranslatable. Arbeiter is blue collar. Angestellter is white collar. It says nothing about their respective income. Very frequently the Arbeiter makes considerably more than a lowly Angestellter, but he considered that he had really achieved great increase in his status by becoming an Angestellter. Incidentally, he was an employee of the Social Security outfit. After our conversation, I left the hotel to go to one of my appointments.

The interesting thing about the hotel was that when I returned in the evening, nobody had said a word to me except that they had changed my room for which I hadn’t asked. I hadn’t insisted on a change of room, but they had changed my room, and I found myself in the Imperial Suite. It was quite a change from the room I was originally given. I’m telling you this because it’s typical for Vienna. Now, then, and as it always was.

One of my next visits was to our former office directrice. I rang the bell, and an old woman opened the door, and I asked whether I could speak to Rosa, and she told me she was Rosa. It was quite a shock. I guess my shock must have shown because she cried. As I looked around, I saw the apartment furnished almost entirely with the furniture of my Aunt Laura and to preclude any questions, she immediately volunteered that Laura had given her that furniture to keep for her until she would return from the concentration camp, if she was arrested — which she of course was — and that she, Laura, had told her that if she doesn’t come back, she can keep the furniture. Well, I did not insist on anything. In fact, I didn’t as much as comment on this very unlikely story. I accepted the one, single small rug which she said she had been given by my parents to keep and, I believe, also two paintings. I forget which. I think one was an old man, something that Henry has, I think. I left and never got in touch with her again. I was so disgusted that I didn’t want to see her or hear of her again.

I made another visit to a Party friend of my father to whom he had turned over his and my library before my father left Vienna, and the man greeted me with great pleasure. And yes, indeed, he’s happy to have survived. Yes, also the books had survived, but they were all mixed up at his home, and he informed me that as far as the books on socialism were concerned, he had surely, and my father would undoubtedly agree, given them to the party headquarters. As far as private books were concerned, or rather the non-political books, they were mixed up with his own, and would I pick them out since I undoubtedly know them? I picked one book and he told me, well, I must be mistaken because he remembers when he bought this one. I made another stab at it and had the same reaction whereupon I gave that up, picked one small volume of Arthur Schnitzler and left, again without ever seeing this great human being again.

And so it went. I saw one leading socialist woman who had some very nice things to say about my father, and then she confided in me that, can I imagine, there was a socialist lawyer who had written from Switzerland asking what the situation in Vienna was for a Jewish lawyer. And she invited me to share her outrage about the enormity of such a question because, after all, this man is supposed to be a socialist and, as such, should know that a socialist doesn’t know such a thing as a Jew. Well, that was the end of that particular relationship with that woman.

The only pleasant experience I had during that time was my visit with General Körner who told me I should tell him of what’s going on, what I had experienced, and I very modestly looked up to the man, I said, “Well, how was it with you? What was Vienna like?” And he said, “Look. I’ve been living in this small country, within the walls of this small country. I survived, as you can see, but you have been out in the big great world. You’re the one who has something to tell.” That sort of describes the man. He also said something very interesting about, I asked him what it was like to be a mayor of a city occupied by four occupying powers. And he said, “Well, nothing really very difficult about that.” He said, “You see, I’m a general and the heads of the four occupying powers are generals. As you know generals go by rank, regardless of their nationality. I happen to be senior to all of them, so I’m being treated very nicely by everybody. The only difficulties that arise from time to time are a matter of mentality.” And he related that shortly before I came, he had a call from the Russian Kommandant, Russian head of the occupation power, who asked him how many heavy cranes he — there were in the ninth district. And Körner answered him that he didn’t know, but he would find out for him. And the Russian general was outraged. “What do you mean? You’re the mayor of the city and you don’t know how many cranes you have in the ninth district?” Well, as Körner said to me, “You see, how do you explain to a communist general, a Russian general, that a mayor in a Western country does not necessarily know how many cranes there are in the ninth district?” That was the sort of thing that he found slightly frustrating, I guess.

I made a visit to the university to see whether I could, or I should, pick up my degree. [ed: his Master’s degree in law] And I saw the university, I smelled it, and after a few minutes of this, I turned around and decided that not only was it not worth it — I wouldn’t do them the honor to pick it up. I don’t want this to sound false. It would have entailed preparing for and making one small, short exam on Roman Law. I would have had to prepare for this. I would’ve had to discuss it with the dean of the jurisprudence department to whom I had a recommendation given me by Ebenstein. And it was all that, that I didn’t wish to face, notwithstanding the fact that that dean, with whom I had corresponded and to whom I talked on the telephone, had made it quite clear that it would be a mere formality. It was that formality that I didn’t want to go through, sitting as a candidate in front of three professors, each one of them most likely being, or having been, a good Nazi.

There was one more experience in Vienna. My friend, Maria Reining, who as I told you at an earlier occasion, had become a famous singer. And I of course wanted to see her. She was in Vienna by that time, married to a Swiss businessman but she had been singing throughout the Nazi time, although or perhaps because she was married to that Swiss with no political undertones. And I went to the opera and heard her in Tannhäuser and was invited by her, there was a great reunion and Wiedersehen mit Wiedersehensfreude [joy of reunion]. She invited me to come to the home of Max Lorenz who lived near the opera and who himself was a Wagner tenor.