Above you will find a digital copy of Cassette 5B, recorded by Victor Gruder. What follows below is our best efforts at transcribing the contents of the recording. Occasionally, an informal translation or editorial aside is inserted in square brackets ([ ]) for clarity or context. Anything underlined is a hyperlink. As with the title of each “Letter”, they are our addition, and we deserve all blame for incorrect statements or assumptions.

…………………..

Viggi Kalmus and I started out for Paris. We went to a hotel. You know at that time one didn’t rent a room in some private home. One went to a hotel where they had — a residential hotel (there was nothing particularly residential involved other than the fact that you didn’t rent by the day or by the week but by the month.) The one we moved into (I forgot how we got there,) was called Hôtel de la Havane and was on Rue de Trévise, slightly off Rue de Lafayette, in the area of the Folies Bergères, and there were a number of other Viennese and German refugee men there. We were a group of about sixteen who lived there, under the watchful eye of Monsieur Voisin, the owner. We had no money, and it was almost impossible to earn any. Viggi Kalmus was luckier than I; he landed a job with one stamp dealer. And, of course, we not only shared a room, we also shared whatever little money we made. Our expenses consisted mostly of the hotel room and food.

Now food was cheap at the time in Paris. You ate in a prix fixe, a whole meal for three francs, a slightly better place for five, with vin et pain à discrétion. Well, the way we ate, it was more indiscrétion. As a matter of fact, the waiter started to know us and started removing the bread when we came. But we mostly ate only one meal a day — had a croissant with coffee for breakfast and at lunch time we would buy ourselves one of those rich Tunisian or North African sweets, not because we liked them so much but because they were cheap and filling.

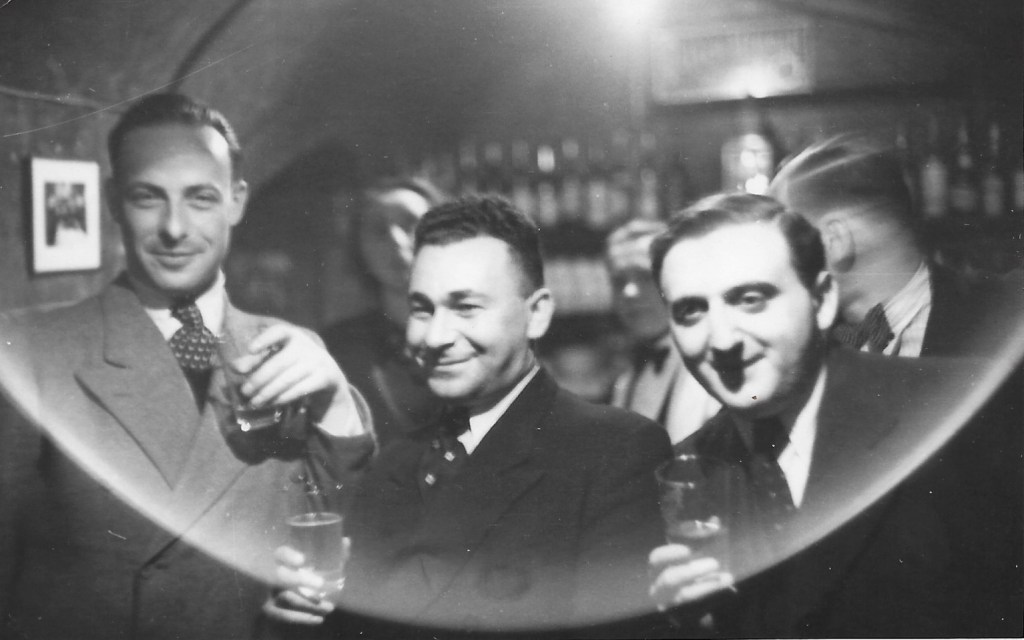

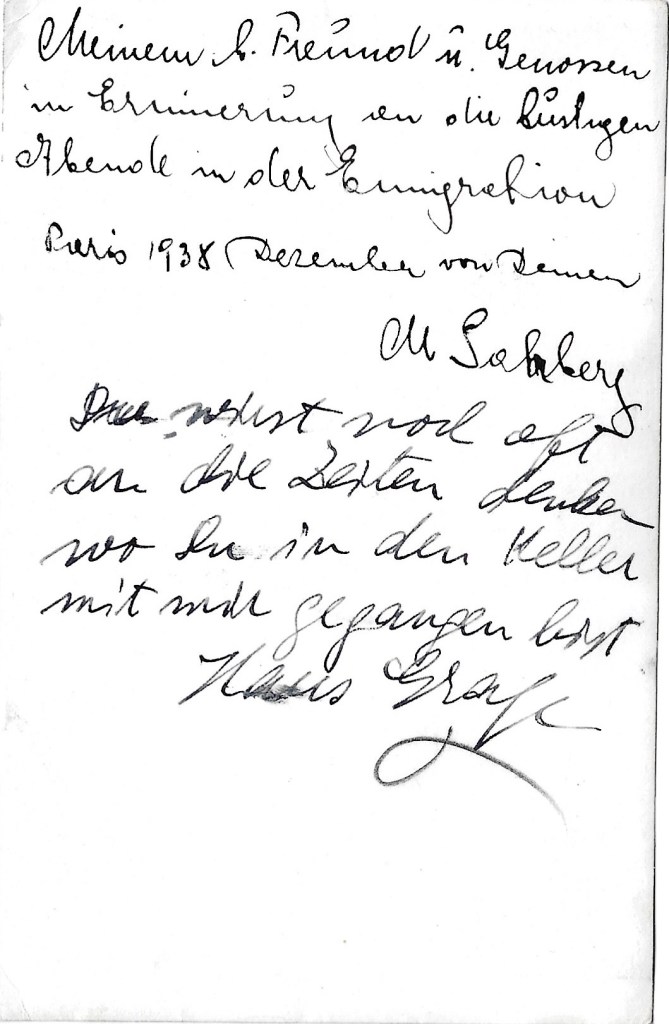

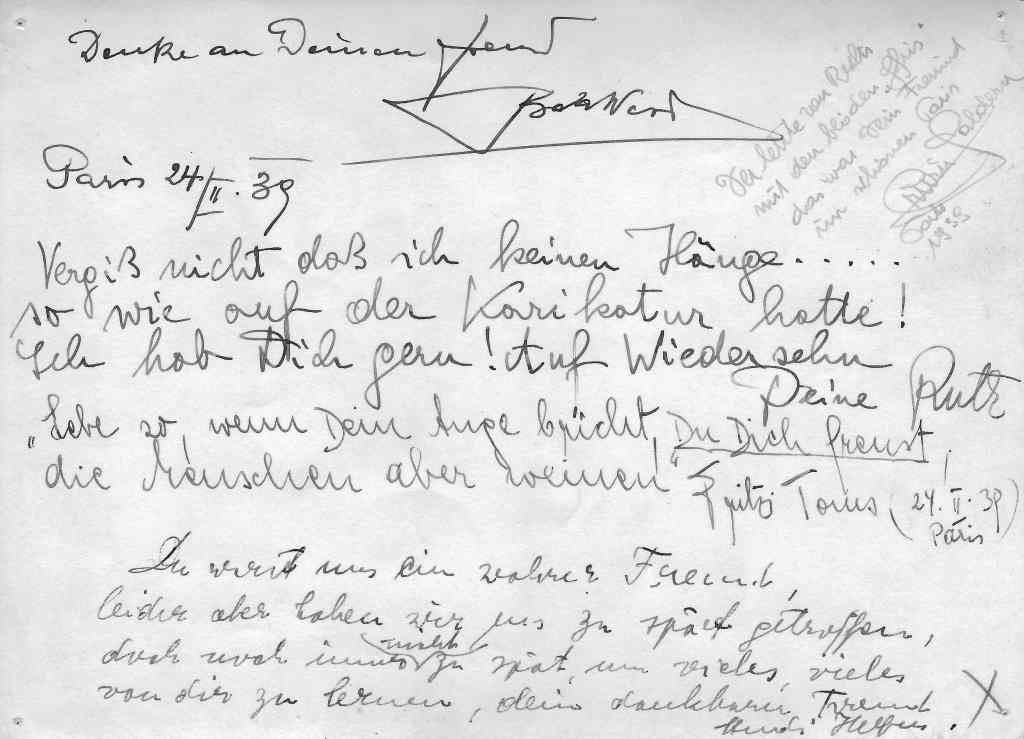

Well, I had tried my hand at a number of things. I gave German lessons to one industrialist and also to the son of the hotel owner (who took it off my hotel bill.) You know the funny thing is, it never occurred to me at that time to wonder why a French industrialist would, at the ripe age of forty or so, suddenly start taking German lessons. He was, apparently — he showed more foresight than most Frenchmen and I find it curious today that it never struck me as curious at the time. Well, I wasn’t earning much. We augmented our income by my entertaining in some German clubs. That is, some German Jewish refugees had some loosely knitted social organizations and clubs in the back rooms of some cafés and there I would, with Viggi Kalmus at the piano, sing little ditties which I had myself written or which I shamelessly copied from some Viennese entertainers. It was usually only a few friends, but it was important experience which came in handy later.

But after a few months of this I got word that my father had not only gotten out of prison but that they were able to get a visum for France, both my parents, and they would be arriving – I must confess, I don’t remember exactly the date. My father’s release, or rather his arrest and release, are a story in itself. He was arrested the day after we, that is Otto Neumann, Viggi Kalmus, and I, had left for Italy. The next morning police were in our house; had I been there, I would have been arrested with him. And, luckily, he was again put into a police prison, not into a concentration camp. And by some lucky coincidence one lawyer, a fairly young man who had been a Nazi (or rather, a lawyer defending illegal Nazis,) had at one time asked my father, who was by many years his senior, for some advice about political trials (for which my father was well known,) and my father had given him some information. That man, after the advent of, after the Nazis coming to power, either noticed or had heard that my father was arrested (he had meanwhile become a prominent Nazi official,) and on his own volition, intervened and obtained the release of my father who was sent home.

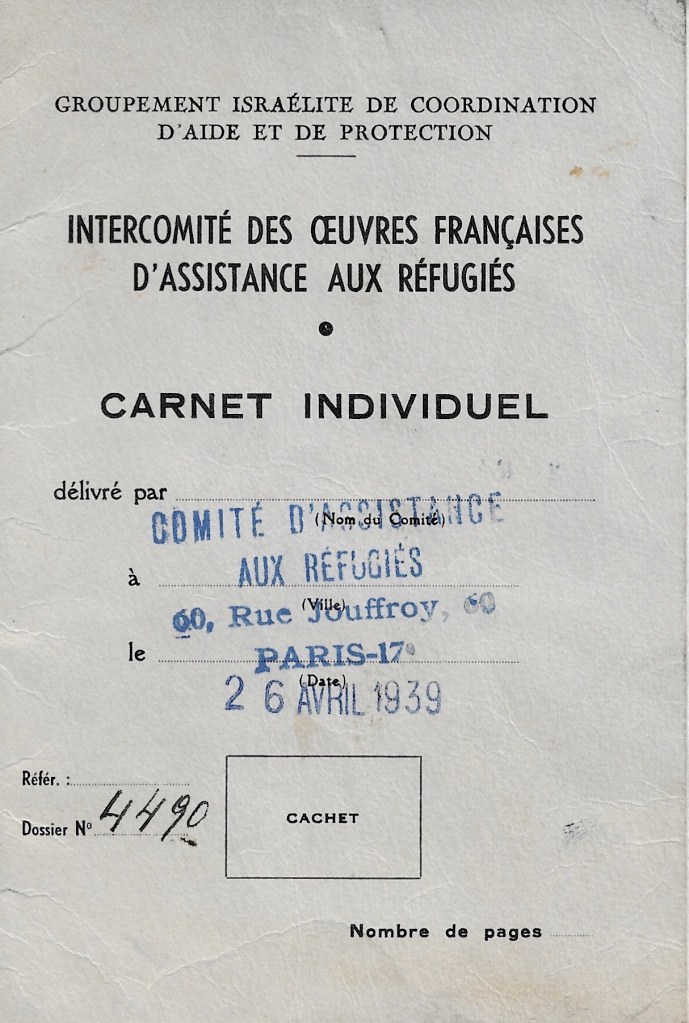

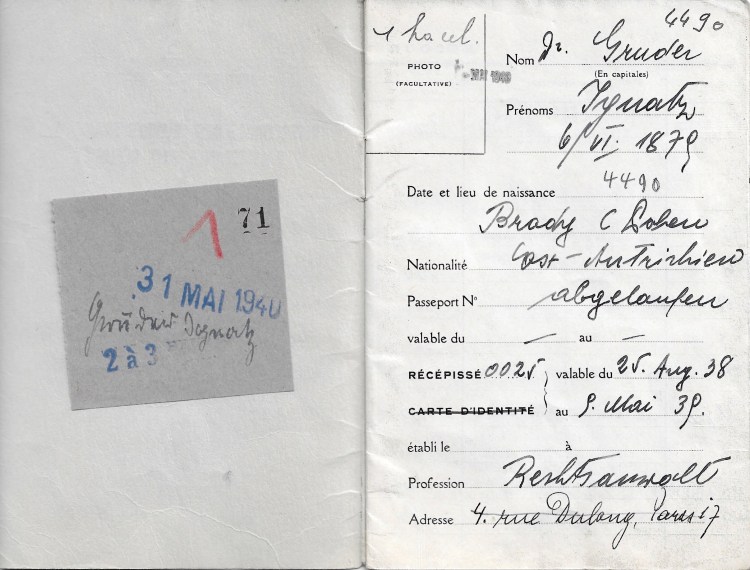

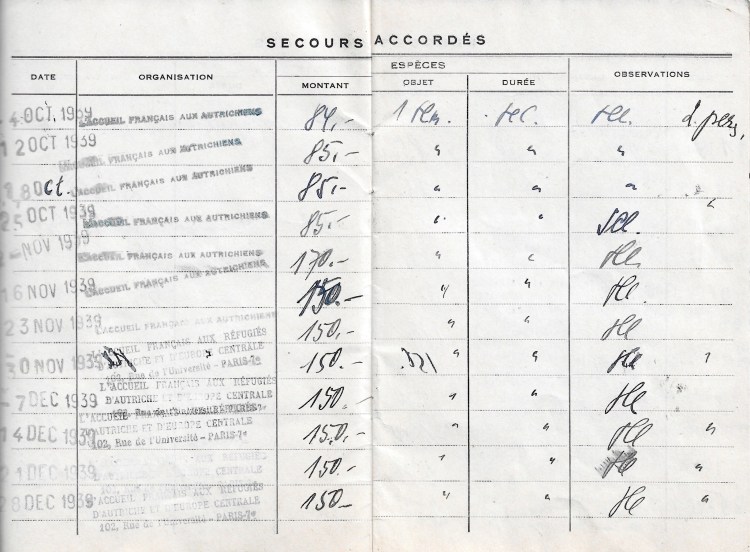

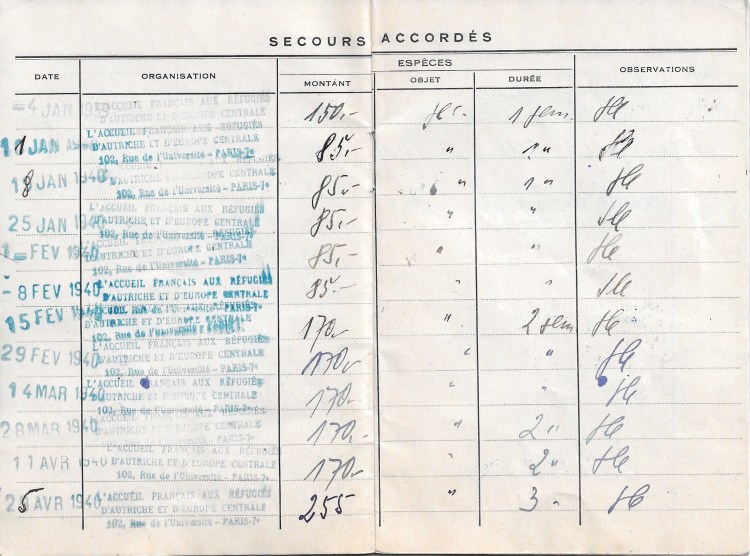

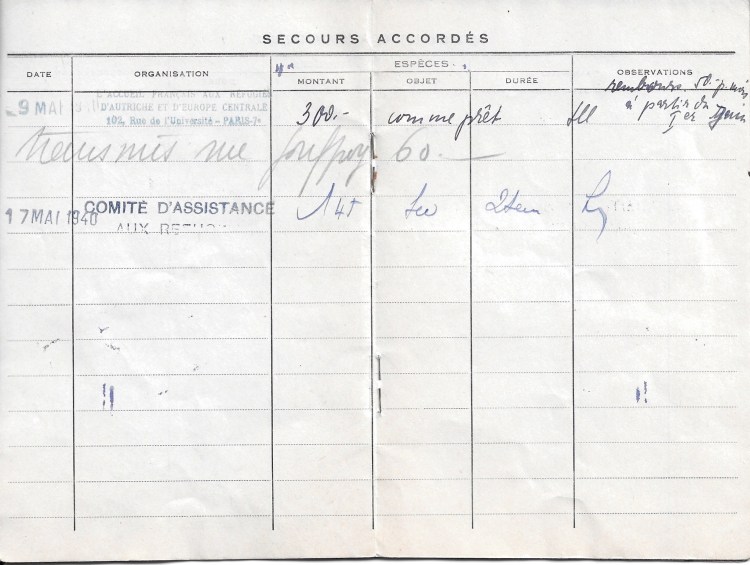

Just another series of lucky coincidences and connections made it possible to obtain a French visum and so my parents were to arrive in Paris. And I had no idea how I would be able to support them. Yes, there was a committee which had very little money, but they helped a bit.

But that wasn’t enough to live on and there again luck was in my favor. I went to a Viennese lawyer who had years ago emigrated from Vienna to Paris and was one of the lawyers of the Austrian embassy. [ed: Roberto Reich, lawyer to the Austrian legation in Paris before the annexation of Austria.] He had emigrated because he was a homosexual, and it was easier and more convenient and less frowned upon to be that in Paris than in Vienna. And, of course, he was also a socialist (nominally a socialist,) and knew my father and professed great admiration for him, and he declared himself prepared to hire me as an office helper. Well, very quickly I became his assistant because it turned out that he was extremely lazy, and I ran the office. I believe I told you this in another context, how we represented Austrian refugees and how, luckily, I once unexpectedly had success with an appeal and our practice flourished, so I won’t repeat it again.

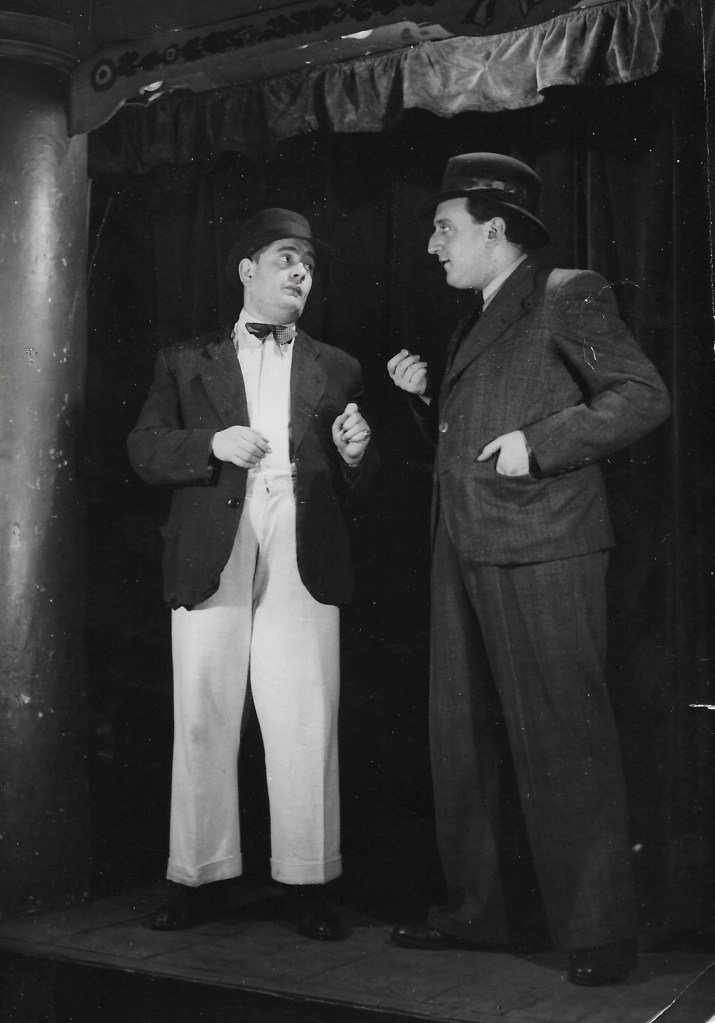

But coincidental with that employment, the arrival of my parents in Paris, the rental of a small apartment (a furnished apartment,) on the Rue des Martyrs in which the three of us lived, brought another occupation for me. There was a group of Viennese cabaret people and actors. None of them had permission to reside in Paris. They all were supposed to reside in Mélun or somewhere near Paris but of course were illegally living in Paris. One of them had been a rather prominent entertainer in Vienna, a comedian, very funny guy. Not very bright but very funny, and he had brought with him numerous sketches that he had played in something like Vienna’s Lido or the Fémina and he had the idea to band together all these unemployed refugee artists and to mount a Viennese revue show, a nightclub sort of thing, in Paris as entertainment for other refugees.

It strikes you, perhaps, as curious that one should expect refugees to be affluent enough to go to be entertained somewhere. Well, not all the refugees were poor. As a matter of fact, I met the most incredible people. I met people who engaged in activities the existence of which I had not known before. There was such a thing as a, in Viennese slang called a “Keiler”. To explain this peculiar occupation, I have to go back a bit and give you a picture of Jewry in Vienna.

There were Jews who had lived for generations in Vienna or in the German-speaking part of Austria, mostly concentrated in Vienna. And then, at the end of World War I, there was a great influx of Galician Jews, Romanian Jews, all people who fled Russia, who fled Poland, the anti-Semitism of these countries, and came to their capital (to their former capital,) to Vienna. What was peculiar about it was the reception they got from the earlier Jews. I call them “earlier Jews” because they had been living there, they were born there. And I’m ashamed to say that – no, I don’t have to be ashamed because I had no share in it – but to my regret I have to say that the born-Viennese, the Jews born in Vienna, didn’t behave very nicely to what they called, disdainfully, die Flichtlinge [refugees], alluding to the fact that the people spoke German with a strong Yiddish accent. They spoke Yiddish among each other, which the Viennese Jews didn’t speak. And they looked down at them, handing out charity grandly but certainly not treating them as equals. This seems to be a phenomenon which I later saw repeated in post-war Germany when the people in West Germany who had miraculously survived, received their East German brethren who were pushed out of that part of East Germany that had gone to Poland and who fled to West Germany – they treated them also as second-class citizens. There is no great feeling of solidarity except in misery. The haves don’t like to share with the have-nots, no matter what their religion, cultural background, or nationality.

As a consequence of the treatment they got, these Zugewanderte, these recent (more or less recent) arrivals in Vienna had to live by their wits. They did not always engage in the most admirable enterprises, and one of the occupations that they engaged in (not all of them but some of them,) was to be a “Keiler.” A “Keiler” is a person who goes armed with a list of addresses, usually obtained by a sympathetic rabbi, addresses of other Jews, affluent Jews. He goes to them and peddles something, some haberdashery, clothing material, almost anything, but he doesn’t really try to sell these things. What he is trying to do is evoke sympathy. He is selling what you call in Yiddish, rachmones. That means having pity on him. And in order to do that, they engaged in some highly imaginative tricks.

I remember the visit of a beautiful old man, white haired, who appeared at the door of our house, dressed in a ragged overcoat, in a terrible state. And he opened that overcoat to show my mother that underneath he didn’t actually wear pants. He had parts of pants, that part that looks out below the coat, fastened with string just to give the appearance that he was wearing pants, and he had nothing to wear, and he was begging for clothing. Well, my mother was in tears, and she trundled out suits of my father and myself and handed them to the man and gave him money and gave him addresses of friends of ours, and the man left. Well, to my great astonishment, about four weeks later he appeared again in the same get-up as before and this time my mother realized that he did this professionally and of course didn’t give him anything. And almost — just a few days later, I saw that man on a Friday evening getting out of a house, very well dressed, most distinguished looking. He was a highly successful “Keiler.”

Well, some of these people who, as I said, have to live by their wits, had of course also a knack to get around such things as police and police surveillance. They knew ways and means to get out, to live in Paris when they were not supposed to live there, and they applied their trade in Paris highly successfully. The French Jews had never seen anything like it. And some of these people made a fabulous income. They were in their free time good spenders. They were the clients in the cabaret we eventually opened.

I don’t wish to say they were the only ones. There were some German Jewish refugees who had come to France years earlier and were fairly affluent, and also there were some Austrian refugees who had brought out some money.

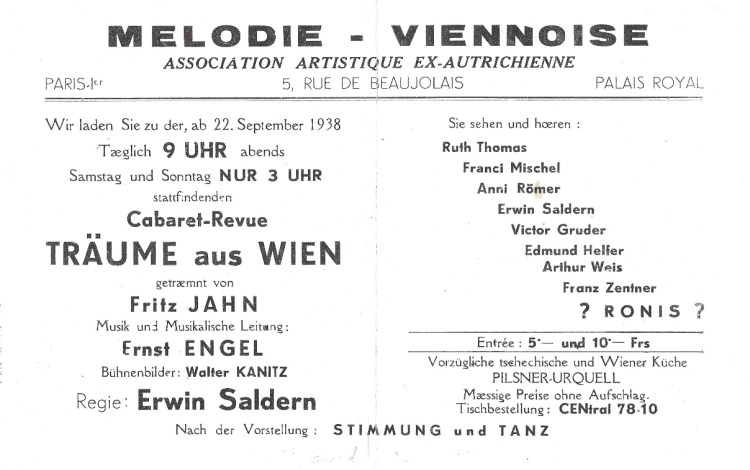

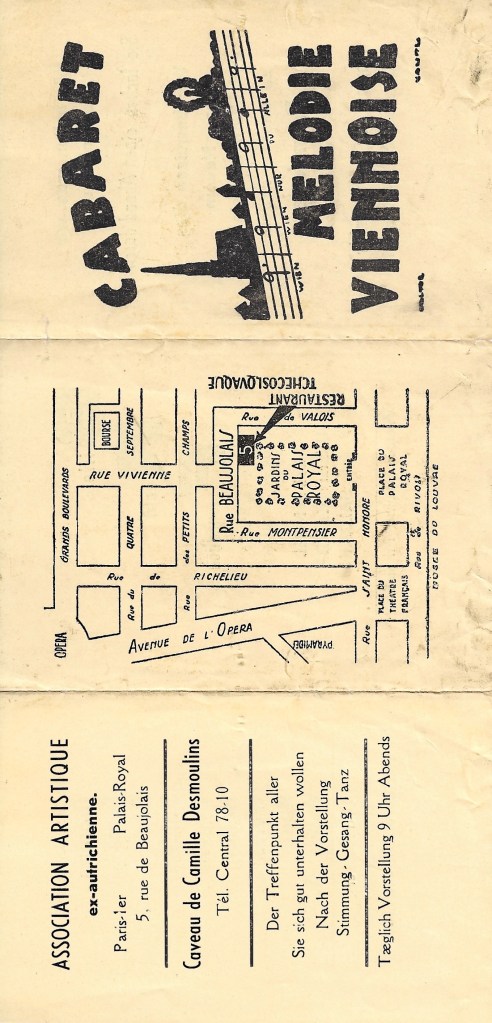

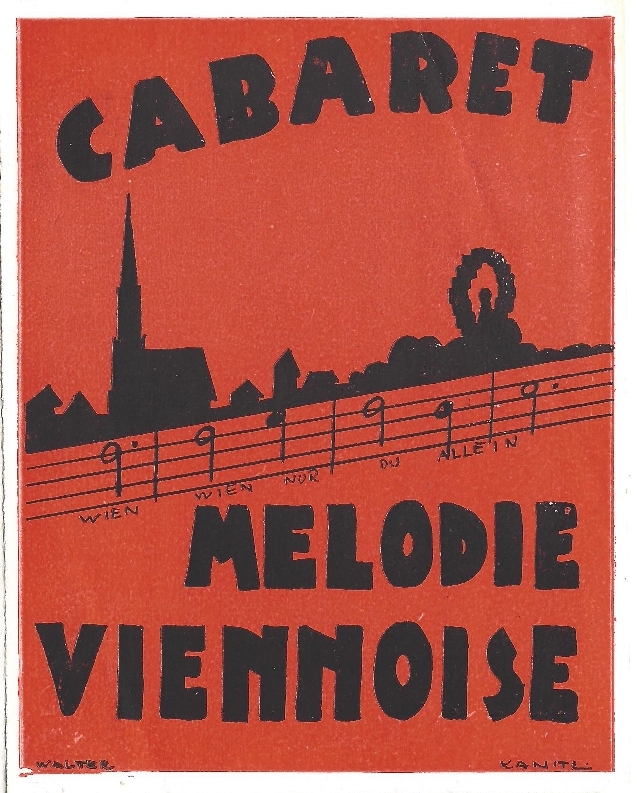

At any rate, we founded a club. I did the legal work to make that club a legal entity and in a restaurant which was run by a non-Jewish Czech, in the cellar of a cave in the Palais Royal. It’s a cave where Camille Desmoulins helped plot the French Revolution, a historical place, and it had a little room which lent itself — which had a small stage, and it lent itself for the purpose. As a matter of fact, it no longer exists today but after World War II, it was a fairly well-known cabaret called Milord.

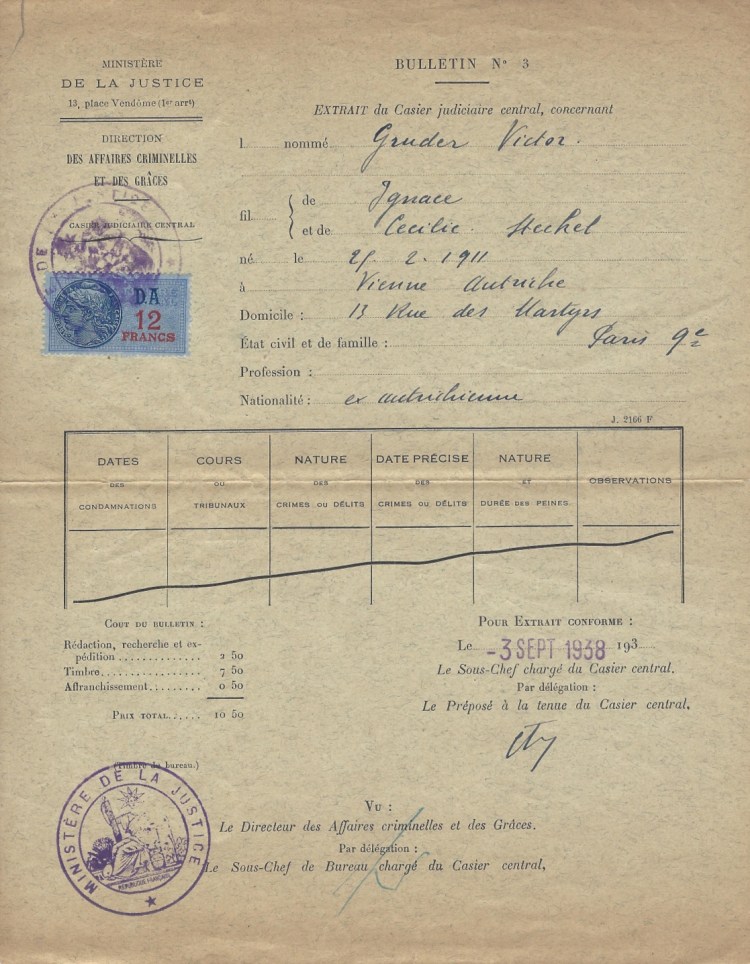

Well in our times, we called it Mélodie Viennoise and it occurred to all these actors that we are playing to an audience in Paris and there ought to be somebody who can say hello to the people in French. None of them spoke a word of French so I was not only president of that club (because I also was the only one who had the legal right to reside In Paris

and therefore was the front man,) and I became the conférencier who welcomed the people in French and introduced the show which of course was entirely in German. I not only was the conférencier; I also painted sketches, blackouts, songs were sung. Visualize this as something like the Kommödchen. [Ed: see Letter 10 “Düsseldorf” for more about the Kommödchen.] We were not quite as literary but it’s along the same lines.

And one of the complications arose because I had a hard working-day. I started in Doktor Reich’s law office at nine o’clock in the morning and finished at six or seven, and at nine o’clock I started in the cabaret, and we finished at three or four in the morning. I didn’t get much sleep at that time. I also didn’t have much time to learn my parts but, somehow, we muddled through, and I participated in this for about eight months or so.

Between my earnings at Doktor Reich and my share of the proceeds in the cabaret, I was able to support my parents and the thing ended when I left for the United States.

It was a very gay time. No, that’s not the right word. We were aware of the turmoil in Europe, we were expecting the war to break out any moment, we knew that our lives were at stake, but we somehow were dancing on this powder keg which could blow up any moment. We were young and we lived from day to day.

Dr. Reckford, whom you might remember from New York, was for a time working with us; he was our cashier. And one of our female stars was – what’s her first name? [ed: Ruth] – Suschitsky, who later became Mrs. Jungk (you know Jungk, the guy who spells his name with “gk” and is the great futurologist, well-known these days.) [ed: Ruth Suschitsky performed with Mélodie Viennoise and independently as “Ruth Thomas”.]

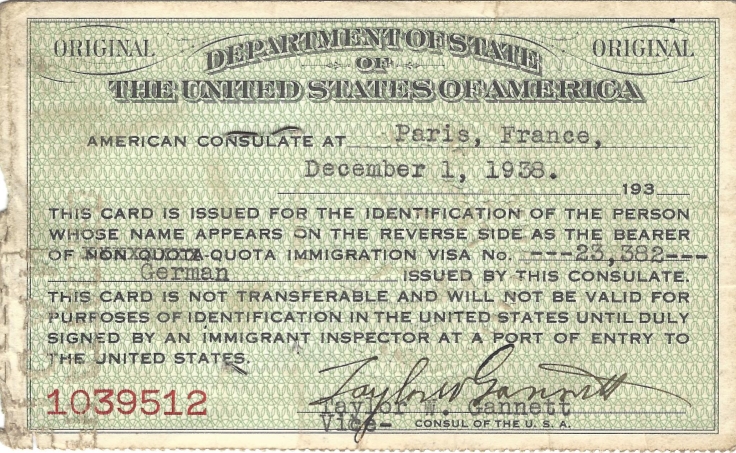

As a matter of fact, this side occupation of mine was even helpful in connection with my getting a visum for the United States. This had come about by a roundabout way. I had written to my Aunt Genia in Los Angeles that I needed an affidavit. Now affidavits are statements of an American citizen that he would assume responsibility for somebody seeking an immigration visum and that he would see to it that this person would not become a public charge. This totally meaningless statement was extremely difficult to obtain because American Jews were deadly afraid that they may actually have to shell out money. While they gave generously to organizations, perhaps because it could be written off taxes, they were very hesitant giving personal guarantees for an individual. Perhaps understandable. Anyway, we all had difficulty obtaining such affidavits although to my knowledge, there isn’t a single case in which I know of a refugee who had to invoke, or on whose behalf had to be invoked, that particular guarantee. Anyway, my aunt was not only not affluent, was also particularly stupid, and she wrote letters that, really, they don’t have any money and how can she prove that she has sufficient funds? And this went on and on. And one of the members of the U.S. consulate, one of the vice-consuls, was a frequent visitor in our cabaret. He liked one of our lady performers and he came frequently. He spoke German and in desperation, I once went to him with a letter of my aunt in which she had upon my request stated that they are running a boarding house somewhere in Los Angeles, and she wrote that on small pieces of paper; and on one of the pages she stated that this has a turnover of that much a year (a modest or sufficient sum for the purpose of an affidavit,) and on the next page she said, “But we don’t own the place. We are only renting it,” and started to decry the fact that there was little money left over for them. Well, I brought this letter to the consul and told him that my aunt is, unfortunately, not very clever, I can’t get any better statement from her than this. And that consul did something very sweet, I think. He read the letter and then he took for inclusion in the file only that part of the letter which stated how much turnover they had, and he conveniently forgot the page on which it said that they are only renting the place, not owning it. In other words, he really was helpful and eventually I got my visum.

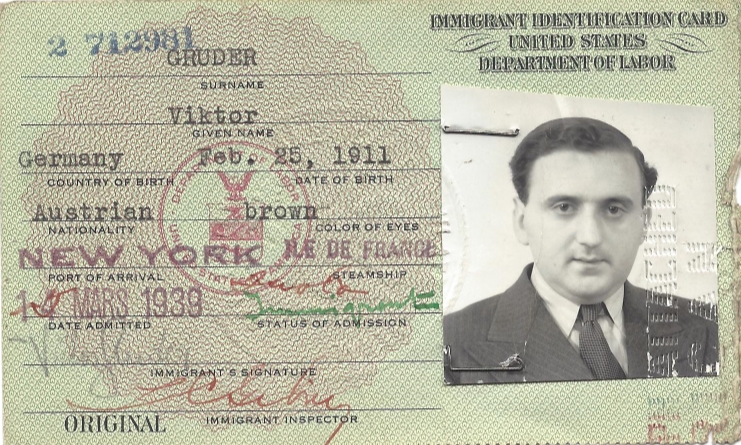

A Jewish organization of New York, the Council of Jewish Women, financed my ticket and in March 1939, I took off for the United States. I said goodbye to my parents and somehow my mother knew that she was not going to see me again. Perhaps subconsciously I knew it too.

Before leaving the subject, I’d like to tell you something about the behavior of the French at that time. You know the French have always prided themselves of being the land of the free, the land which gives refuge to political prisoners. Well, that didn’t apply to Hitler refugees. As a matter of fact, I have already told you what happened to my father but that came later. But at the time when I was still in Paris, people who didn’t know how to evade the police got expulsion orders and when they were caught again, they had to be convicted, all this under decrees which were passed as exceptional measures by the Baladier government. It was not very kind behavior but, nevertheless, they were also, the police was pragmatic about it. For instance, I learned later that they knew all about our cabaret. We had of course no license, no right to do this. They knew damn well that the people who performed there had no work permit, didn’t even have a permit to live in Paris, but the police closed their eyes to it because they were people earning an honest living, small but honest living, and they closed their eyes. That, too, existed, side by side with the rather shameful behavior of the government.

I find it interesting that this particular experience came back to my mind, very recently by a rather extraordinary experience. About one and a half years ago today, I once bought tickets at the Théâtre de la Ville, the Châtelet, and as I purchased the tickets and turned away from the box office, I sort of had the idea I know that face of that cashier, of that woman selling the tickets. And after having stepped away, I turned around and looked at her, sort of inclining my head, you know, as you search for memory, and I noticed her looking at me in exactly the same way. I went back and I asked her, “Don’t we know each other?” “Yes indeed, Sergeant Gruder,” she said in French, and it turned out that she was a girl who had worked in the office of the, during the war when I was a sergeant in the General Purchasing Office. She was then a very pretty girl (and as a matter of fact she is still a very good-looking woman today,) we started talking about the times past, and she asked me whether I remembered the other colleagues from the office. Then she asked me, “Do you remember Monsieur Vergnaud?” I said, “Yes, yes. He is that tall Frenchman who then worked for the Minister of Finance. What became of him?” She said, “Well, he made a nice career, he is working for Air Inter, and why don’t you call him?” and she gave me his telephone number. I called; I discovered that he was not just having a good career, that he was the President of France’s Air Inter, after a career in the Quai d’Orsay. He is very active politically and eventually I spoke to his wife, and we got together. He turned out to be a charming gentleman, and one day Mommy and I had dinner with him, and he told me to my great surprise that he remembers well what I told him about the failure of the French government to behave decently to refugees, how I had opened his eyes to what apparently had been a myth he had believed in. And mind you he remembered that conversation for thirty-five years. It really must have impressed him at the time.

Perhaps there is some symbolism in the fact that I left Paris with a terribly swollen jaw. Twenty-four hours before I was supposed to take the ship, the Isle de France, I developed an impacted tooth and, with great pain and a jaw about three times its normal size, I boarded the ship and discovered Anacin for the first time, on which I lived for the seven days it took to cross at the time.

And I arrived in New York. I had a recommendation from an American rabbi [ed: Rabbi Goldberg, a remarkable individual who later married Jeanette and Victor] who had been helpful in connection with obtaining a visum and he had given me an address where — in his parish in Astoria — where I could rent a room, and this is the place to which I proceeded, and this is where my life in the United States began. My total fortune consisted of one suitcase, plus a suit I wore, and five dollars and a bag full of preconceived notions about America in general and about New York.

I discovered very quickly that all my preconceived notions — but all of them — were entirely wrong, both positively and negatively. Nothing was as I had expected it. There I was in the land of the free, and the land of plenty, and we in Europe had never realized what the Depression meant in the United States. I was simply not prepared to see that much misery around me, that much dirt, that much ugliness. And I assure you, New York was ugly at the time, particularly where you arrived with the ship. The piers were dirty, unkempt, and it’s the ugliest sight of New York, even today. That was the first disappointment. No, not disappointment — wrong preconceived notion, idée reçue, all wrong. I saw the then-elevated subway on Third Avenue, on Sixth Avenue, ugly as hell, noisy, dirty; the fire escapes on the outside of the houses; I was totally unprepared for the brownstones.

But then of course there was also the reverse side. I was totally unprepared for the kindness, hospitality shown by complete strangers, by the rare shopkeepers, people in the congregation of Rabbi Goldberg. It included the dentist who took care of my horrible tooth and he, of course, didn’t charge for it. As a matter of fact, he showed me New York and I beheld for the first time, Fifth Avenue. I remember that he insisted on showing me St. Patrick’s Cathedral (which to somebody coming from Cathedral France, is not terribly impressive, and I kept on craning my neck looking in the opposite direction at that incredibly beautiful Rockefeller Center, which I consider one of the great monuments of the 20th century.) For some reason, New Yorkers insist on taking you to Grant’s tomb. Never understood then why, I don’t understand it today — nothing to see, nothing memorable about the monument or about Grant, for that matter. But it needs to be seen and it was only much later that I discovered the Cloisters which are marvelous.

But the outward appearances were not the important thing. What was important was the fact that you were accepted.

In the middle of a Depression, there was an organization, that famous Council of Jewish Women, which was established on Times Square in a huge office, and one reported there, and they had a professional staff helping people with money, with jobs. Not choice jobs, but jobs anyhow. They gave you addresses to apply for work. I make it sound as if that had been easy. It wasn’t. It was very difficult to land a job and that Council, incidentally, had an excellent policy. They wanted to know from you, in detail, who your — what relatives you had in the States — and they went after these relatives with a vengeance for contributions, for money. But when you had nobody, they helped you out.

I presume this is how I managed. I had a few friends from Vienna, who were just as badly off as I was but, somehow, we survived, and we made our frequent visits to the Council to look for work. And it was on one of these occasions that something happened which is fateful for your existence but in order to tell you that, I better go back a bit in time.

I told you that in Paris when we first arrived, Kalmus and I, we lived in the Hôtel de la Havane. I also mentioned that there were a whole group of men there. We passed our evenings usually playing cards in the lobby and one of the men there who took me aside (we were also pals,) he wants to discuss something very serious with me. He related that there was a girl in Vienna with whom he had been going for many years and who expected him to not only bring her out of Austria but to marry her. Now he was in a quandary because he really was in love with a very pretty girl who incidentally was arriving the next day (she was on the way to the United States,) and she would stay in the hotel for a night, and what should he do? He is much more in love with the pretty girl than the one in Vienna. What should he do? Well, I ventured the obvious opinion that the most important thing was to get that girl out of Austria. It was not so important whether he married her but first of all, you’ve got to get her out. And that was that.

Well, the next day there arrived indeed a very pretty girl who was introduced around and we all looked at her with envious eyes because she was the only one who had a visum to the United States. We were quite impressed by that fact. The next day, she left for the United States, and he stayed behind in Paris.