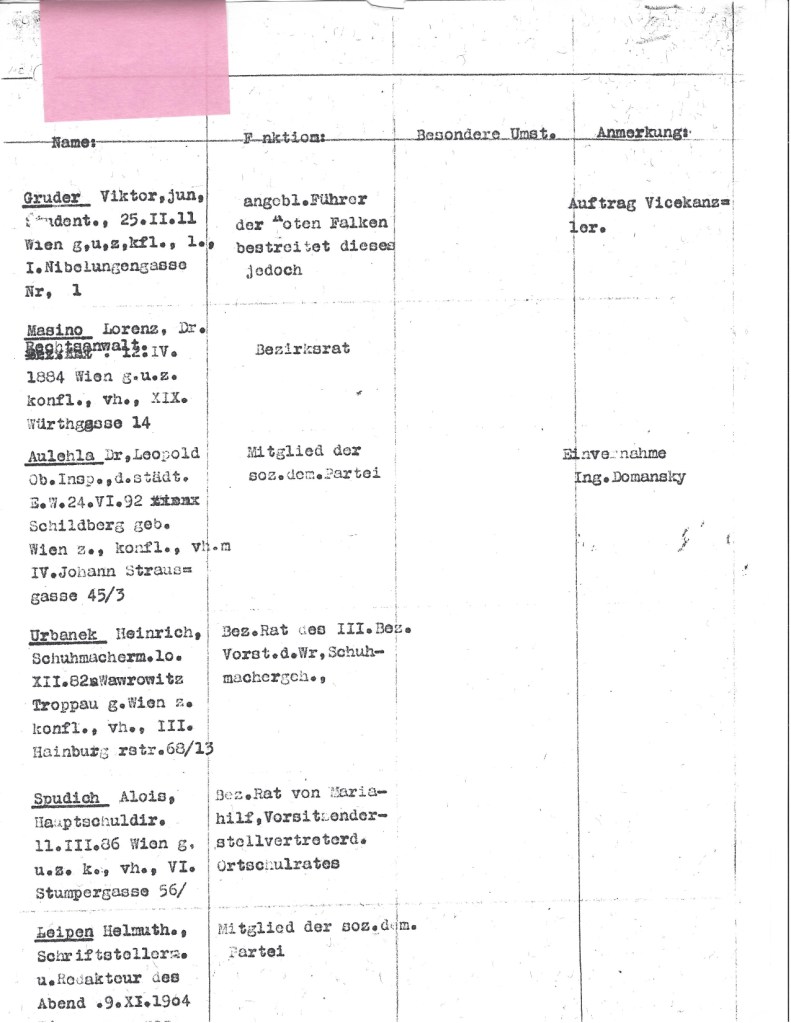

On Feb. 15, 1934, (the day after the Feb. 12-14 February socialist “Schutzbund” uprising was quelled) [ed: see Austrian Civil War], Viktor and his friend Heinz Gollmann arrived at the Gruder apartment late one evening, planning to have Heinz sleep there as he had many times in the past. There they found the police searching the apartment and questioning Ignaz. Viktor and Heinz were immediately swept up into the inquiry and all three were taken to the police station. While Heinz was released, Ignaz and Viktor were jailed simultaneously but separately, both without having been arrested or charged with anything.

The term “arrest” is not mentioned; no charges are specified. They spent 4 weeks in jail and then were released, 2 hours apart, without explanation or charges ever having been laid.

Subsequent to this episode Ignaz, who was diabetic and whose health suffered greatly in jail, lost most of his hearing and struggled to maintain his practice as business dropped away. Cicilia began to rent out rooms in their flat to provide some income, and Viktor sought to diversity his skills and generate an income.

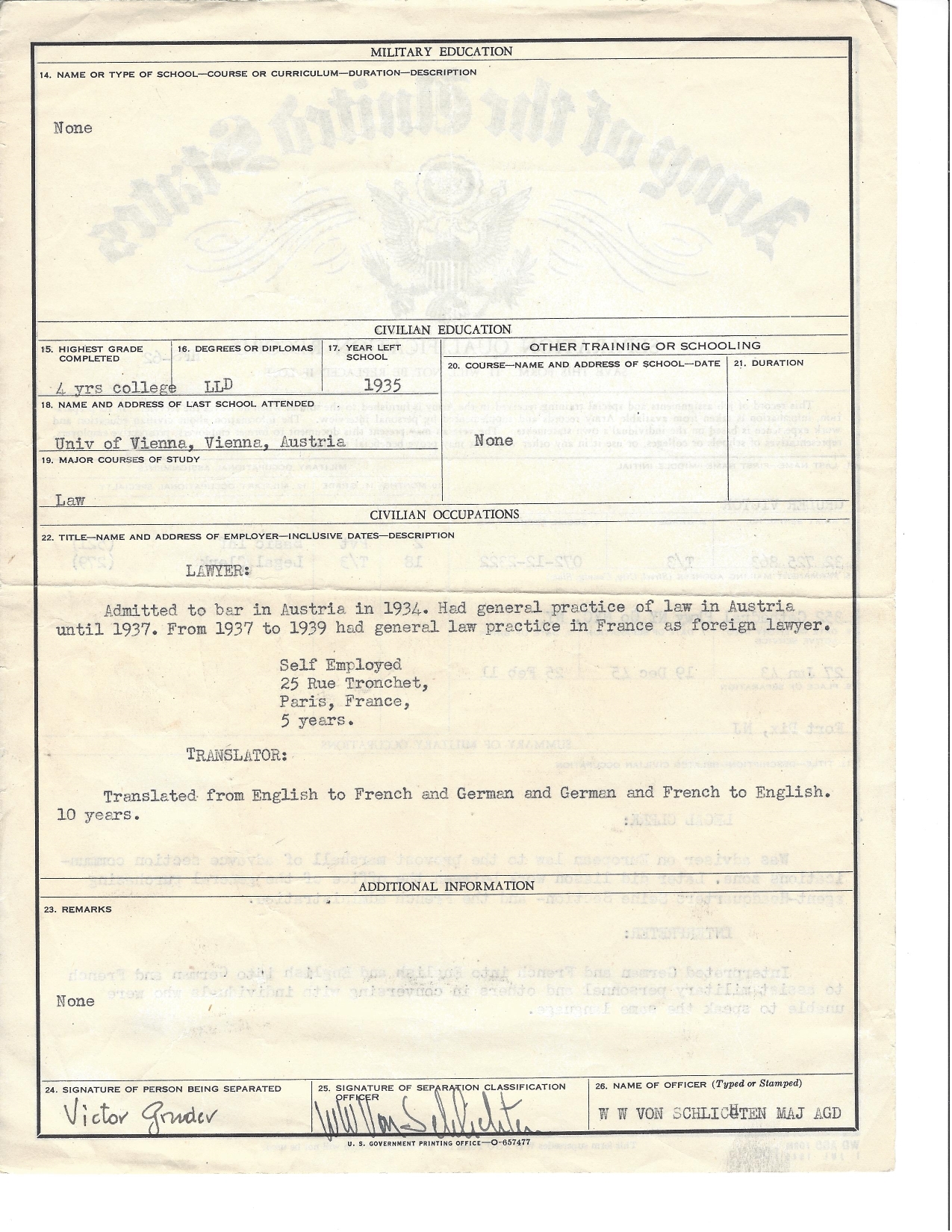

He was admitted to the practice of law on May 19, 1934, but the legal work available to him in his father’s practice was insufficient to support him or for him to contribute in any significant way to the family’s needs. From that point until he left Vienna definitively in 1938, Viktor worked with his father as needed but also worked outside the law office and the legal profession.

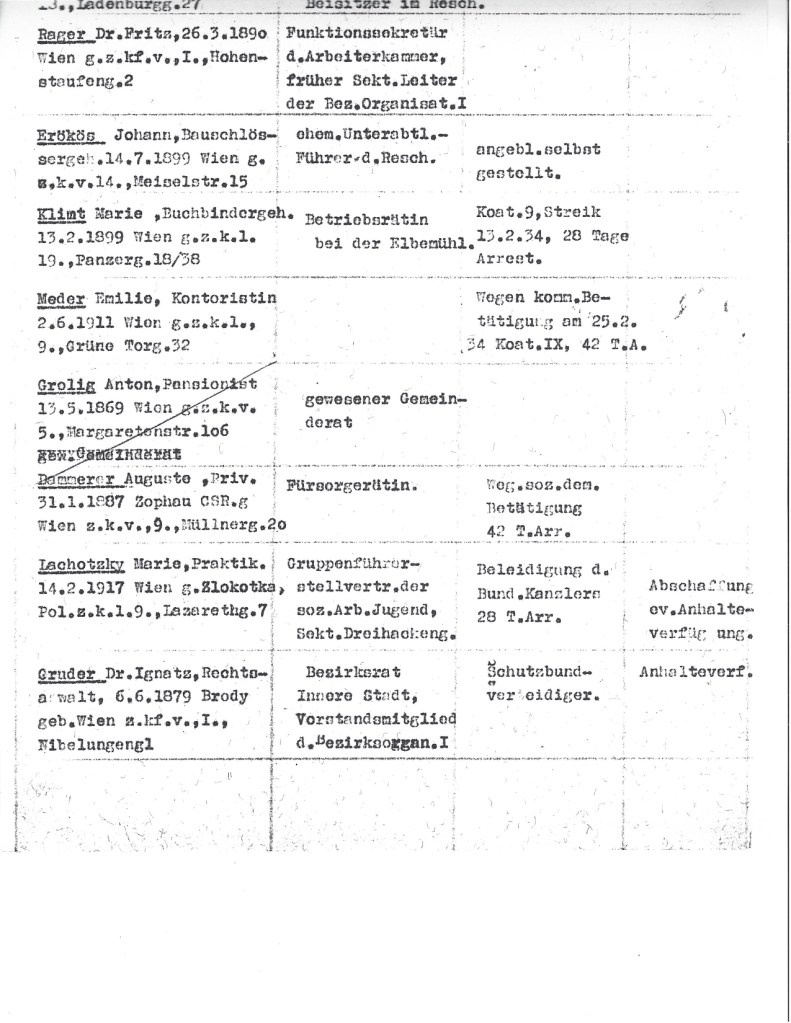

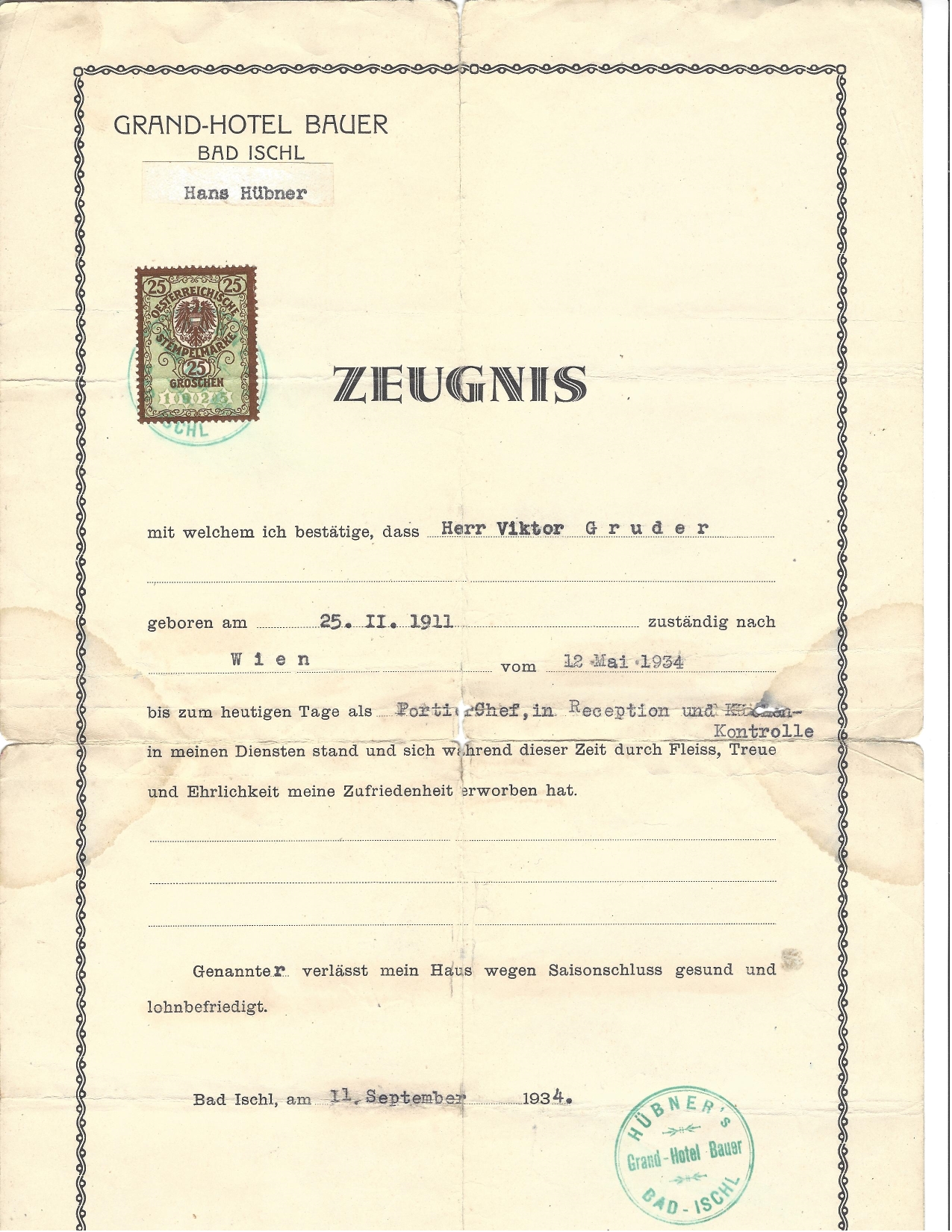

He attended the Kofranek cooking school in Vienna from March 1 to May 30, 1934. He was head porter and ran reception at the Grand-Hotel Bauer in Bad Ischl during the resort season from May 12 to September 11, 1934.

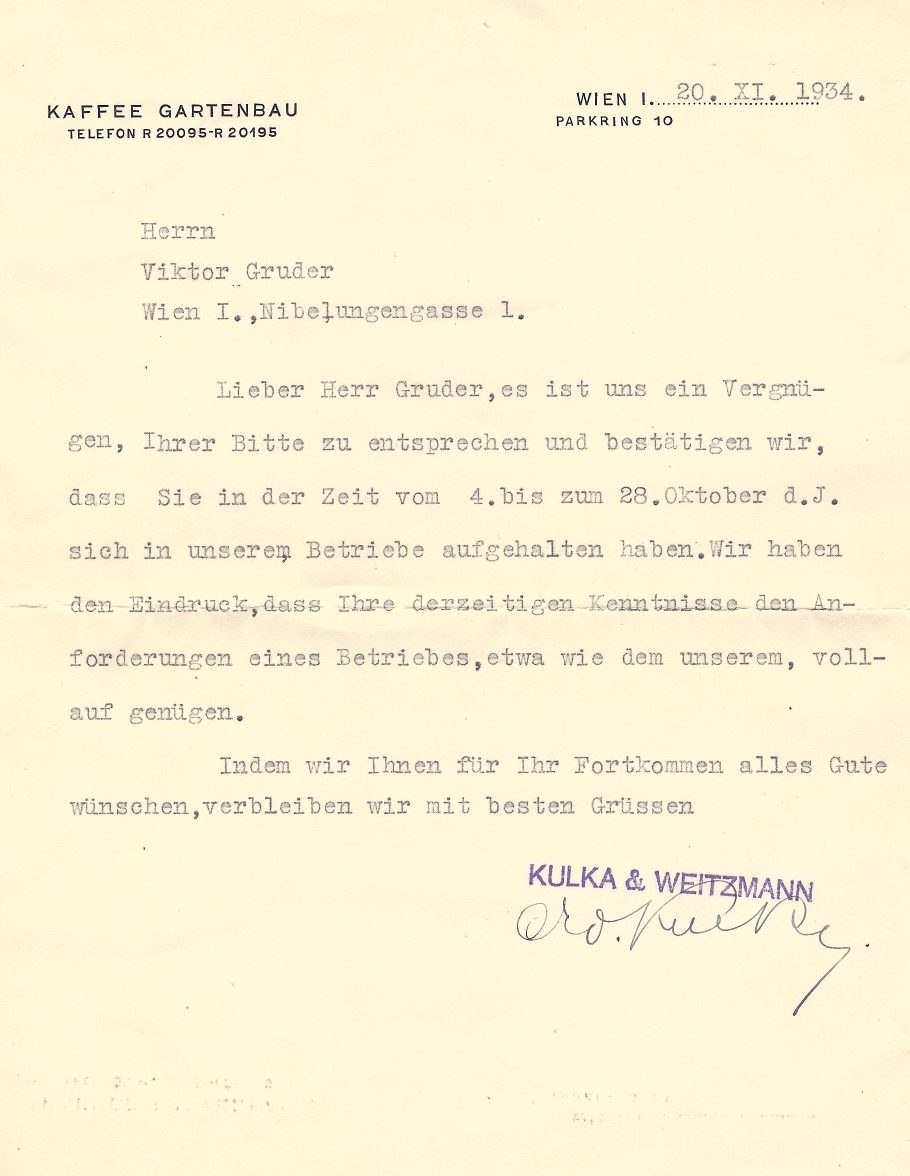

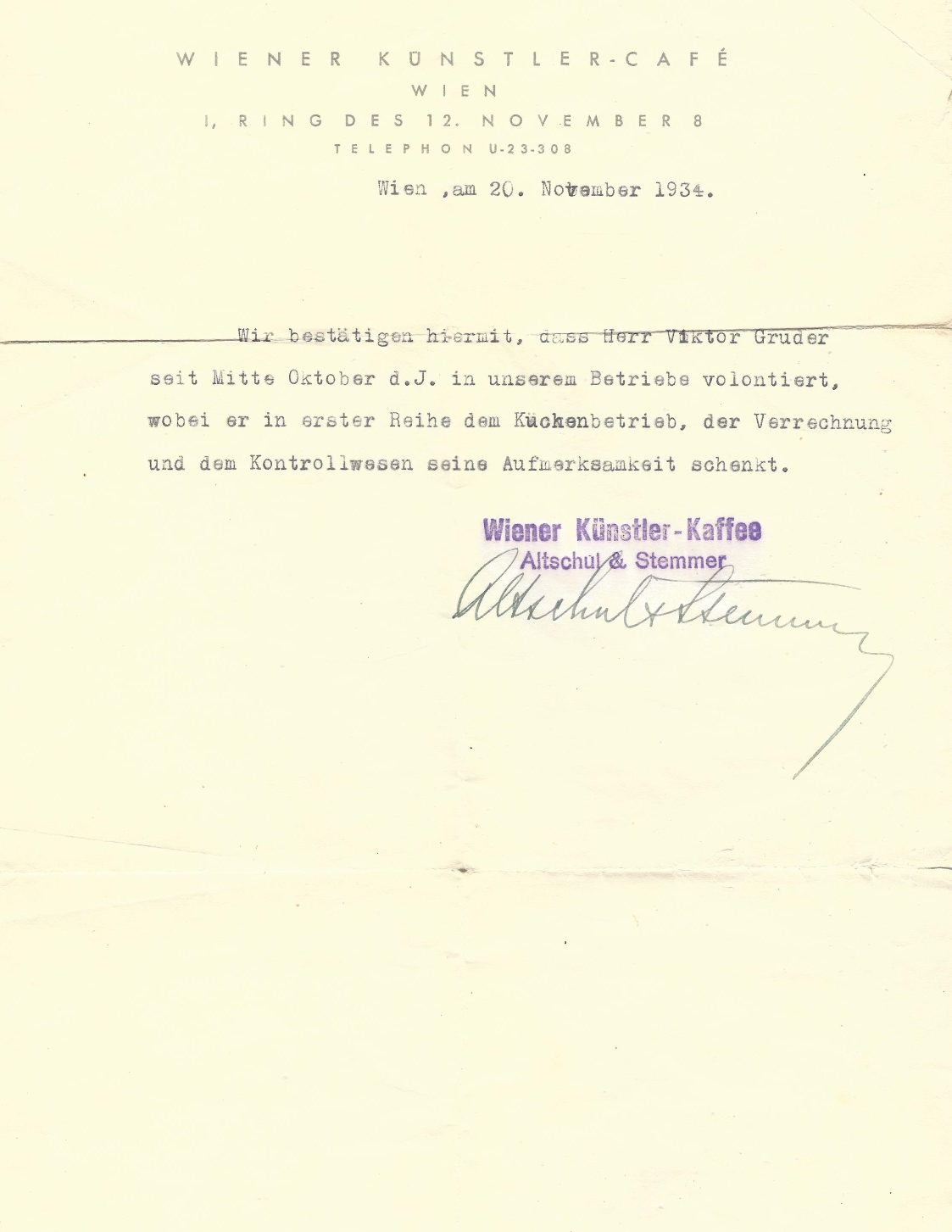

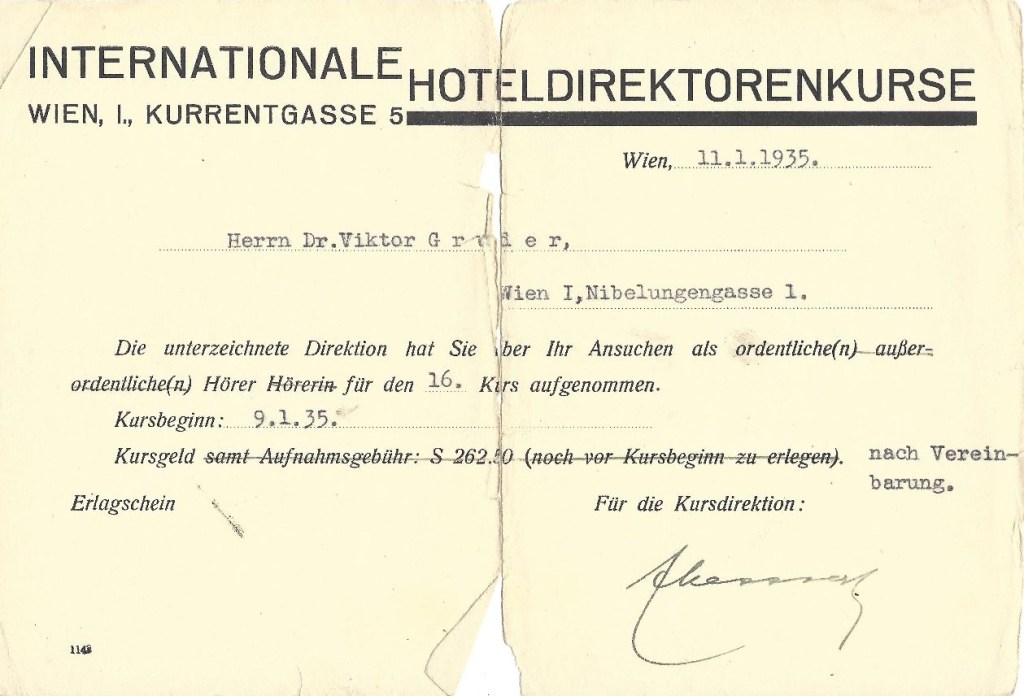

Back in Vienna, he waited on tables at the Kaffee Gartenbrau and at the Wiener Künstler-Café in October 1934, and then shifted to porter and reception duties at the Hotel Imperial, Vienna from December 1 1934 to March 10, 1935.

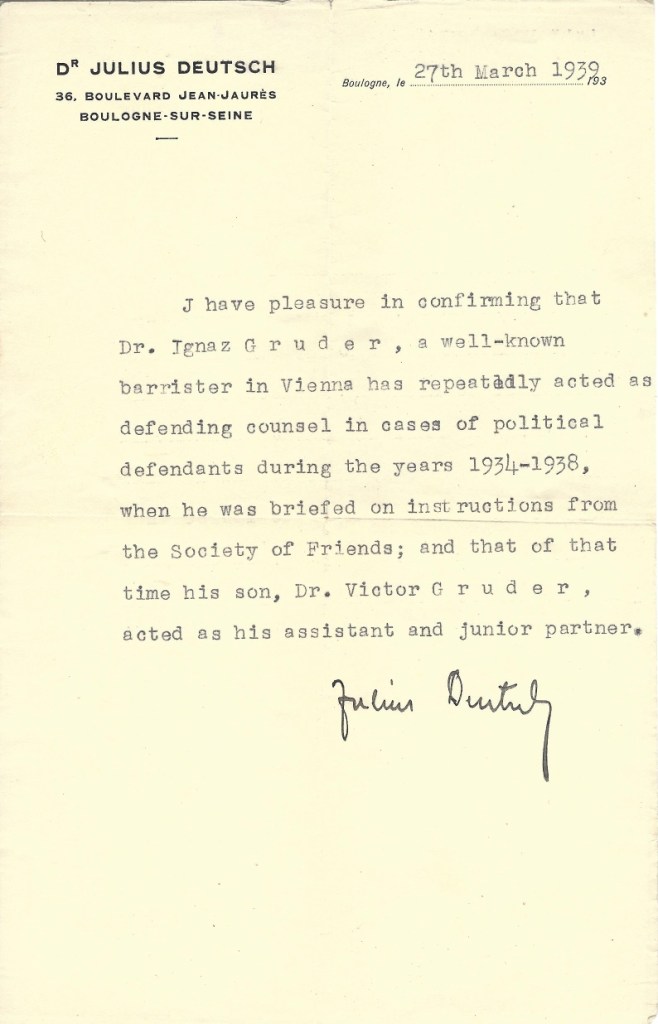

4 April 1935 was the beginning of the Schutzbund Trial in Vienna, a trial of many weeks in which Ignaz participated as one of the defense counsel (along with Drs. Richard Pressburger, Oswald Richter, Heinrich Steinitz, and others.) [ed: see “Austria From Habsburg to Hitler”, vol. 2, Charles A. Gulick, University of California Press, 1980, p. 1329.] Viktor assisted his father in this trial but perhaps only in its preparation. He also assisted him in preparation for the trial of Revolutionary Socialists, 16 March to 24 March,1936 (the year following the Schutzbund Trial). During this trial, Bruno Kreisky (amongst many others) was convicted of high treason for which he served 21 months in prison. See Kreisky’s autobiography, “The Struggle for a Democratic Austria Bruno Kreisky on Peace and Social Justice”, eds. Matthew Paul Berg, Jill Lewis, Oliver Rathkolb; Bergahn Books, 2000, pp. 135-145. But Kreisky’s sentence was for only 18 months, which is a laughable sentence for high treason. Others were given the same sentence or less. This is presumably why Victor refers in his Letters to the result as an “acquittal”, which it was not.

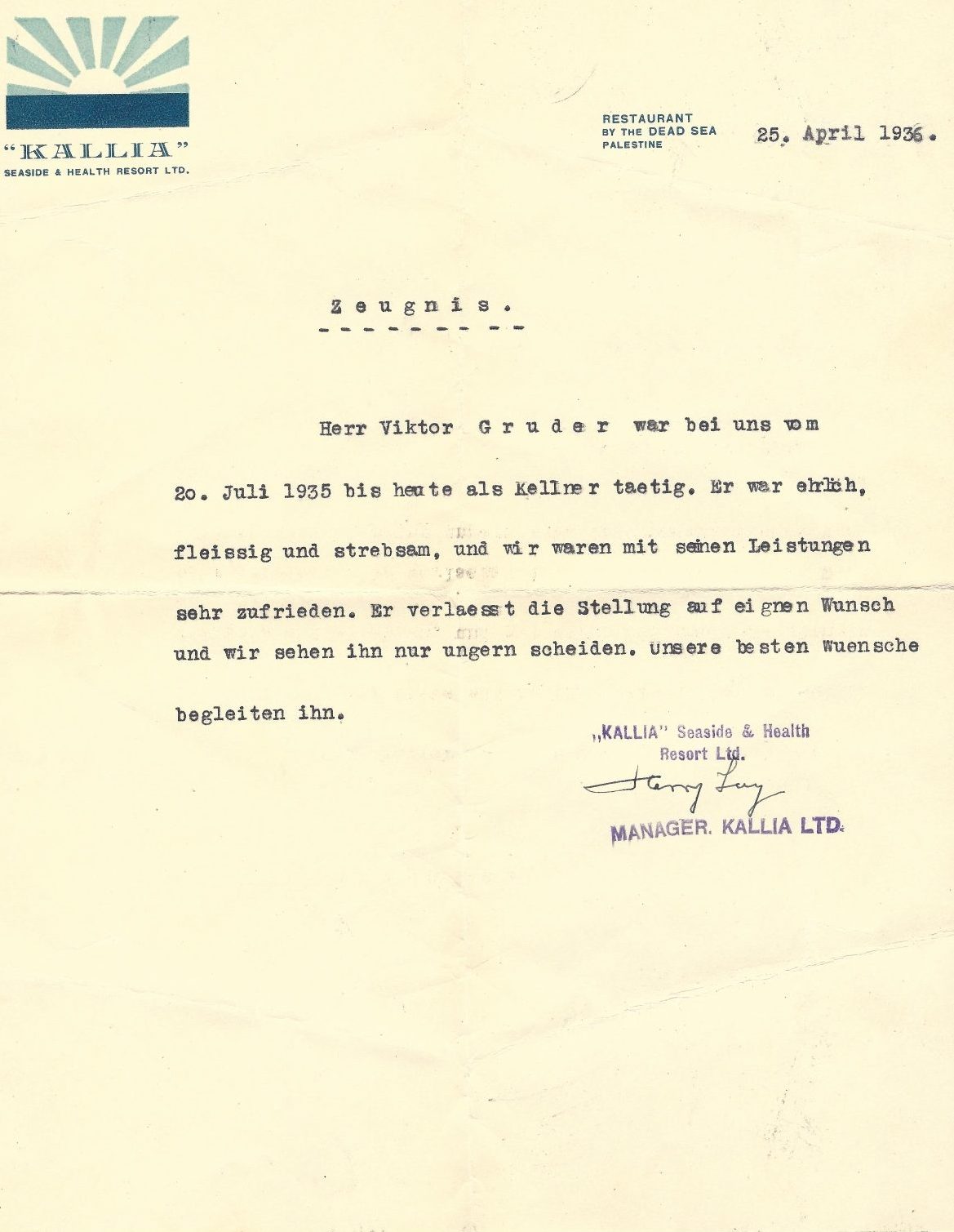

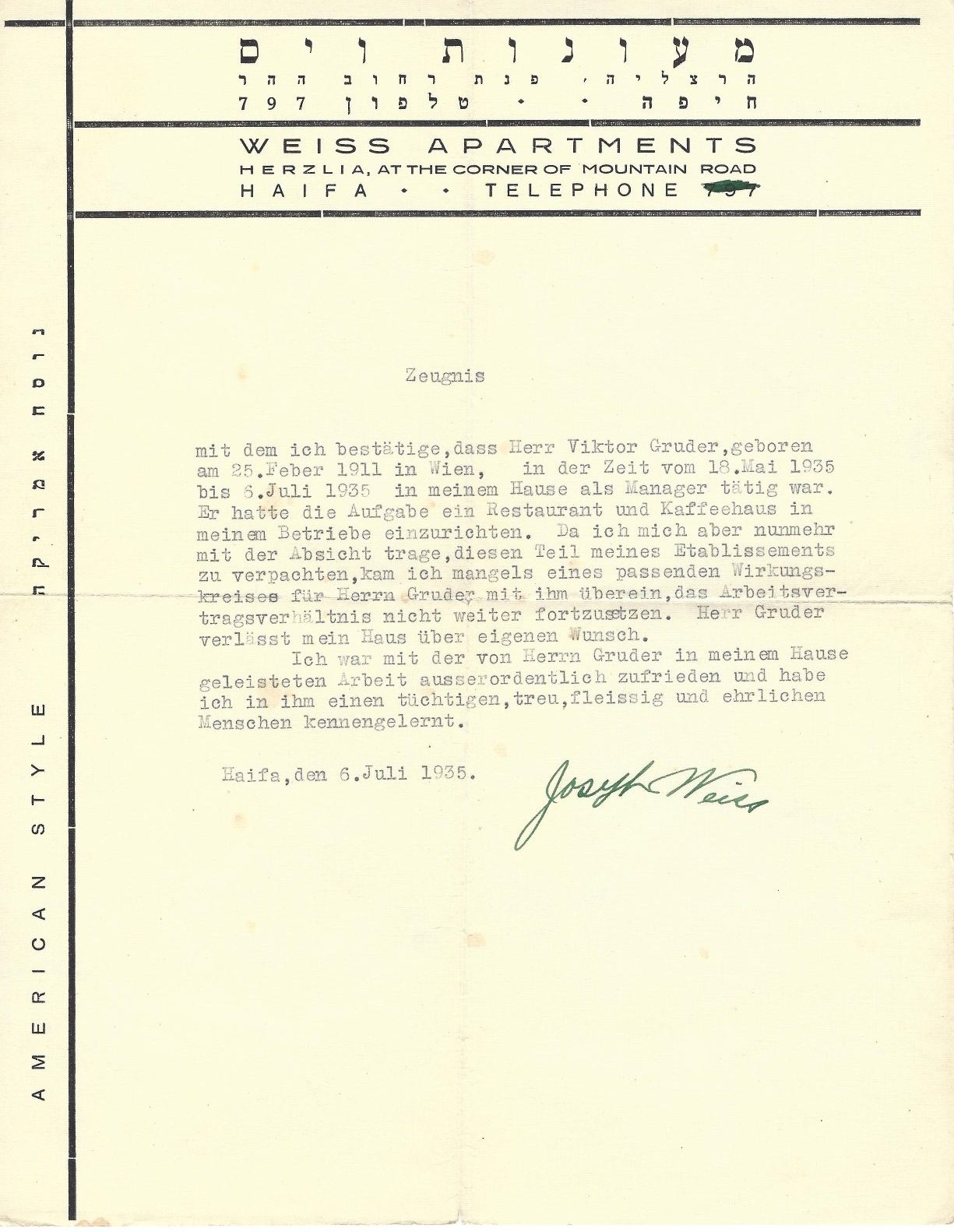

In 1935, Viktor had been issued a British visa for travel to Palestine on 18 March 1935, which was later extended through 7 October 1935. The Suez Canal Police stamped him into Port Said on 2 August 1935, and then the Palestine authorities stamped him as exiting the territory at the Haifa Port on 28 August 1935. By his own account, he was first the manager of the Weiss Apartments in Haifa (from May 18 to July 6 1935); and then a waiter at the Kallia Restaurant by the Dead Sea, from July 20 1935 onward.

It is confusing to reconstruct what happened during this period. While Viktor remembered this trip to Palestine and his later one to Egypt as two parts of the same voyage, and the above reference letter from the Kallia describes him as working there from 20 July 1935 until the “present day” (25 April 1936,) his passport indicates that this cannot be true. Viktor exited Palestine on 28 August 1935, was stamped through Italy on 3 September 1935, and returned to Vienna where he took a hotel management course for several months.

During this time in Vienna, Viktor apparently secured another visa for Palestine, this time along with an immigration certificate, on 16 January 1936, good for a single journey before 30 June 1936. On 22 June 1936 he received an Austrian exit permit, allowing him unlimited travel, and on 24 June 1936 he obtained a visa for Egypt good for 12 months which he needed to carry out a courier trip to Cairo. On 25 June 1936 he was stamped out of Austria, on 27 June 1936 he exited Italy, and on on 2 July 1936 Alexandria city police recorded Viktor’s arrival in Alexandria. He was accompanying a coffin being repatriated from Vienna, returning it to the deceased’s home in Cairo. The same police control in Alexandria noted his departure on 14 July 1936, and he re-entered Italy on 19 July 1936, not having exercised the permit he had obtained to immigrate to Palestine.

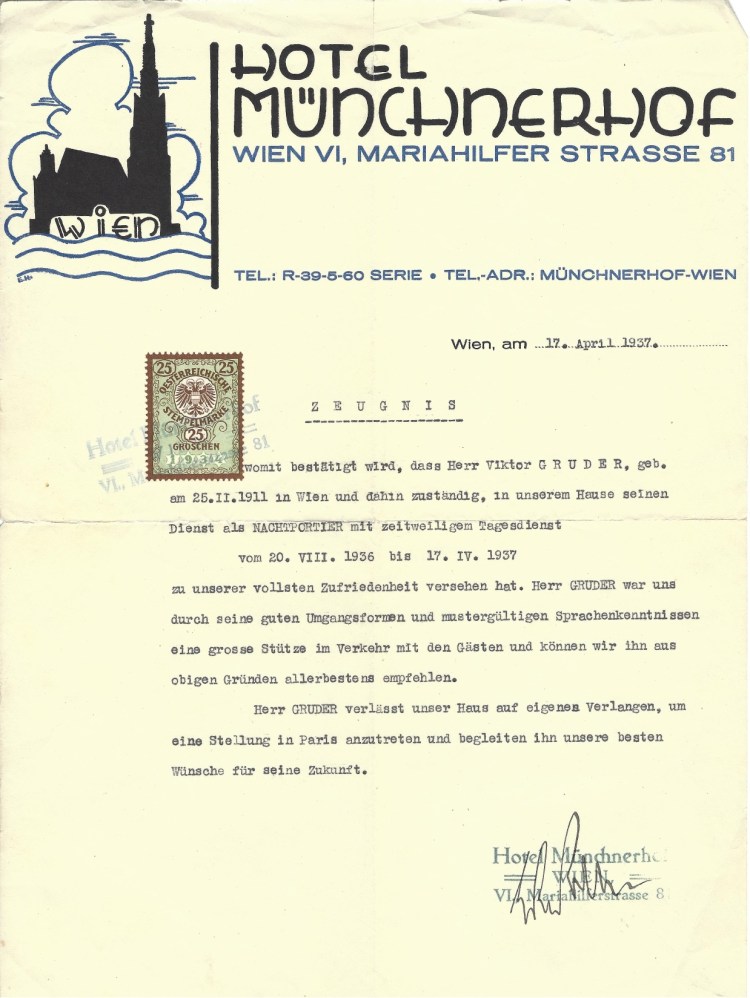

Upon his return from Cairo, Viktor had to find work and he returned to hotel jobs.

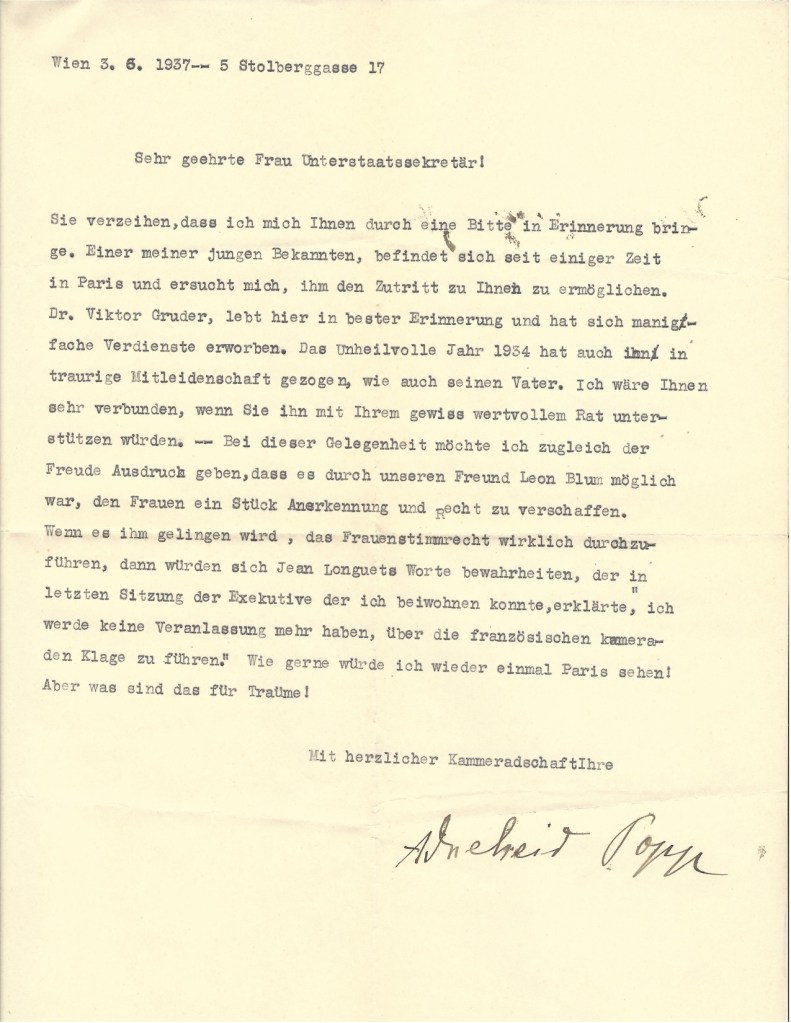

He resumed work as a nachtportier (night porter) at the Hotel Münchnerhof in Vienna from August 20 1936 until April 17 1937, at which time he again left Austria in the hope of finding employment in Paris. Viktor was fluent in French, knew the city very well from many trips there with his family, and hoped to find better work there than at home.

Although armed with letters of reference, he found the unemployment situation in Paris – even during the 1937 World’s Fair – worse than in Vienna. He did informal tour guide work for Viennese friends running a shoestring travel agency, taking visitors around the sights, cabarets, and museums of Paris. The World’s Fair, however, came to an end and so did Viktor’s work. He returned again to Vienna.

Back home in early 1938, Viktor and some of his friends came to the decision they needed to leave. Musical soirees would not save their lives, let alone provide a living. There were no opportunities for them, and the Nazis were about to assume power.

Viktor and his friends, Otto Neumann and Ludwig (“Viggi”) Kalmus, headed first to Italy. Otto stayed in Milan with his uncle. Viktor and Viggi went on to Berne, where the French Consul was willing to issue them visas.

Viktor proceeded to Paris on 18 March 1938 and worked at anything he could find. While he was a political refugee and legally a resident of Paris, work was again as hard to find as in Vienna. Viggi was better situated; he was a philatelist and collector and was able to get some work with stamp dealers.

On 31 March 1938, just days after Viktor left Vienna, Ignaz was again jailed – this time with his Schutzbund colleagues Steinitz and Richter. [ed: see Jewish Telegraphic Agency archives from 31 March 1938]. Ignaz was, miraculously, released when he was recognized by a former legal acquaintance. Steinitz and Richter both went on to work camps and eventually concentration camps where they were both murdered, Steinitz at Auchwitz (see above hyperlink) and Richter at Buchenwald.

Together with a group of Viennese cabaret entertainers living illegally in Paris, Viktor set up a Viennese revue show at 5, rue de Beaujolais. As the only person who had a visa and spoke French, he became the public face of the cabaret, called “Mélodie Viennoise,” as well as the host.

Ignaz and Cicilia were able to obtain visas for France and fled to Paris in May 1938. Viktor, desperate upon hearing that they would be dependent on him for a place to stay and means of support, contacted a Viennese attorney established in Paris and asked him for advice. This attorney, Roberto Reich, had admired Ignaz in earlier days, and he hired Viktor on the spot as an assistant. In this way, Viktor supported his parents during the day, maintained the cabaret in the evenings, and got very little sleep.

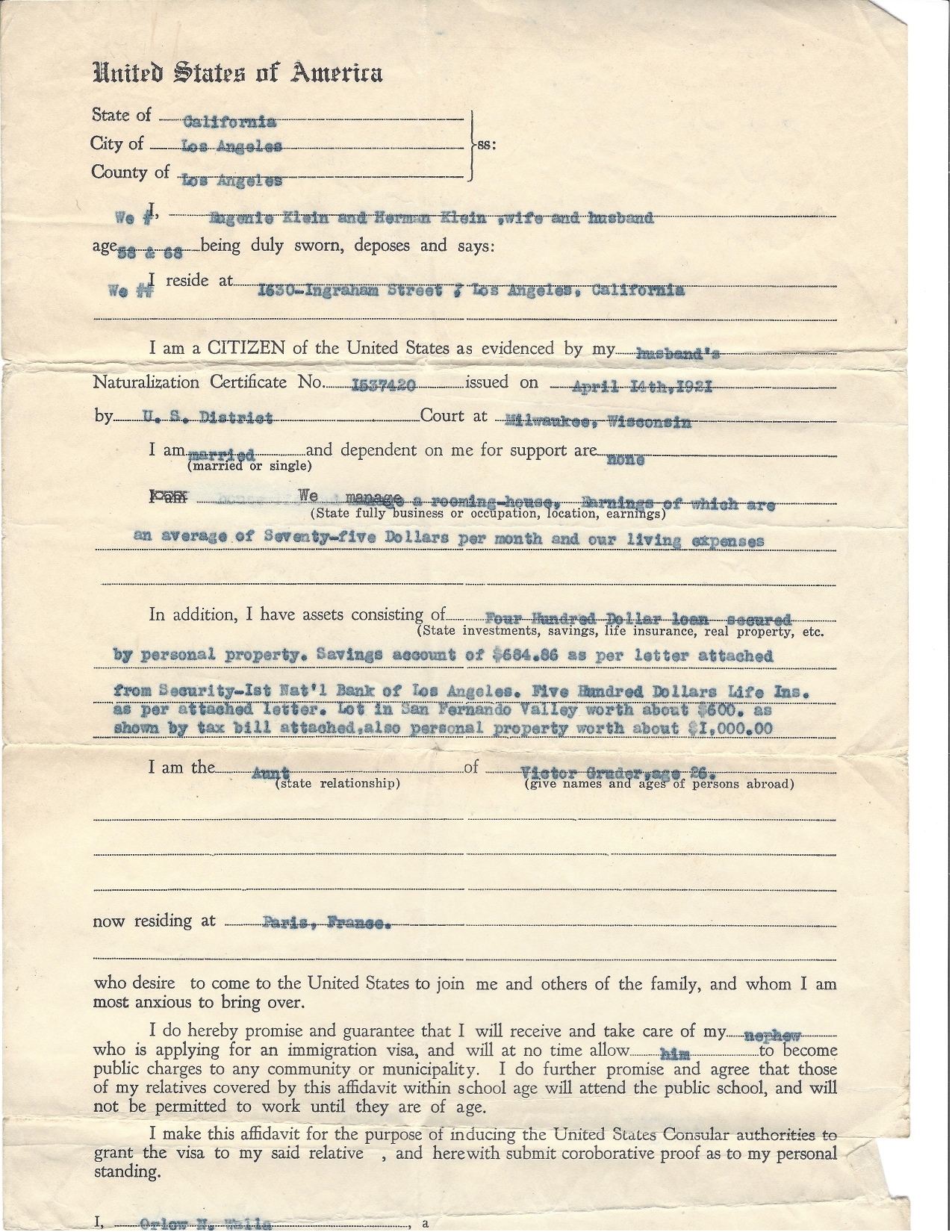

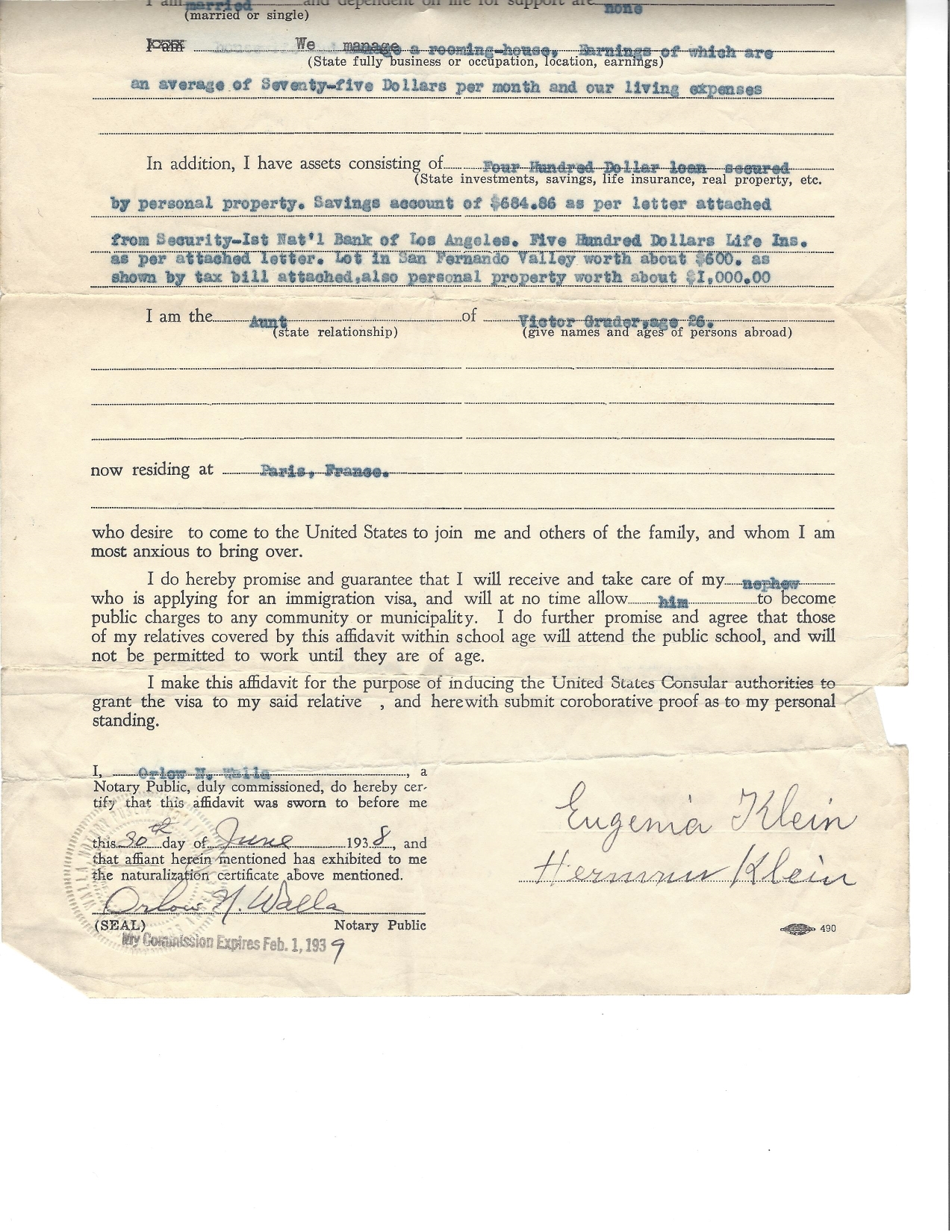

Viktor recognized that he had no future in Paris and applied for a visa to proceed to the U.S. His maternal aunt Genia in Los Angeles supplied the required affidavit.

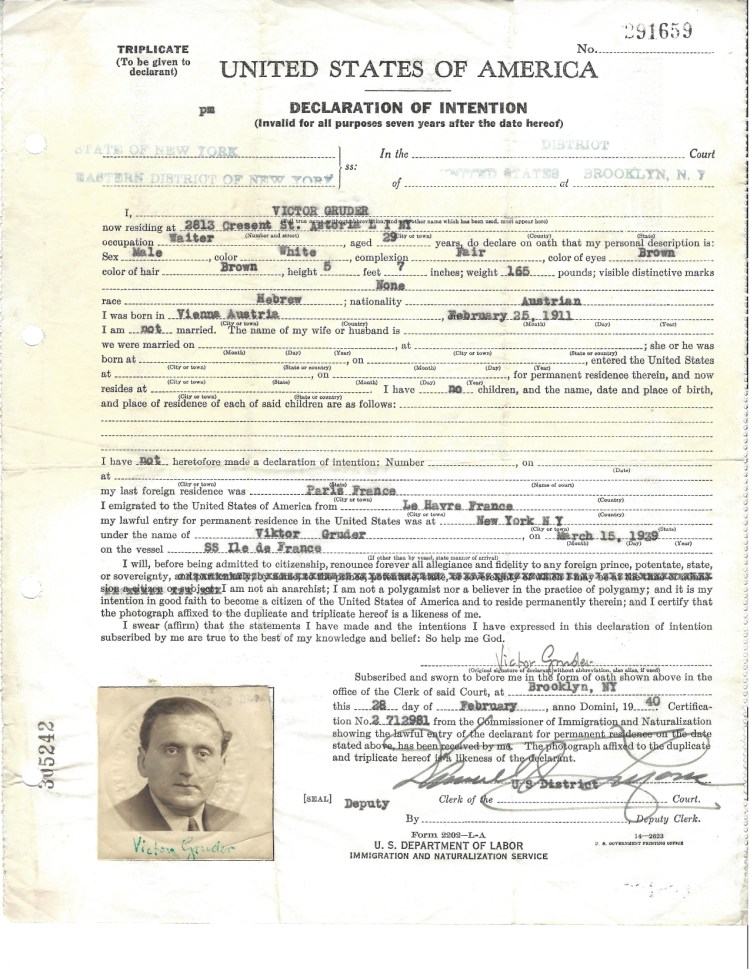

His parents chose to stay on in Paris for the foreseeable future – perhaps because Cicilia’s health was precarious. Following a benefit and farewell performance of “Mélodie Viennoise” in his honor on January 3, Viktor left Le Havre on 3 March, 1939 on the Ile de France and arrived in New York on March 14, 1939.

At a May Day rally in 1939 at the Austrian Socialist Club on 82nd St. E, Jeanette Schestopal recognized a newly-arrived and newly-respelled Victor Gruder whom she had encountered recently at the Jewish Agency. In conversation they realized they had already met in Paris in 1938, when so many were waiting for visas for the U.S. They took the same subway to Astoria.

While Vic came the U.S. with strong recommendations both from the hospitality sector and from expatriate Austrian political actors,

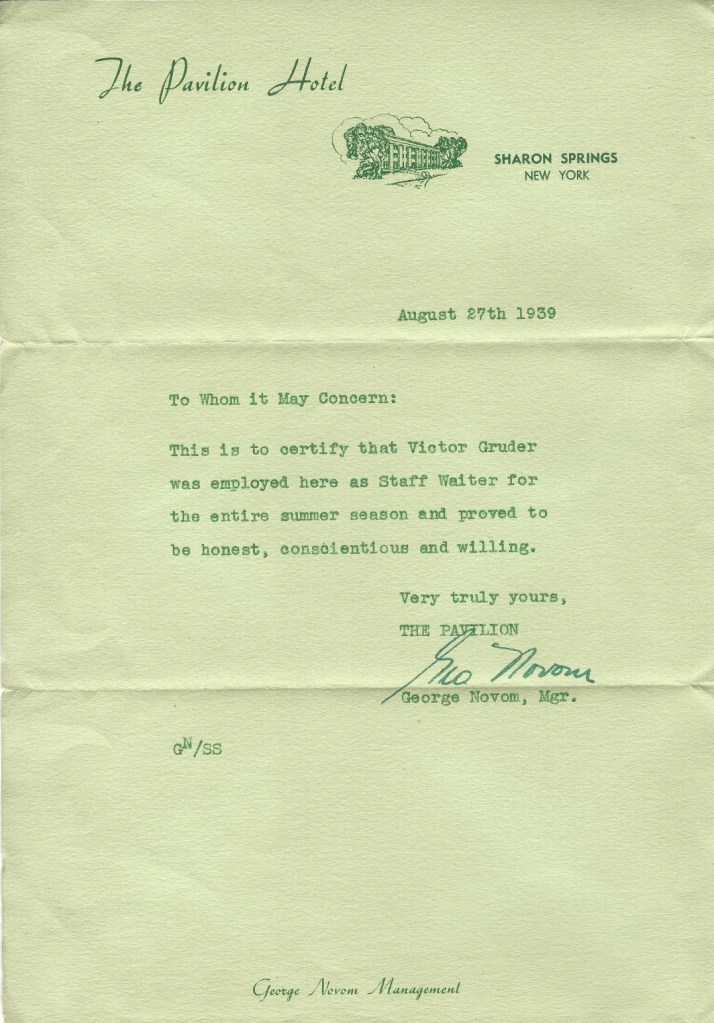

his English was poor, the country was in a depression, there were few jobs available, and he had no funds. Vic needed work. When Jeanette got a position at the Pavilion Hotel in Sharon Springs, NY, as a chambermaid, she helped him get a job as a waiter for children and staff at the same hotel and he was grateful for it.

The job Jeanette helped Vic get in Sharon Springs was the break he needed. While he started there as a “helps waiter,” he was quickly made a full waiter and he was able to secure later jobs on the basis of that experience.

He went on to the Hotel Cambridge in Florida and, during the winter of 1939/40, at the Hotel Grossman in Lakewood, NJ. Eventually, from 20 May 1941 to 10 September 1941, he was Head Waiter at The Brighton Hotel in Long Beach, LI.,

and then Ray Marden’s Riviera. At various times he also worked at the Hotel Savoy-Plaza, NYC, the Hotel Commodore, the Hotel Floridian, Miami Beach, and the Hotel Camden, Miami Beach.

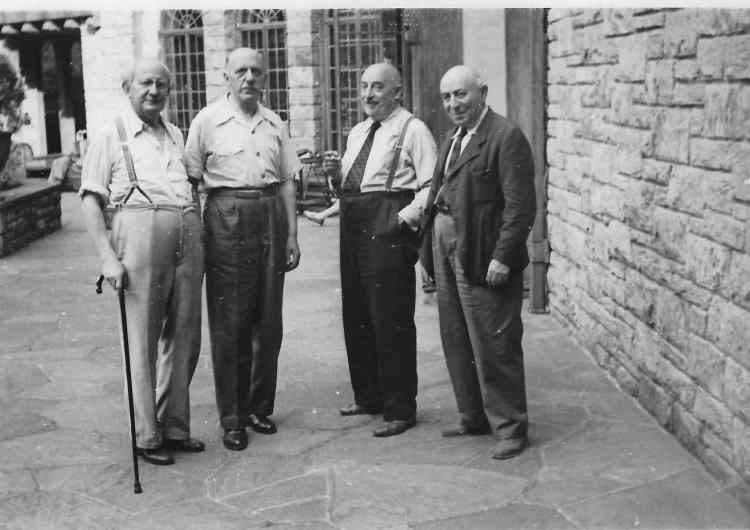

Cicilia, however, had died in Paris on New Year’s Eve 1939 of a heart attack. Not long after his wife’s death, Ignaz decided to move to unoccupied France — to Montauban, where many refugees were gathered. In very poor health and without any means of support, he was eventually interned there along with many other refugees. Ignaz did not reach New York City until 13 June 1941.

Happily, two weeks after Ignaz’s safe arrival in the U.S., Victor Gruder and Jeanette Schestopal were married by Jeanette’s aunt Gussie’s rabbi, Rabbi Joshua Goldberg of the Astoria Center of Israel. Together with Ignaz, they moved into a furnished apartment in a brownstone at 50 W. 94th St between Central Park West and Columbus Ave.

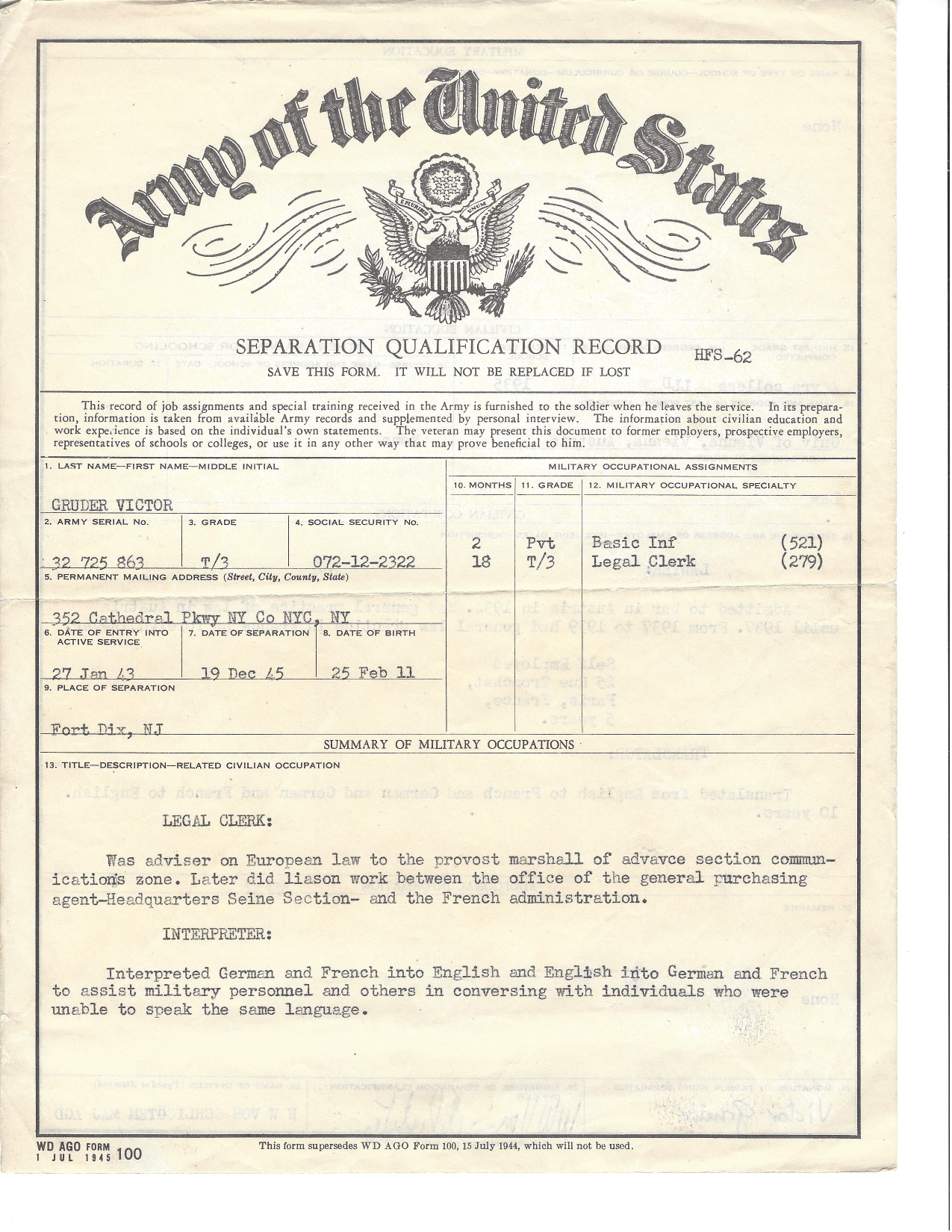

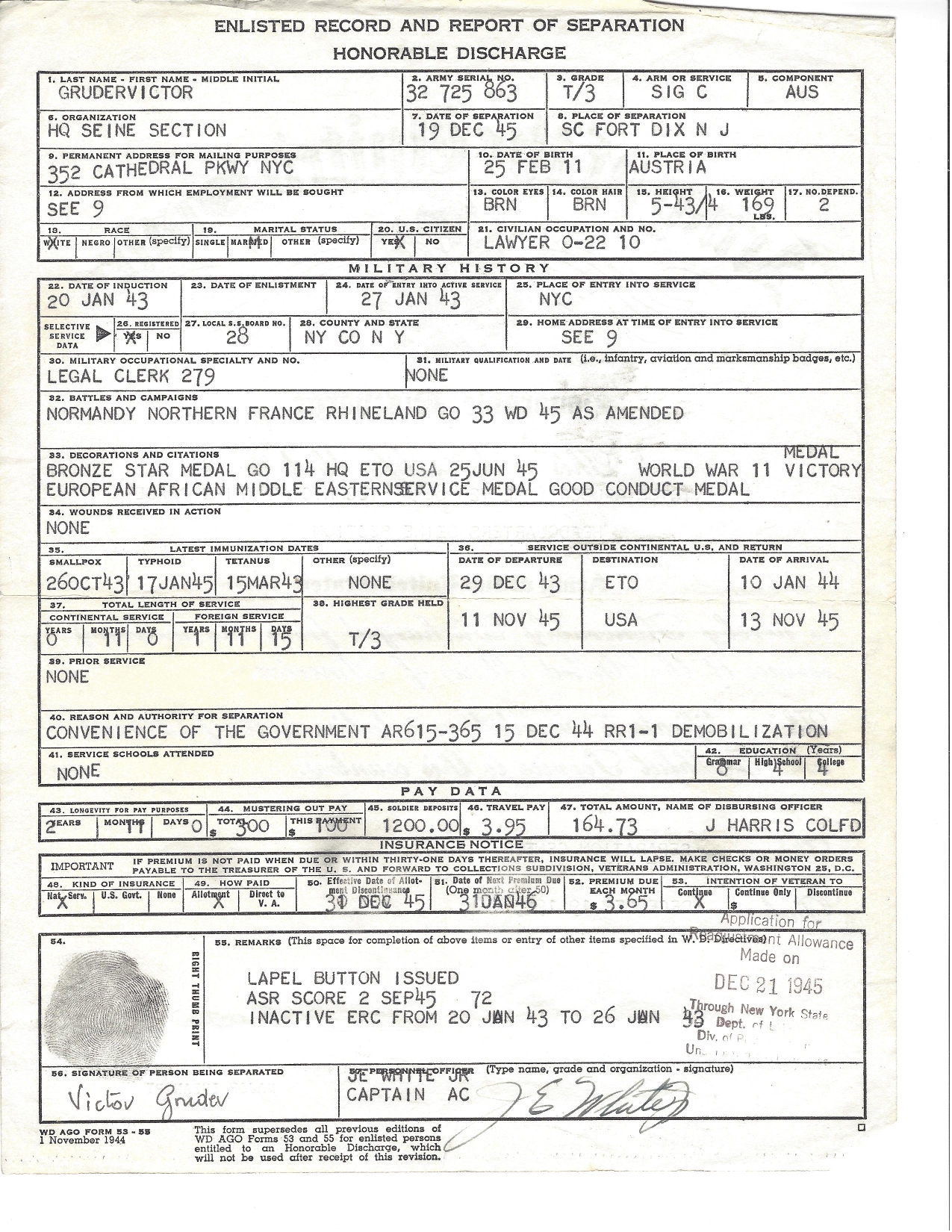

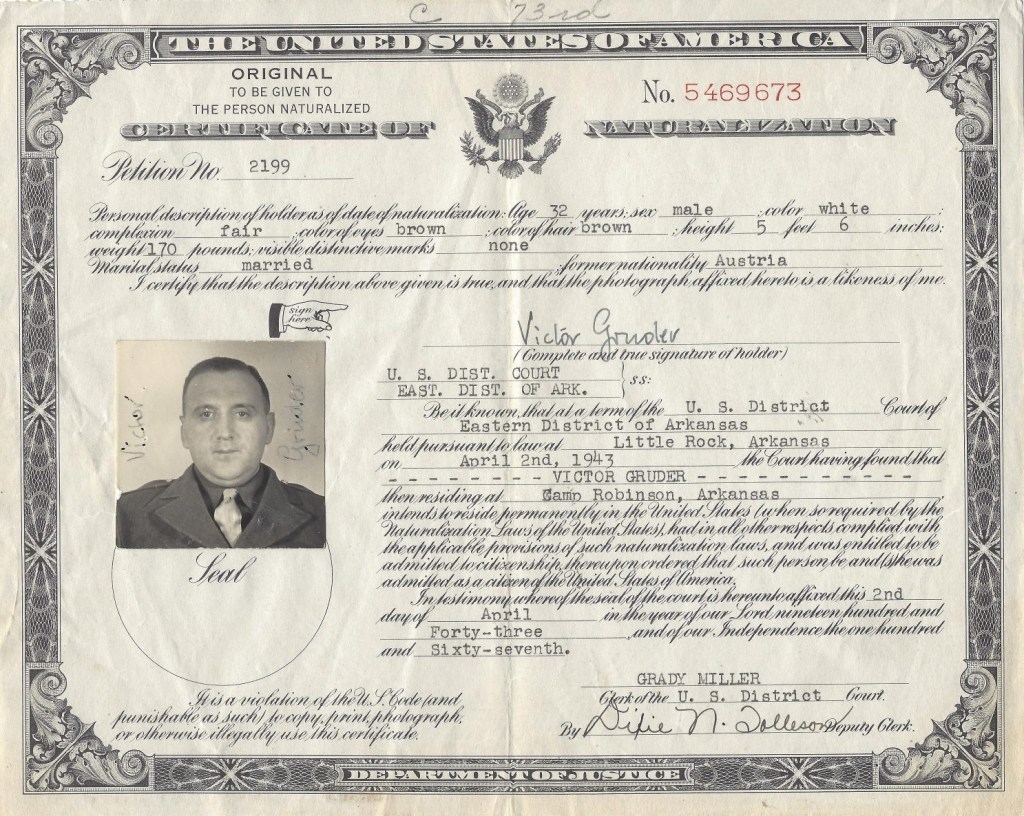

On January 27, 1942, wishing to participate in “our war,” Vic joined the U.S. army. He received accelerated citizenship on April 2, 1943, in Little Rock, Arkansas, during his basic training,

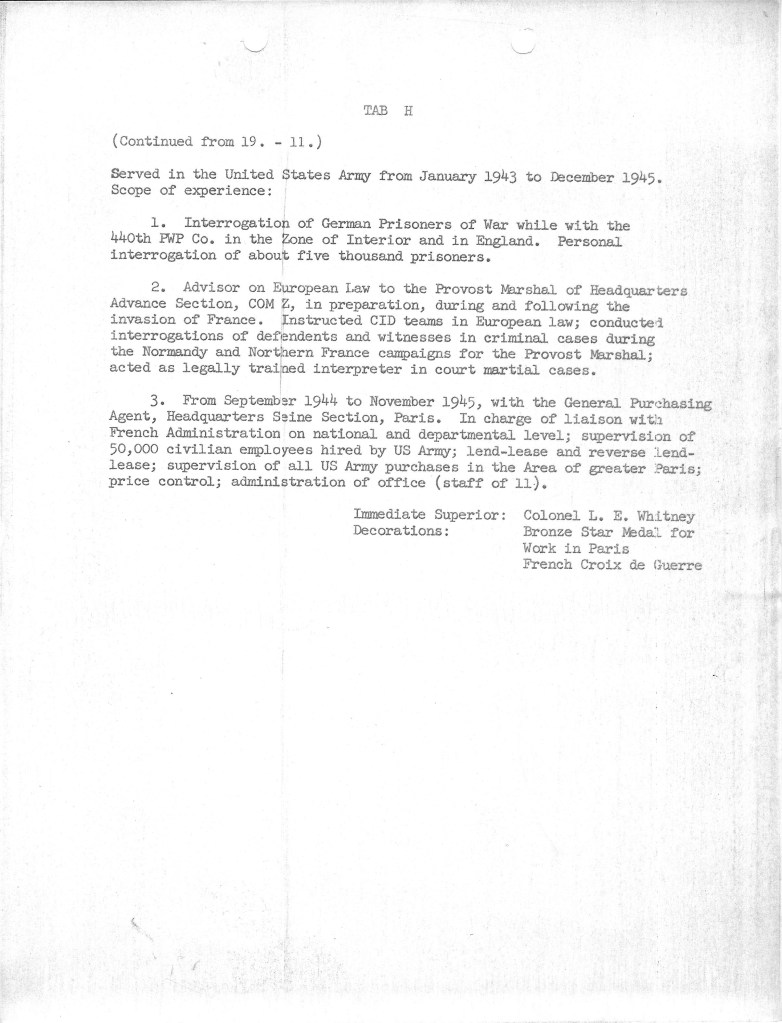

First assigned to the 101st Airborne, he eventually shipped out to France on 29 December, 1943 to work as a translator/advisor and legal clerk to the Provost Marshall of the advance section communications zone.

A Viennese Jew, you didn’t associate a Viennese Jew with anything but a coffeehouse and certainly not with the handling of a gun…

Victor Gruder, 1979

He landed with tens of thousands of other soldiers in Normandy on D + 3 Day. To a backdrop of artillery fire, he lived and worked in tents, processing German prisoners and translating for the negotiation of surrenders.

Eventually he was transferred to Paris to perform liaison work between the office of the general purchasing agent (Headquarters Seine Section) and the French administration.

For his performance in this assignment, Vic was awarded the Croix de Guerre avec étoile de bronze by the French government on 12 December 1945,

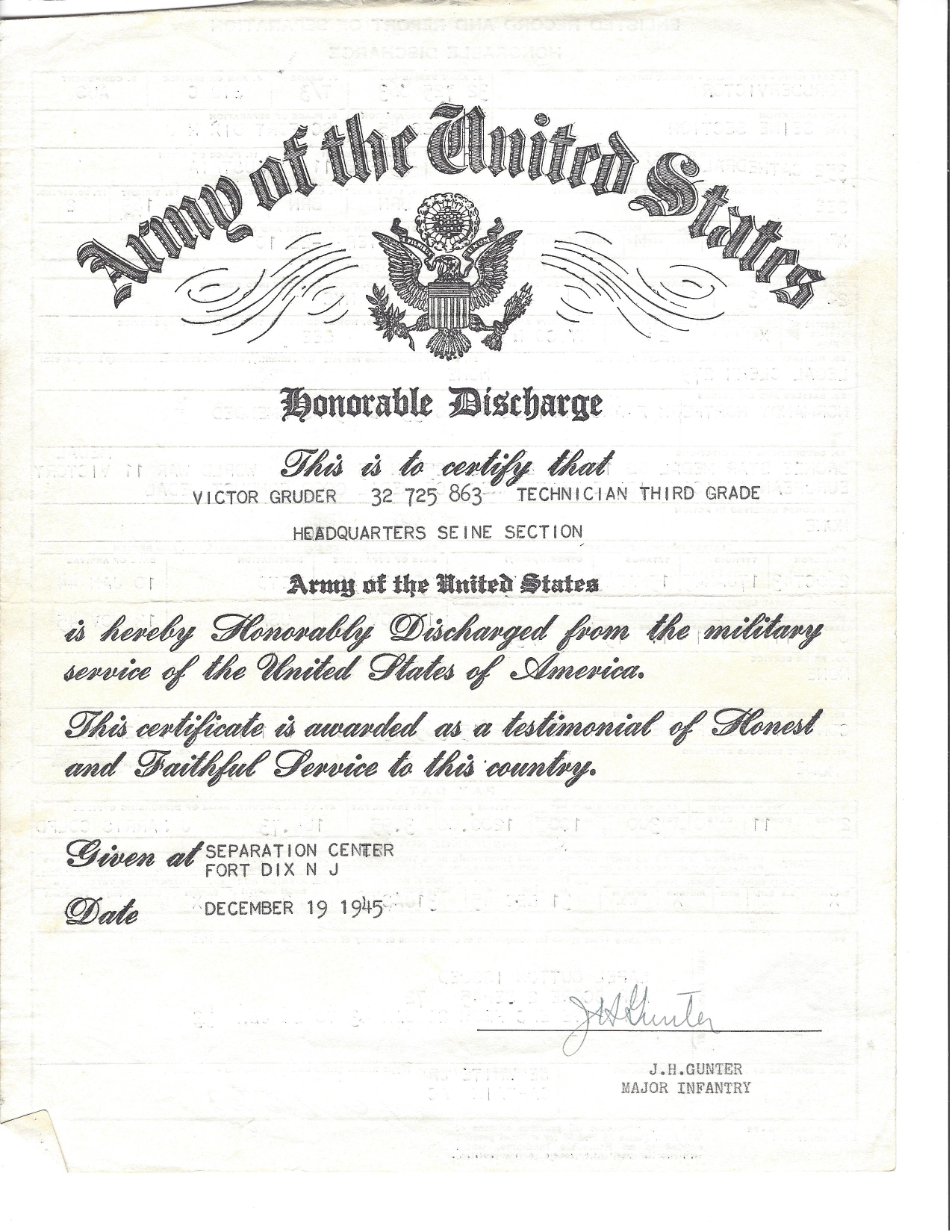

and the Bronze Star Medal for meritorious wartime service by the American Government. He was honorably discharged on 19 December 1945 at the rank of technician third grade (Staff Sergeant).